He leans against the doorjamb, his arms folded, holding a black book. We are about to go upstairs and make breakfast. No eggs, no bread, no milk. I am tying my shoelaces.

‘They put these in all the rooms.’ He waves the Gideon Bible. ‘I was thinking about, er…you know.’

‘About what?’

‘Aw… I thought I might go to, you know, to a church.’

I stop and look up at him.

‘Oh.’

‘Couldn’t do any harm, eh?’

‘Or good.’ My head is down again.

‘What?’ A pause. ‘You never know.’

‘What will you do?’ I ask.

‘Well… sort of… pray, I s’pose. Dunno really. I just thought…’ He sighs, looks at the cover of the Bible, embarrassed. ‘We were always bein’ packed off to church when we were kids. It gets to you after a while. ‘Course, it’s years since I went.’

I stand up.

‘What did you do last Sunday?’

‘There’s a church at Waiouru. I went in for a while.’

‘You don’t have to go to a church to pray, do you?’

‘No. S’pose not. Seems right, though.’

‘I don’t have any religious beliefs.’ I say this rather formally, uncertain about the areas we are moving into.

There is a pause; then he says, ‘We were Methodists.’

‘Well… if you want to, then…’ and I shrug.

We go out of the room into the corridor, and begin to climb the stairs to the dining room. He brings his Sten gun, holding it pointing down. He climbs in silence.

‘What will you pray for?’ I ask, momentarily reckless, as we enter the dining room and see the early morning sun streaming in on the littered plates and empty bottles from the evening meal; ‘that everyone will come back?’

He glances at me with a slightly puzzled expression.

‘That nothing bad’s going to happen. That it’ll all work out. And… we’ll be… you know, okay. We’ll be saved.’

I stare out at the bright day, the silence rampant like a dead animal on heat, the harbour water flaring into an incendiary light pinching my eyelids almost shut. He speaks casually as he clears the table, stuffing bottles and remnants into a metal waste bin. The word ‘saved’ has no special inflection. Should it have? What does it mean? When he says it, what image in his mind does it connect to?

It had not occurred to me that we might be ‘saved’. I thought we already had been.

Having agreed that we should stay fairly close together, I have to accompany him in his search for a church. The idea that Sunday is a special day does exert a curious pressure, powerfully reinforced by the deserted streets and closed shops. It seems hard to avoid talking in whispers.

But the expedition becomes farcical. The first church is Roman Catholic, and Apirana tells me to drive on. We are in my car with the windows rolled down. The sun is hot. He is wearing dark trousers, black shoes and a white shirt. I presume this is part of his civilian clothing. His sleeves are rolled up to reveal a tattoo on his left forearm. He props his left arm out of the car window and keeps tapping the outside of the roof or door with his fingers, betraying irritation, probably wishing he’d never suggested this expedition, wanting to find a church and get the ludicrous business over and done with. I hide behind dark glasses and an indifferent expression, as neutral as possible, easy for me to maintain. But he misinterprets this. It adds to his irritation.

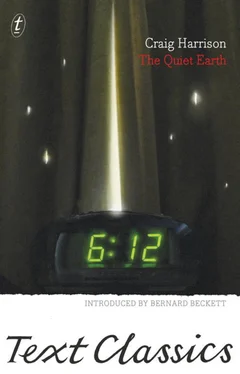

We locate an Anglican church and he decides it will do. I wait in the car. He gets out and goes up the steps. Of course the doors are locked. It is still really 6.12 am on a Saturday. He comes back, sweating, gets in the car, slams the door.

‘Could break in, but it wouldn’t be right,’ he says.

‘If you like,’ I suggest tonelessly, ‘I’ll break in. It’s all the same to me.’

He goes tight-lipped. I try to think of some way I can safely disarm any vague religious notions he might have about what has happened. They can only be dangerous. He is already very tense. I suppose Bibles have a bad effect on weak-minded people. And churches act like echo chambers on psychotics.

‘Never mind,’ he snaps; ‘doesn’t matter.’

I swing the car into a wide turn and drive aimlessly along Willis Street and down the canyon of Lambton Quay. He lapses into a sullen silence. A lolling, spastic idiocy seems to have invaded the space between us. It is hard to know how strong it might be. My hands go clammy on the rim of the wheel. We are the only people left in the world. Every other living thing has gone as if nothing more than the images of a film bleached out of existence, wiped from a screen by a burst of light in complete silence; evaporated like bits of tissue in a furnace. And here we are. Not talking to each other.

What should I do? Apologise, sympathise? That would only pander to the absurdity. He started this. Does he need to be given a way out?

I stop the car in the shade; flick the key to kill the engine.

‘This is stupid,’ I say. He shrugs. There is a long silence. Suddenly he asks if I believe in anything. He says it sarcastically. I reply that I haven’t had the kind of life which would keep me believing in very much.

‘Maybe you should think about it,’ he says.

Now I can use some righteous indignation on him.

‘Don’t you think I have ?’

‘You’re not the only one who’s had a bad time.’

‘I know that. But you asked me , so I’m telling you.’

He looks at me.

‘You haven’t told me anything.’

He’s right. I don’t want him to know too much. I remember the Maori boy years ago outside the house in Herne Bay and how he seemed to be able to make such dangerous and accurate deductions about people who were total strangers. But now, if I’m careful, in control, I can select what to tell. Otherwise he might wonder why I should want to conceal everything.

So we sit there in the car, and I look ahead at the empty street from behind my dark glasses, my hands resting on the steering wheel; and the Maori props his back against the far door and stares at me; and I tell him about Peter and Joanne, and how one evening whilst I was answering the telephone and getting towels from the airing cupboard the child had drowned in the bath. I tell him as much as I think necessary. He presents an impassive, sombre expression. Perhaps there is a morbidity in him which needs feeding, or needs the consolation of finding a lot of disorder inside what must appear to them to be our peculiarly tidy lives. Or it could be part of the Polynesian obsession with death. That must have been what hypnotised them with Christianity. Mysticism, sacrifice, cruelty; sporadic self-pity disguised as compassion: yes, it appealed to them. Worst of all, the insistence on guilt. A tumour in minds, a whining to be forgiven or made miserable. Obscene that this should persist when people had so much power over their own lives. It must make them always expect the worst. And get it.

When I stop, damp with sweat, he says nothing. I turn and face him blankly. He looks down. Then he speaks, quietly: ‘You say you don’t go for religion. But you believe in evil. You saw that animal on the road. Or whatever it was. You said it was evil.’

‘Yes.’

‘What did you mean, then?’

‘It was something which would…destroy life. For no reason. Something which thrives on destroying life.’

‘Having a reason makes a difference, you reckon?’

I lean on the steering wheel and sigh.

‘Oh, I can’t argue round all that. We’d be at it for weeks.’

‘Well,’ he says slowly, ‘I’m a soldier. It’s my job to go out and kill people, if I get the word. Just orders. They don’t give reasons . So am I evil?’

I feel an itching like static electricity inside my spine.

Читать дальше

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/books/28041/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island-zero-thumb.webp)