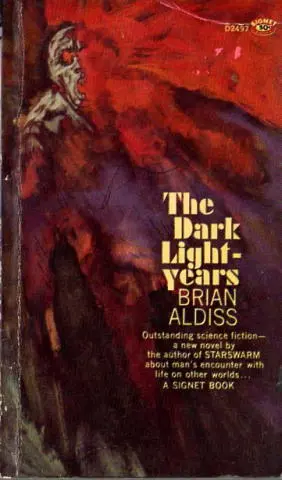

Brian Aldiss

THE DARK LIGHT YEARS

O dark dark dark.

They all go into the dark,

The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant,

The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters,

The generous patrons of art, the statesmen and the rulers….

T. S. ELIOT

On the ground, new blades of grass sprang up in chlorophyll coats. On the trees, tongues of green protruded from boughs and branches, wrapping them about — soon the place would look like an imbecile Earthchild’s attempt to draw Christmas trees — as spring again set spur to the growing things in the southern hemisphere of Dapdrof.

Not that nature was more amiable on Dapdrof than elsewhere. Even as she sent the warmer winds over the southern hemisphere, she was sousing most of the northern in an ice-bearing monsoon.

Propped on G-crutches, old Aylmer Ainson stood at his door, scratching his scalp very leisurely and staring at the budding trees. Even the slenderest outmost twig shook very little, for all that a stiffish breeze blew.

This leaden effect was caused by gravity; twigs, like everything else on Dapdrof. weighed three times as much as they did on Earth. Ainson was long accustomed to the phenomenon. His body had grown round-shouldered and hollow-chested accustoming him to it. His brain had grown a little round-shouldered in the process.

Fortunately he was not afflicted with the craving to re-capture the past that strikes down so many humans even before they reach middle age. The sight of infant green leaves woke in him only the vaguest nostalgia, roused in him only the faintest recollection that his childhood had been passed among foliage more responsive to April’s zephyrs — zephyrs, moreover, a hundred light years away. He was free to stand in the doorway and enjoy man’s richest luxury, a blank mind.

Idly, he watched Quequo. the female utod, as she trod between her salad beds and under the ammp trees to launch her body into the bolstering mud. The ammp trees were evergreen, unlike the rest of the trees in Ainson’s enclosure. Resting in the foliage on the crest of them were big four-winged white birds, which decided to take off as Ainson looked at them, fluttering up like immense butter-flies and splashing their shadows across the house as they passed.

But the house was already splashed with their shadows. Obeying the urge to create a work of art that visited them perhaps only once in a century, Ainson’s friends had broken the white of his walls with a scatterbrained scattering of silhouetted wings and bodies, urging upwards. The lively movement of this pattern seemed to make the low-eaved house rise against gravity; but that was appearance only, for this spring found the neoplastic rooftree sagging and the supporting walls considerably buckled at the knees.

This was the fortieth spring Ainson had seen flow across his patch of Dapdrof. Even the ripe stench from the middenstead now savoured only of home. As he breathed it in, his grorg or parasite-eater scratched his head for him; reaching up, Ainson returned the compliment and tickled the lizard-like creature’s cranium. He guessed what the grorg really wanted, but at that hour, with only one of the suns up, it was too chilly to join Snok Snok Karn and Quequo Kifful with their grorgs for a wallow in the mire.

“I’m cold standing out here. I am going inside to lie down,” he called to Snok Snok in the utodian tongue.

The young utod looked up and extended two of his limbs in a sign of understanding. That was gratifying. Even after forty years* study, Ainson found the utodian language full of conundrums. He had not been sure that he had not said. “The stream is cold and I am going inside to cook it.” Catching the right whistling inflected scream was not easy: he had only one sound orifice to Snok Snok’s eight. He swung his crutches and went in.

“His speech is growing less distinct than it was,” Quequo remarked. “We had difficulty enough teaching him to communicate. He is not an efficient mechanism, this manlegs. You may have noticed that he is moving more slowly than he did.”

“I had noticed it, Mother. He complains about it him-self. Increasingly he mentions this phenomenon he calls pain.”

“It is difficult to exchange ideas with Earthlegs because their vocabularies are so limited and their voice range minimal, but I gather from what he was trying to tell me the other night that if he were a utod he would now be almost a thousand years old.”

“Then we must expect he will soon evolve into the carrion stage.”

“That, I take it. is what the fungus on his skull signified by changing to white.”

This conversation was carried out in the utodian language, while Snok Snok lay back against the huge symmetrical bulk of his mother and soaked in the glorious ooze. Their grorgs climbed about them, licking and pouncing. The stench, encouraged by the sun’s mild shine, was gorgeous. Their droppings, released in the thin mud, supplied valuable oils which seeped into their hides, making them soft.

Snok Snok Karn was already a large utod, a strapping offspring of the dominant species of the lumbering world of Dapdrof. He was in fact adult now, although still neuter: and in his mind’s lazy eye he saw himself as a male for the next few decades anyhow. He could change sex when Dapdrof changed suns; for that event, the periodical entropic solar orbital disestablishment. Snok Snok was well prepared.

Most of his lengthy childhood had been taken up with disciplines preparing him for this event. Quequo had been very good on disciplines and on mindsuckle; secluded from the world as the two of them were here with Manlegs Ainson, she had given them all of her massive and maternal concentration.

Languidly, he deretracted a limb, scooped up a mass of slime and mud. and walloped it over his chest Then, re-collecting his manners, he hastily sloshed some of the mixture over his mother’s back.

“Mother, do you think Manlegs is preparing for esod?” Snok Snok asked, retracting the limb into the smooth wall of his flank. Manlegs was what they called Aylmer; esod was a convenient way of squeaking about entropic solar orbital disestablishmentism.

“It’s hard to tell, the language barrier being what it is,” Quequo said, blinking through mud. “We have tried to talk about it, but without much success. I must try again; we must both try. It would be a serious matter for him if he were not prepared — he could be suddenly converted into the carrion stage. But they must have the same sort of thing happening on the Manlegs planet.”

“It won’t be long now, Mother, will it?”

When she did not bother to answer, for the grorgs were trotting actively up and down her spine, Snok Snok lay and thought about that time, not far off now, when Dapdrof would leave its present sun, Saffron Smiler, for Yellow Scowler. That would be a hard period, and he would need to be male and fierce and tough. Then eventually would come Welcome White, the happy star, the sun beneath which he had been born (and which accounted for his lazy and sunny good nature); under Welcome White, he could afford to take on the cares and joys of motherhood, and rear and train a son just like himself.

Ah. but life was wonderful when you thought deeply about it. The facts of esod might seem prosaic to some, but to Snok Snok, though he was only a simple country boy (simply reared too, without any notions about joining the priesthood and sailing out into the star-realms), there was a glory about nature.

Even the sun’s warmth, that filled his eight-hundred-and-fifty pound bulk, held a poetry incapable of paraphrase. He heaved himself to one side and excreted into the midden, as a small tribute to his mother.

Читать дальше