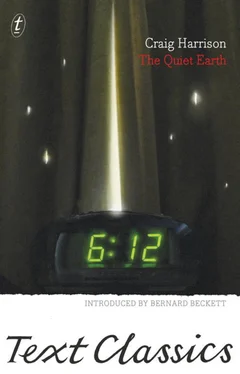

Obviously the world had undergone a psychic jolt; the Maori had confirmed that a change had occurred. The world we were in was almost exactly, but not quite, the same as the old world. A subtle dislocation somehow involving the processes of perception had shaken the normal boundaries out of place. It was hard to detect, like a familiar room in which something is very slightly changed. And it induced the same unease.

I had no concepts or words to apply to this. I had to struggle with the realisation, also, that I wasn’t unique, I wasn’t the focal point, I hadn’t been especially chosen for some revelation or saved for a purpose. The universe was simply careless. Its disorder seemed to me to be a betrayal. The calm I had felt earlier was eaten up within me by a cancerous rage. The universe was simply careless. After the silent bang, there remained a few pathetic whimpers. I was one. Asleep in the next room was another, making occasional sounds very like pathetic whimpers.

Perhaps that was how I slept, too.

* * *

In some dreams I see photographs of my family which were never taken. They show Joanne and myself, and Peter as a normal child, with such clarity that even as the dream is going on I wonder if this is a future which does exist somewhere in the universe. We are on a boat, a ferry, in what seems to be the Bay of Islands, leaning on a white-painted rail, laughing. Another shows Peter reading a magazine on a beach. He is slightly older than he ever was; about twelve or thirteen.

Then, sometimes, there are events from that alternative world, in which these people move and talk. I am taking a piece of meat from a barbecue grill and putting it on a plate held by Peter; he makes a face and complains that the steak is burnt, and Joanne laughs and asks why I insist on cooking outdoors but hardly ever in the kitchen. Peter groans and says, Mum, for heaven’s sake, don’t encourage him. Then there are other segments of clearly defined events, frighteningly vivid. It worries me that they should have such clarity. None of them are significant, they lack any specific meaning, their ordinariness is equally disturbing. We move through rooms which must exist in the real world somewhere, and from which we could not be subtracted without violating the rules of the universe, without creating an absence and a vacuum as impossible as that which I had felt in the succession of empty houses I had entered all through the afternoon at Thames. And yet now we are not there; the impossible has happened twice. I move through an empty room towards a mirror. When I stand in front of it, and look into it, I cannot see myself. There is nothing.

* * *

The road wound down and around awkwardly and then came up, turned, and pointed straight across the desert plateau. The day was cloudless, the sky acid-blue behind the snow on the tops and slopes of the mountain volcanoes to the right. They looked ruined, as if the white was quicklime corroding their solidity. A smear of vapour from the height of Ruapehu stretched east on the top of the sky; there was fire inside the snow.

Apirana drove ahead in his land rover. I followed about fifty metres behind in my car. We had agreed on my plan to go to Wellington. The first stop would be Taihape. He said there was no point in stopping at Waiouru; he had double-checked everything.

The air thickened as we drove down from the plateau through great clefts in the hills. The scrub browns gave way to greens, faded on the sheep-eaten hills, dusty by the road. The road slanted down. More vegetation appeared, some undefeated trees and patches of bush. Mostly it was chainsaw land. Every now and then, week-old dead possums lay on the road where trucks had hit them, bits of fur and leather innards, no flies or hawks to worry what was left. The land rover made swerves.

At each small town we halted and Apirana detonated a training grenade, a thunder flash. He showed me how they worked, compared with real hand grenades made out of metal, of which he also had a boxful in the land rover. The thunder flashes blasted violent waves of noise into empty streets and back at us from buildings and hillsides. Then silence. We would wait, then go on.

South of Taihape there were vistas of endless hills, like broken bones hidden under green baize. In places the road sliced through lumps of land leaving cuts exposed in the air. They were being corroded; gangrene had set in. Subsoil had fallen and dried. Yellow dust came up and powdered the windscreen. I wondered how long it would take for the bush to grow back and the hills to get firm roots again. A feeling of violation welded the past to the present, of extinct life forms feeding on extinction for revenge. The same negative presence was seething in the vacancy of human places as in the spaces where the forest had been and where the excavators had amputated whole sections of hills. I remembered driving from Cape Turnagain years before and feeling the threat of the emptiness getting at places inside myself. Even here where there were buildings, roads, and farms, they appeared furtive, as though not properly seen or not meant to be closely looked at for long; made in haste, unrepented. People spoke of the land being settled; in fact it had been unsettled. And now, absolutely.

The windscreen wipers cleared the view, made it hard. Suddenly I was startled by swarms of darting flecks in the air, swirling in the wake of the land rover. Thistledown. Like butterflies. Billions of seeds. For the rest of the way down to the plain there were these clouds of floating white specks. The weeds were on the move, not wasting time; it would be all theirs.

We detoured to Palmerston North. Apirana fired grenades, and we climbed to the top of a tall insurance building to scan the horizon with binoculars. There was a whitish heat haze, and no sound or sign of life. Descending, we ate what would have been lunch under the shade of a tree in the square. A white marble statue of a Maori chief stared from a dead rose garden at reflections in shop windows. Apirana walked around.

‘Why would they build a statue to a Maori?’ he said. He peered at the inscription. ‘Oh, yes. Might’ve guessed. For his loyalty in the Maori Wars. You know what that means?’

I said nothing. He shook his head.

‘Means he fought against the Maori.’

‘It was a long time ago,’ I said.

‘Not so long.’ He pointed. ‘It says, “I have done my duty. Do you likewise.” Well, well. How about that?’

I could tell he was trying to irritate me. We were both a bit on edge from the heat and the weariness of the drive through the vacant towns. Yet something about the words of the inscription seemed to goad him.

‘Who decides all this?’ he asked, tapping the letters with his knuckles. ‘They do. The ones who win. The ones who get the land in the end. He just backed a winner, that’s all.’

He came back and flung himself down in the shade. I wasn’t going to fight the Maori Wars with him. I could never understand this obsession with the importance of the ownership of land. Your people might have scratched around for a few generations on the top ten centimetres of a land two hundred million years old which had another four hundred million to go. In what impertinent sense of the word could you claim you ‘owned’ that piece of geology? By burial rights? Surely that would reverse the titles of claim and claimant? Nor had I ever sympathised with the idea that we Europeans had corrupted the noble savages. They were from the start devious, aggressive, and self-important, much like the rest of humanity. Western liberalism had now made them sanctimonious as well. I drank some wine. Even in the shade I felt choked with the heat.

‘Well, you’ve got it all now,’ I said.

‘All what?’

Читать дальше

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/books/28041/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island-zero-thumb.webp)