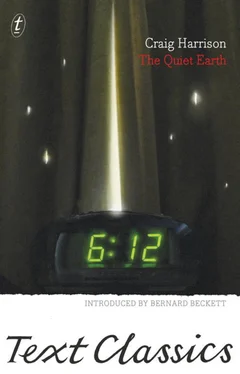

I hung onto the railing of the bridge and gazed into the water trying to see them. Yes! Again! The points of light flashed up all at once. How could I have racked my brain, driven all over the place, looked for everywhere, considered every aspect of the mystery, and not once wondered about the sea or the rivers?

It was a long time before I could walk onto the island. The sudden excitement drove the tiredness away. Then it came back, heavier. I couldn’t make any more sense of the Effect with the new information. Perhaps, if there was some significance, I would see it later. At least it was reassuring, to see living creatures and realise that lots of life still existed and went on existing as if nothing had ever happened. There was something defiant about the quickness of the fish, the way they caught the light in the clear water and flicked round all together in a crowd.

I broke into the small restaurant building on the island, went upstairs, and spread my sleeping bag on cushions on the floor after carrying in some of the equipment from the car. There was a handy kitchen in which I set up the gas-operated cooking unit and warmed up a few tins of food. After eating, before going to sleep, I cut the mould from a loaf of bread I discovered in the kitchen, and went back to the bridge. The loaf was dry and hard, but I pulled it apart and dropped the pieces into the river. The fish lunged at them. My hands were trembling.

I had a completely unconscious sleep, dreamless. It was early evening when I woke and the sun was saturating the air with a powerful golden radiation. I took the gun and crossed the river, drove back up to the town, and parked by the lakefront. The hills were slate-grey and purple, the sky an intense green towards the horizon. The sun went down with its light on the landscape like a nuclear forge throwing out a spectrum of all the elements: strontium reds, barium and copper greens, sodium yellow, silver chromates, blue cobalt, quicklime whites of calcium and magnesium, and brown ferrous oxides. And from the west the shadows spread out like heaps of carbon black tipped beneath the hills. My senses had extended and become more acute in the isolation of the last week, and visual images had taken on an energy of their own as well as the power to break into heightened perceptions from other senses. The force of the chemistry of these colours gave me the taste, scent, and touch of each separate element. The whites were hot and crumbling, the greens sharp, pungent, acid, the carbon soft and slippery like powdered pencil lead with its smell of sweat. Only my hearing had retreated from lack of work. The soundlessness of the beast that had slithered across the forest road had been as frightening as the sight. It might almost have been formed out of the solid silence which was squatting everywhere.

I turned to get back in the car to return to the island for the night, when I thought I heard something. From a long way off, seeming to come from as far away as the mountains at the southern end of the lake, there was a long booming noise, vibrating and changing pitch. It was impossible to tell what it was. The bellowing of a machine; an indecipherable compound of tones. Then it sounded again, or perhaps echoed, either from the hills or inside the drums and canals of my ears; I was straining hard to listen. It was mournful and weird. When it died away, the silence stood even thicker until a slight breeze began to ruffle the lake and hiss in the leaves of the taller trees by the shore. Perhaps it had been the movement of air, setting up a resonance, seeming further away than it was. Or even a volcanic, or a thermal noise; this was all an unstable area. Or maybe I had imagined it. I listened for several minutes, then, as the sun fell and the darkness began to grow, I got in the car and drove back to the sanctuary of the island. The river was like cold metal, the liquid of dead hills.

I had never considered what it would be like to become insane. The worst thing would be knowing it, being aware that it was happening. It would be gradual. The little rituals of sanity, the small items, would slip away. Lucid patches would contract and the light go thin until there would be huge areas of uncertainty. It seemed to me to be extremely sad and at the same time in the whole mystery of the world amazingly trivial that I should be insane.

In the night I woke and listened helplessly to the trees and the river. I wept for about five minutes. When I woke again it was a clear day.

I loaded the car and stood on the bridge looking at the water rolling beneath. There were broken clouds in the sky and the sun was being cut and dulled. Then the clouds would go and the heat press down on my neck. My reflection was on the surface of the water and my shadow lay on the riverbed below.

I put my sunglasses on and drove up the hill through Taupo, and left on the lakeside road south. The road swept up and then crawled down awkwardly between hills in sharp bends. Round one bend I nearly collided with an empty sheep truck and trailer jack-knifed across the road. I stopped, got out, and looked. The way was blocked. On the left, a wall of cliff and bush. On the right, a patch of soggy earth and ferns, then dense bush. I couldn’t move the truck. The batteries were dead and it had run dry of petrol. I consulted a map; either go back and round the lake on the other side, or go down State Highway 5 to Napier. It would take ages, and those roads would be narrow and might be blocked as well.

After testing the muddy patch and pulling aside some plants and tree branches I thought I could make it past the truck on the right. No sooner had I driven off the road than the back wheels sank and churned up the mud and in ten seconds the car was stuck. I got out and unloaded the boot and back seat to lighten the weight.

Then I wrenched some planks from the sheep truck and shoved them under the back wheels of the car. I found some rocks, rammed them into the ground, jacked up the right rear wheel and pushed rocks and a piece of plank under it. At the first attempt the wheels kicked out the wood and sank again. Covered in sweat and mud, I tried again. On the third attempt it worked and the car lifted out, found traction, and lurched forward over the firmer ground, scraping bushes on the right and bouncing back onto the road. Then I had to carry all the stuff round and reload.

The immediate problem had taken my mind off everything else and I felt better. I drove on along the winding road by the lake and past empty motels, caravans and campsites. Half an hour later I stopped on the bridge at Turangi and opened tins of corned beef and pineapple for a snack. The sun was coming and going. Turangi seemed less altered by depopulation than anywhere else I had seen. I couldn’t imagine anyone would live there by choice. The makers of the place must have been struck by the same puzzle, and had thrown the houses down and run away. The road, as I drove past, was like an escape route made for a massive burglary; but what had been stolen from this desolation was a mystery. The hills ahead on the right were dark against the sun, barren and sullen, as if vengeance had been involved and was not ended yet.

I speeded up for a couple of kilometres, then slowed down, cursing. There was another sheep truck and trailer across the road. This time there was no way round, just clumps of tussock and embankments of red earth. To the left, about thirty metres back, there appeared to be a way through the knots of gorse and small mounds of scrub and bracken-covered land. It might even have been a well-used track at some time. The ground looked quite firm, but in the distance there were blots of steam which suggested thermal pools. Maybe the track once led to a thermal area and there was no way back onto the main road. But it was worth trying.

Читать дальше

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/books/28041/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island-zero-thumb.webp)