Valeria said, ‘I’m sorry I doubted you. I’m sorry for what we’ve put you through.’

‘It’s all right,’ Clara assured her. The traveller put an arm around her shoulders.

‘Yalda’s really dead,’ Valeria said. ‘Years ago. Generations ago.’

‘Yes. But she had four wonderful children in the flesh, and in spirit you could call her the mother of us all.’

Eusebio leant against the window, covering his eyes.

Valeria composed herself. ‘When can we meet everyone? When are they coming to Zeugma?’

Clara said, ‘There’ll be other emissaries soon. Once I’ve reported back.’

‘But the Peerless —?’

‘The mountain itself won’t come down to the surface. People will be welcome to visit it, but most of the travellers won’t be settling on the home world.’

Valeria was astonished. ‘They’re going to stay inside?’

‘Some will,’ Clara replied. ‘It’s what they’re used to. Some might settle on the sun, opposite the engines, if it proves safe there.’

Valeria gazed down at the crevasse that divided Zeugma; from this height, in the starlight, it looked like a faint scratch.

‘Tell me about your family,’ she begged Clara. ‘Your father, your brother and sister, your co.’

Clara hesitated. ‘I don’t have that kind of family.’

‘They all died?’ Valeria was horrified.

‘No, no! Of course not.’

‘So… you’re a solo?’ With no father, so her mother must have fissioned spontaneously, like Valeria’s mother Tullia. ‘But you didn’t even have a brother and sister?’

Clara said, ‘Most of us have just one child. My mother shed me; I shed my daughter.’

Valeria understood. She felt a slight giddiness at the implications, then it gave way to a glorious sense of a new world spreading out beneath her gaze.

Eusebio turned from the window. ‘And who has the sons?’

Clara thought for a moment. ‘I said mother and daughter, but they’re not the right words. We tried very hard to live as men and women, but we couldn’t make that work, so we folded the two into one. My “mother” raised me as a father would, as I raised my own “daughter”.’

‘So you’ve wiped out all the men?’ Eusebio asked numbly.

‘No more than all the women,’ Clara insisted. ‘If I can promise myself to a child, how am I a woman? If my flesh can become that child, how am I a man?’

Eusebio looked sickened, but he fought to maintain decorum. ‘These are your choices,’ he said. ‘If we’re to accept your help, we should respect your culture.’

Valeria buzzed. ‘Could I be the father of my own child – and live to see her do the same?’

Clara said, ‘Yes.’

‘But what about my co?’

‘Between you, you’ll have to decide. He could be the father of your child, if you both wanted that.’

‘And I could still live? He could trigger me, and I could survive?’

‘Yes.’

Valeria looked down at the speck of light that had been her city. ‘Who did all these things? We have to know their stories.’

‘You will,’ Clara promised. ‘We had some good archivists, but I think the translations will need to be a collaborative project.’

‘How many generations was the voyage?’ Eusebio asked.

‘About a dozen.’

‘A dozen,’ he repeated. ‘An era.’

All of this had grown out of Eusebio’s endeavours – and in one year from the launch, not four. Valeria thought it must feel as if he’d stepped out of his house for a day and returned to find his children replaced by a whole vast swarm of descendants, all of them with strange ideas of their own.

Valeria said, ‘And how many people lived and died in the mountain, without seeing the end?’

Clara squeezed her shoulder. ‘A lot.’

Valeria pictured them, generation after generation, lined up across the years. Farmers and physicists, inventors and instrument builders, maintenance workers, millers and cleaners, biologists and astronomers. Hidden behind her outstretched thumb, for ever out of reach. ‘I wish I could talk to them,’ she said. ‘I wish I could thank them. I wish I could tell them that it wasn’t for nothing, that it ended well.’

Clara said, ‘If that’s what you want, then I believe you’ll find a way.’

Appendix 1: Units and measurements

Distance

1 scant (1/144 In strides )

1 span = 12 scants (1/12 In strides )

1 stride = 12 spans (1 In strides )

1 stretch = 12 strides (12 In strides )

1 saunter = 12 stretches (144 In strides )

1 stroll = 12 saunters (1,728 In strides )

1 slog = 12 strolls (20,736 In strides )

1 separation = 12 slogs (248,832 In strides )

1 severance = 12 separations (2,985,984 In strides )

Home world’s equator = 7.42 severances (22,156,000 In strides )

Distance from Peerless to the Object = 193 severances (576,294,912 In strides )

Home world’s orbital radius = 16,323 severances (48,740,217,000 In strides )

