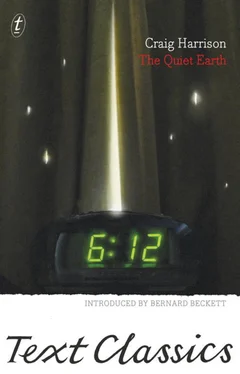

I went back into the motel, locked the door, and lay down to think. What did the curvature of space mean? That nothing really ended? That the stars which faded from one place reappeared somewhere else, and events curved back on themselves? If that happened, time would crumble, causes and effects would cease to be linear and sequential, and the laws of thermodynamics and entropy would contract from general principles to purely local phenomena.

Taking a strip of cardboard from one of the packets of food, I folded it into a loop. Inside surface, outer surface; top edge, bottom edge. Now, what was the trick? You disconnected the ends, twisted the strip once, and reconnected the ends. That was it. A Moebius loop. The inside and outside surfaces become continuous; and there is only one edge. Neither have any ending, they have become infinite. And the object only two dimensions. Yet it still exists in the three-dimensional world. Shadows are two-dimensional. You cannot pick them up. So this loop, this spiral, must be a trick of some kind. Or an anomaly in this universe. An ordinary shape with one simple kink in it becomes an impossibility with no beginning or end. Yet it exists.

What would I do tomorrow, and tomorrow?

Great questions; small answers. I would drive south to Wellington. Perhaps I might meet somebody or come across at least some form of clue or revelation. So far I was not able to piece together even the beginnings of a coherent idea. I did not consider returning to the research centre. I could not have forced myself to go back in there. The smell of death had gone too far down my throat. My escape, when I thought it over in the light of day, had been the result of a controlled scientific deduction, the application of logic to a problem. There were chemical equations to account for even the decomposition of the corpse which had been Perrin. I was aware that beneath the surface of all that logic were atavistic impulses and private terrors; they had always been there. As long as they did not link themselves to the phenomenal world created by the Effect, I would be safe. And yet every day seemed to set a greater space between my optimism of a solution and the likelihood that there would be one. It was like being on the platform of a deserted railway station wondering if you are too early or too late. You pace around, and wait, and look hard at ordinary objects; you stay, and wait, and nothing happens. There is no announcement. The waiting in one place becomes intolerable. Something terrible has occurred along the line. The explanation is somewhere else.

On Wednesday I loaded the car with my gear and drove to my flat in Takapuna. I approached it carefully, with a vague fear that it might contain a vengeance from forces cheated by my absence, a vacuum wanting my presence, impatient at waiting. Absurdly I checked the letterbox, as if expecting a summons. Shotgun cradled in my arm, I then unlocked the door, paused, and went in quickly. Of course the place was as I had left it. The normality was unnerving. I looked around, feeling intensely sorry for the person who had left here on Friday to go to Thames, gone so unsuspecting into such an enormity. This was the old world, like a museum now, full of objects that no longer worked or had any meaning.

I stayed only long enough to pick up some clothes and a few odds and ends, then drove away, back onto the motorway and across the bridge into downtown Auckland. The weather had changed. Grey clouds hung over the city. But it stayed hot and the clouds pressed the humidity closer. At first it was good to be rid of the bright of the sun beating down from empty sky, making day after day seem the same and searchlighting every millimetre of space. I was glad of the change. Then the clouds packed together overhead and stopped moving, and the density of the air buried even the sounds I made, and lay thick over the inner-city blocks.

I broke into a shop and took some clothes. There were stacks of cardboard boxes in the back of the shop. Heaping them in the middle of Queen Street I made a bonfire, ensuring plenty of smoke with the spare tyres of nearby abandoned cars before retreating to the vantage point at the top of the hotel building to scan all the streets for any signs of action or response. An hour went by. There was nothing. I toyed with the idea of setting fire to one of the insurance companies’ office blocks to make a real blaze. I could spread petrol over the ground floor; it would go up like a torch. Part of my mind was disturbed by the thoughts of destruction and the forward thrill I derived from this. The desire for violence, for an act of great power and senselessness that would be all mine and my gesture at the universe as well as at this city which had consumed my life, all this was immensely compelling. I went down the stairs to my car and drove away fast, dodging stalled trucks and fareless taxis to the motorway, south, the sweat flattening my shirt to my back. It had never been the buildings I had hated, only the people, and they were beyond retribution. Burning a tower would be pure spite, no catharsis, just kicking a hollow coffin.

Driving south I kept looking left. Had there been anything in Thames outside my room that night? When I thought about the sequence of events I realised there had been a close connection between my mind and what happened. What I had feared had seemed to happen. Then when I set my thoughts to resist the consequences, I had beaten them back. Was this a world in which the mind could promote events which then proceeded outside the mind, objectively, yet still capable of being influenced by thoughts? The boundaries between subjective and objective seemed to have blurred. The shift from one to the other was like looking through a window at an object and then finding yourself staring at your own reflection in the glass; a medium had changed its nature for no apparent reason. No; the medium stays the same, the mind makes the change.

Perhaps I had been in shock. But I couldn’t stop glancing left, down each road that led east. The nervous impulse persisted.

Hamilton was desolation. It was easy to see that nobody had survived, because nothing had been changed in any way. I dutifully checked the main streets, post office, police station and hospital. And there, outside the casualty entrance, an ambulance stood abandoned, its rear doors open. I got out of my car, the sudden tension liquefying my insides as usual, and walked past the vehicle into the hospital. A short way down the corridor there was a trolley topped with red blankets. Inside a nearby room there were beds. The first one I saw was as empty as the rest, but there were bloodstains patching the indented pillow dark brown, and a big spilled stain on the shiny lino floor by the bed. It had come from the inverted transfusion bottle hooked above the bed; the tube hung down loosely into space above the dry iridescent blot. The antiseptic scent in the room was mixed with a suffocating stench, a mucous of stale excretions. I turned and half-ran out, fixing my teeth and lips tight against the reflex of retching, holding my breath until the car was accelerating down the road and I could inhale fresh air.

Then, south of the city, I found the smashed cars which must have been the source of the casualties. Two impacted wrecks locked together were hemmed in at the side of the road by black and white traffic patrol cars, a fire engine and an ambulance, dead warning lights, then a line of stopped cars and trucks. The tarmac was scattered with crystals of windscreen glass, a woman’s shoe, a paperback book, a tartan blanket, a handbag, stretchers and tools. Black sump oil and dried rust-water stains ran away across the camber of the road like bleed marks spilled from the death of machinery, with broken flecks of rust and mud which had been bashed loose and flung all over.

Читать дальше

![Nick Cracknell - The Quiet Apocalypse [= Island Zero]](/books/28041/nick-cracknell-the-quiet-apocalypse-island-zero-thumb.webp)