‘Yeah, that’s great,’ said Carl, dropping out of the bottom of the Flying Fox; ‘but I don’t know if we’re going anywhere in this thing.’

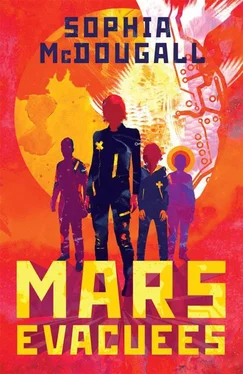

I’d actually been avoiding looking at the spaceship, and I think Noel and Josephine had been too. It was fairly easy to do when there were people shaking and bleeding and a dead Space Locust there to concentrate on. But it turns out when Space Locusts eat holes in your spaceship, the spaceship does not like it very much.

The Flying Fox was riddled with holes, and there were important-looking cables that had been chewed through sticking out of it all over the place, and it was giving off an unhappy singed smell.

Carl went in and poked some buttons on the dashboard, and the ship whirred miserably and its lights flickered for a second before going out again.

‘Carl, are we… stuck?’ asked Noel. And being a bright but not particularly optimistic kid, he put the rest of it together pretty fast. ‘Are we going to run out of oxygen and die?’

‘We’re fine, Noel,’ said Carl grimly. ‘We’re going to be fine.’

‘But what are we going to do?’ asked Noel.

‘ Math !’ blurted the Goldfish, but then it shook itself and said, ‘I have some tutorials on spaceship repair.’

So the Goldfish projected plans and talked us through the things that needed to be welded together and the leaks that needed to be plugged. Our problems were twofold. Firstly, the people who made the tutorials had never really thought about being partially eaten by flying worms as a condition a spaceship might get into. Secondly, I soon got the idea that the main principle for learning spaceship repair is: don’t be crashed miles from anywhere on the surface of Mars when you need to do it.

Still, we stuck everything back together that we could and Josephine worked out how to re-route the power around the broken bits, I guess, and the lights came on. Then Carl jiggled the controls around for about a thousand years and eventually worked out that you now had to hold the control yoke at a special angle, and we finally got back into the sky. We all cheered and the Goldfish covered us in sparkles. There is a limit to how pleased you can honestly feel about having to go flying in a ship that now resembles a colander more than anything else, but you have to take what you can get.

But sure enough, about an hour later, smoke started wafting gently out of the panelling. And then we were heading for the ground at a few hundred miles an hour, out of control and on fire.

Valleys gouged between jagged red rock walls blurred underneath us at a nasty angle. Carl wrenched at the controls, which had stopped working altogether, and yelled, ‘ Somebody hold it .’ I crawled underneath the yoke and tried to hold it solidly at the special position so he could actually steer.

We came within a second of flying straight into a cliff face. Somehow we hit the valley floor instead. Bounced with an awful noise of crunching metal. Skidded. Stopped.

We sat there for a while hyperventilating and not looking at each other. Then, when we didn’t really have an excuse for not doing it any more, we got out to look at the damage.

It was awful. There was a trail of blackened bits of Flying Fox strewn back along the valley and the ship was lying tilted over, propped on one fin, and even at a glance you could see three of its thrusters were crumpled like used crisp packets.

‘How far are we from Zond, Goldfish?’ I asked.

‘Oh, I make it one thousand, three hundred and twenty-seven miles, Alice,’ the Goldfish said.

There didn’t seem to be much to say about that. ‘We’d better get started,’ I said. And we got out our meagre collection of tools and began again.

The thing about trying to fix plasma compression engines with a staple gun, duct tape and highlighter pens is: you can’t.

We kept trying, though. For hours. Even when the light faded and our fingers went numb, and we got weak and dizzy from the low-oxygen air and had to keep topping our canisters up from the ship’s supply. At least that was still working.

‘How long will that last?’ I asked the Goldfish airily, as though the answer wasn’t particularly important.

‘Five days, three hours, forty-seven minutes. Give or take,’ the Goldfish replied.

I kept on trying to work out if the three chunks of twisted metal in my lap could be made to resemble an inertial compensator if I applied enough superglue.

‘Those things are still out there,’ muttered Noel.

We looked at the sky. There didn’t seem to be any Space Locusts in it, but we’d seen how fast they could move.

There didn’t seem to be much to say about that either.

Eventually Carl said in a weird, forced, cheerful voice that didn’t sound like him at all: ‘Guess there’s nothing more we can do tonight! Let’s get some rest while we can. We’ll get straight back to it, come first light.’

There was a big hole in the tent and none of us had the heart to try and get it set up anyway, so we just packed together for warmth into an unhappy pile of people at the bottom of the spaceship and tried to sleep.

I dreamed Mum flew down into the valley in her Flarehawk and said she’d been looking for us for ages. It seemed so real that though I woke up a lot of times during the night, I found that I could shut my eyes and go on dreaming that we were on our way back to Earth and then landing on a sunny base somewhere in Africa, and Josephine was showing some military scientists the Space Locust, and Dad was there and we were drinking tea while I told them about everything that had happened…

(I didn’t go as far as dreaming the war was over and everything was completely fine. I guess that would have seemed too unrealistic and I’d have woken up.)

But eventually I did have to wake up properly, because something was making a pounding noise, sharp and ringing like someone hammering metal, annoyingly close.

‘Whassat,’ I groaned into a grubby fold of Space-Locust-chewed sleeping bag.

‘That’s Carl,’ said Josephine dully. I sat up and looked at her. She was sitting in the pilot’s seat, motionless. She somehow looked as if she’d been there a long time and I wondered if she’d slept at all. ‘He’s been doing it for hours.’

I went outside to look. It was barely light. The two little moons were still pale in the sky, and the valley was striped with weird shadows from the columns of twisted rock that stood along its walls. Carl was kneeling on the ground, using a flat rock as an anvil and trying to bang some part of the engine back into shape with a stone.

‘Are any of you going to help, or what?’ he exploded as soon as he realised I was watching.

Josephine appeared at my side, soundless as a ghost. ‘It’s hopeless, Carl,’ she said softly.

Carl let out a strangled yell and hurled the bit of engine at the rock wall with all his strength so it bounced off with a noise like SPANG and the echoes clattered around the valley. Carl swiped one hand across his eyes. Then he turned round and said so brightly he sounded almost like the Goldfish, ‘OK! So we’re going to have to get rescued.’

Josephine put her oxygen mask on and quietly wandered away along the valley. I don’t think Carl paid much attention. It wasn’t Josephine he was talking to. He was talking to Noel, even though he couldn’t quite look at him; Noel, who was sitting on the edge of the Flying Fox’s wing, very still and huge-eyed and quiet. Carl went and pushed him off and wrestled with him a bit in a pointedly brotherly way. ‘Kind of embarrassing. We’re never going to hear the end of it when we get home.’ His voice was even louder than usual. ‘What we need to do is work out how to get attention. There’s probably a mirror somewhere in the ship we can use, to flash in Morse code or something.’

Читать дальше