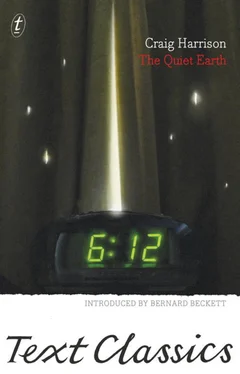

The dominant colours are greens and reds. They are all outdoor photos. The greens shade from the bright emerald tones of tropical plants, leaves, and grass, to the dull khaki of soldiers’ uniforms. The reds are the meat and blood of pieces of human bodies. At first it is hard to see what is there. And then it is suddenly clear. The amputated parts of shattered human beings have been collected for the photographer. The victims are presumably Vietnamese; one soldier is holding up by the hair a severed head connected to part of a shoulder and an arm, and the head is Asian, slightly bloated, an eye missing, but the face of a youth of about sixteen. It is hard to guess. Another photo shows the remnants of a man whose penis has been removed. He is naked, sprawled like a shop window doll, very pale on stained dark grass and reddish-brown earth. There is a photograph of a pattern of parts of bodies set out on dark earth. All the photographs include glimpses of the soldiers standing around. A fair-haired man in a khaki singlet features in two pictures. The last photo shows a large heap of mutilated bodies; above them, two men looking at the camera, arms resting on each other’s shoulders. The man on the right is grinning, his white teeth the only feature visible beneath the shade of a forage cap. Both men are dressed in combat gear, and both seem to be Maoris. The one on the left, who has tipped his helmet back rakishly so that the sun on his face is making him squint, is Apirana Maketu.

The easiest way to kill him would be with sleeping pills in a drink. He will not suspect anything. I have left everything exactly as it was. So I have the advantage.

How dangerous is he? He seems fairly normal, but I know that can be deceptive. The retching sensation rises in the back of my throat again. I hold it in, swallowing hard. I am in the dining room, seated, holding the arms of the chair.

I must remember what he said, try to think back. He said, they wanted to make him obey orders, to pull the trigger, to kill. Then later, he said, that Sunday, nobody would admit—or was it, nobody would believe—the answer, if you asked, have you killed people? And he asked if he was evil. I remember that. And then tried to dodge, turned it all around, aimed it back at me.

He hid from me about how long he’d been in the army. In war, yes, they’d obey orders. Shoot. There were no clear battlelines. I know that much. But what’s that got to do with those…obscenities? What would make them do that ? And pose themselves in pictures of it? Who would keep such things?

What if he wanted me to find them? He could have locked them away somewhere, more secure. I might have done exactly what he expected me to do. He wanted to confess all along. But he couldn’t. No, that doesn’t make sense. But insane people don’t make sense.

I get up and open the top windows. The air is humid, unmoving. A white haze hides the distance. The hills look like piles of waste by a pool.

Before, the land had threatened or unsettled me by its nothingness, it had seemed to want to suck living and moving identities dry of life and absorb them into the vacuum. Now I can sense a more active vibration emanating very faintly from beyond the temporary structures of these rooms and blocks. As if it had detected after a huge spread of time spent silent and waiting, a hint, finally, of complete triumph; and now it was daring to stir itself for the kill. Softly, like a thing furred with decay, something immensely ancient becomes intent and flexes its death-energy. It has been there forever. The Maoris must have absorbed it for ages without fully knowing, like inhaling the spores of a mould or a bone-marrowing radiation. Those carvings, the masks of faces howling outwards from their shelters, must have been meant to repel it. Or to want to throw it out, like vomit. That braying sound I thought I heard by Taupo as the sun went down the night before I met the Maori, that might have been its signal. It wanted an answer, an echo from the base of our brains. It knows what is inside.

I stand there, firm against it, my mind forcing back the hostile resonance. The rancour is almost a perceptible taste. It will be cheated of me. It will not win.

A screech of noise echoes round the towers like an animal trapped in machinery. My heart stops, in shock, then pounds away at double speed.

There is a shout. I look down from an open window. The figure is standing by a bright red car, waving and sounding the klaxon horn.

‘Come on down!’

I get the shotgun. At the top of the stairs I stand and pause, taking deep breaths. I must keep control.

Below, he is leaning on the car, excited, one arm extended across the roof above the windscreen, the owner embracing his new toy. Posing for a photograph. The images blur in front of me.

‘Well?’ he asks.

‘Where did you go?’ is all I can say.

‘Motorway to Porirua and back, then on the Hutt motorway.’ He seems impatient, and taps the top of the windscreen. ‘See anything?’

‘What?’

‘Look.’ He points. I move closer, puzzled. The windscreen slopes back, reflecting a distorted stretch of the concrete block and the white sky. A long smear extends up the centre of the glass on the outer surface. I lean over, glancing at him. He is on the other side of the car, nodding, eyes very bright.

The smear is what is left of a disintegrated fly or wasp obliterated at high speed, a blotch of pulpy yellow pus and dark red blood flecked with bits of black. I draw in breath, my teeth and lips clenched tight.

‘A fly,’ he says, triumphantly. I straighten up. The butcher’s red of the car burns into my retina. ‘It means they’re still around,’ he goes on. ‘You know what you said.’

‘It means you killed an insect,’ I reply.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘It doesn’t make sense.’

‘Why not?’

‘Just one? After three weeks?’

‘There’ll be others. I mean—’ He stops.

‘There would have been more. The rate they breed.’

‘We might not have seen them.’

‘We’d have seen them all right.’

‘It was when I was coming back, along the motorway, just now.’ He turns, points, and turns back. Then, uncertain, the excitement gone, he stares at me. ‘Well what does it mean, then?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You must bloody know. You said, when we—you must bloody well know.’

‘I said if there were any left, they’d breed if they weren’t sterile.’ He closes his eyes, suddenly, and bangs his hand on the roof of the car. ‘Maybe there was only one left. And you killed it. Or maybe—’

‘Maybe what?’

‘Somebody’s playing a joke.’

He opens his eyes.

‘Oh, for Christ’s sake!’ There must be something about my manner which for the first time, as his excitement subsides, strikes him as different. He detects a change.

‘What’s wrong with you?’ he says. ‘Anything happen, while I was—’

‘I don’t feel so good today. That’s all.’

‘How? How d’you feel?’

‘It’s nothing.’

‘Oh, come on, man, if you get sick—’

‘It’s just a…stomach ache.’

‘Bad?’

‘No. It’s okay.’

‘We both ate the same stuff. I’m okay. You didn’t drink any water?’

‘No.’ I move back towards the hotel. ‘I’ll just take it easy for a while.’

He stands by the elegant machine with the death-mark smeared down its face. Brave soldier. You expect a medal?

‘I’ll clean it off then,’ he says. A pause. ‘There’ll be others. They’ll start to come back.’

I turn, holding the glass door, and look at him. Not very long ago I would have taken a scientific view of the phenomenon. Now the structure of objects which compose this scene and have blended into the making of this event seem malevolently organised. I have been too naïve.

Читать дальше

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/books/28041/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island-zero-thumb.webp)