Jensen Del Conte had seen more officers than he could possibly count in the course of his naval career. Some had been better than others, some had been worse; none had ever approached the abysmal depths which Elvis Santino plumbed so effortlessly. Del Conte knew Lieutenant Commander Hirake was aware of the problem, but there was very little that she could do about it, and one thing she absolutely could not do was to violate the ironclad etiquette and traditions of the Service by admitting to a noncommissioned officer, be he ever so senior, that his immediate superior was a complete and utter ass. The senior chief rather hoped that the lieutenant commander and the Skipper were giving Santino rope in hopes that he would manage to hang himself with it. But even if they were, that didn't offer much comfort to those unfortunate souls who found themselves serving under his immediate command – like one Senior Chief Del Conte.

Alcott continued her silent communion with her instruments, and Del Conte wished fervently that Santino's command chair were even a few meters further away from him than it was. Given its proximity, however, the lieutenant was entirely too likely to hear anything Del Conte might say to Alcott. In fact, the sensor tech was extremely fortunate that Santino hadn't already noticed her preoccupation. The lieutenant's pose of attentiveness fooled no one on the bridge, but it would have been just like him to emerge from his normal state of internal oblivion at precisely the wrong moment for Alcott. So far, he hadn't, however, and that posed a most uncomfortable dilemma for Del Conte.

The senior chief reached out and made a small adjustment on his panel, and his brow furrowed as his own display showed him a duplicate of the imagery on Alcott's. He saw immediately what had drawn her attention, although he wasn't at all certain that he would have spotted it himself without the enhancement she had already applied. Even now, the impeller signature was little more than a ghost, and the computers apparently did not share Alcott's own confidence that what she was seeing was really there. They insisted on marking the icon with the rapidly strobing amber circle which indicated a merely possible contact, and that was usually a bad sign. But Alcott possessed the trained instinct which the computers lacked, and Del Conte was privately certain that what she had was a genuine contact.

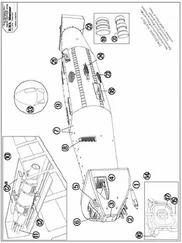

Part of the problem was the unknown's angle of approach. Whatever it was, it was overtaking from astern and very high – so high, in fact, that the upper band of War Maiden's impeller wedge was between the contact and Alcott's gravitic sensors. In theory, CIC's computers knew the exact strength of the heavy cruiser's wedge and, equipped with that knowledge, could compensate for the wedge's distorting effect. In theory. In real life, however, the wedge injected a high degree of uncertainty into any direct observation through it, which was why warships tended to rely so much more heavily on the sensor arrays mounted on their fore and aft hammerheads and on their broadsides, where their wedges did not interfere. They also carried ventral and dorsal arrays, of course, but those systems were universally regarded – with reason – as little more than precautionary afterthoughts under most circumstances. In this case, however, the dorsal arrays were the only ones that could possibly see Alcott's possible contact. The known unreliability of those arrays, coupled with the extreme faintness of the signature that had leaked through the wedge, meant that the contact (if that was what it actually was) had not yet crossed the threshold of CIC's automatic filters, so no one in CIC was so far even aware of it.

But Alcott was, and now – for his sins—Del Conte was, as well. Standing orders for such a contingency were clear, and Alcott, unfortunately, had followed them . . . mostly. She had, in fact, done precisely what she would have been expected to do if she had still been part of Lieutenant Commander Hirake's watch section, for the lieutenant commander trusted her people's abilities and expected them to routinely route their observations directly to her own plot if they picked up anything they thought she should know about. Standard operating procedure required a verbal announcement, as well, but Hirake preferred for her sensor techs to get on with refining questionable data rather than waste time reporting that they didn't yet know what it was they didn't know.

Del Conte's problem was that the lieutenant commander's attitude was that of a confident, competent officer who respected her people and their own skills. Which would have been fine, had anyone but Elvis Santino had the watch. Because what Alcott had done was exactly what Lieutenant Commander Hirake would have wanted; she had thrown her own imagery directly onto Santino's Number Two Plot . . . and the self-absorbed jackass hadn't even noticed!

Had the contact been strong enough for CIC to consider it reliable, they would already have reported it, and Santino would have known it was there. Had Alcott made a verbal report, he would have known. Had he bothered to spend just a little more effort on watching his own displays and a little less effort on projecting the proper HD-image of the Complete Naval Officer, he would have known. But none of those things had happened, and so he didn't have a clue. But when CIC did get around to upgrading their classification from sensor ghost to possible real contact, even Santino was likely to notice from the time chop on the imagery blinking unnoticed (at the moment) on his plot that Alcott had identified it as such several minutes earlier. More to the point, he would realize that when Captain Bachfisch and Commander Layson got around to reviewing the bridge log, they would realize that he ought to have been aware of the contact long before he actually got around to reporting it to them . Given Santino's nature, the consequences for Alcott would be totally predictable, and wasn't it a hell of a note that a senior chief in His Majesty's Navy found himself sitting here sweating bullets trying to figure out how to protect a highly talented and capable rating from the spiteful retaliation of a completely untalented and remarkably stupid officer?

None of which did anything to lessen Del Conte's dilemma. Whatever else happened, he couldn't let the delay drag out any further without making things still worse, and so he drew a deep breath.

"Sir," he announced in his most respectful voice, "we have a possible unidentified impeller contact closing from one-six-five by one-one-five."

"What?" Santino shook himself. For an instant, he looked completely blank, and then his eyes dropped to the repeater plot deployed from the base of his command chair and he stiffened.

"Why didn't CIC report this?" he snapped, and Del Conte suppressed an almost overwhelming urge to answer in terms which would leave even Santino in no doubt of the senior chief's opinion of him.

"It's still very faint, Sir," he said instead. "If not for Alcott's enhancement, we'd never have noticed it. I'm sure it's just lost in CIC's filters until it gains a little more signal strength."

He made his voice as crisp and professional as possible, praying all the while that Santino would be too preoccupied with the potential contact to notice the time chop on his plot and realize how long had passed before its existence had been drawn to his attention.

For the moment, at least, God appeared to be listening. Santino was too busy glaring at the strobing contact to worry about anything else, and Del Conte breathed a sigh of relief.

Of premature relief, as it turned out.

Elvis Santino looked down at the plot icon in something very like panic. He was only too well aware that the Captain and that asshole Layson were both out to get him. Had he been even a little less well connected within the aristocratic cliques of the Navy, Layson's no doubt scathing endorsement of his personnel file which had almost certainly accompanied the notation that he had been relieved as OCTO for cause would have been the kiss of death. As it was, he and his family were owed sufficient favors that his career would probably survive without serious damage. But there were limits even to the powers of patronage, and he dared not give the bastards any additional ammunition.

Читать дальше