Time

1 flicker (1/12 In pauses )

1 pause = 12 flickers (1 In pauses )

1 lapse = 12 pauses (12 In pauses )

1 chime = 12 lapses (144 In pauses )

1 bell = 12 chimes (1,728 In pauses )

1 day = 12 bells (20,736 In pauses )

1 stint = 12 days (248,832 In pauses )

Peerless’s rotational period = 6.8 lapses (82 In pauses )

1 year = 43.1 stints (1 In years )

1 generation = 12 years (12 In years )

1 era = 12 generations (144 In years )

1 age = 12 eras (1,728 In years )

1 epoch = 12 ages (20,736 In years )

1 eon = 12 epochs (248,832 In years )

Angles

1 arc-flicker (1/248,832 In revolutions )

1 arc-pause = 12 arc-flickers (1/20,736 In revolutions )

1 arc-lapse = 12 arc-pauses (1/1,728 In revolutions )

1 arc-chime = 12 arc-lapses (1/144 In revolutions )

1 arc-bell = 12 arc-chimes (1/12 In revolutions )

1 revolution = 12 arc-bells (1 In revolutions )

Mass

1 scrag (1/144 In hefts )

1 scrood = 12 scrags (1/12 In hefts )

1 heft = 12 scroods (1 In hefts )

1 haul = 12 hefts (12 In hefts )

1 burden = 12 hauls (144 In hefts )

Prefixes for multiples

ampio- = 12 3= 1,728

lauto- = 12 6= 2,985,984

vasto- = 12 9= 5,159,780,352

generoso- = 12 12= 8,916,100,448,256

gravido- = 12 15= 15,407,021,574,586,368

Prefixes for fractions

scarso- = 1/12 3= 1/1,728

piccolo- = 1/12 6= 1/2,985,984

piccino- = 1/12 9= 1/5,159,780,352

minuto- = 1/12 12= 1/8,916,100,448,256

minuscolo- = 1/12 15= 1/15,407,021,574,586,368

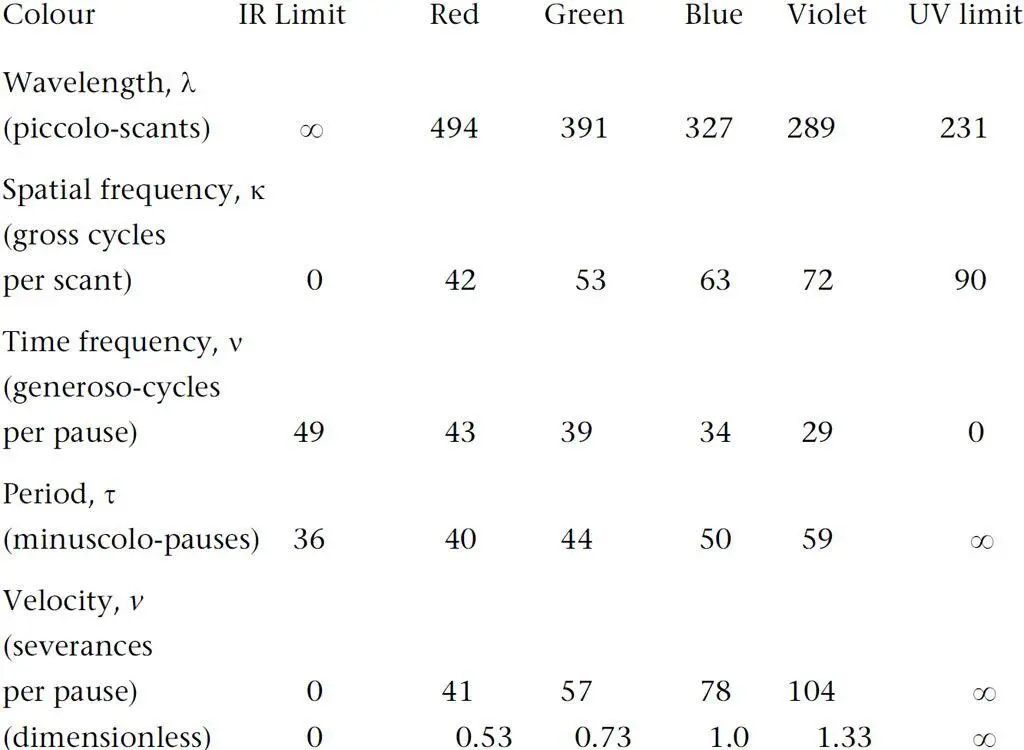

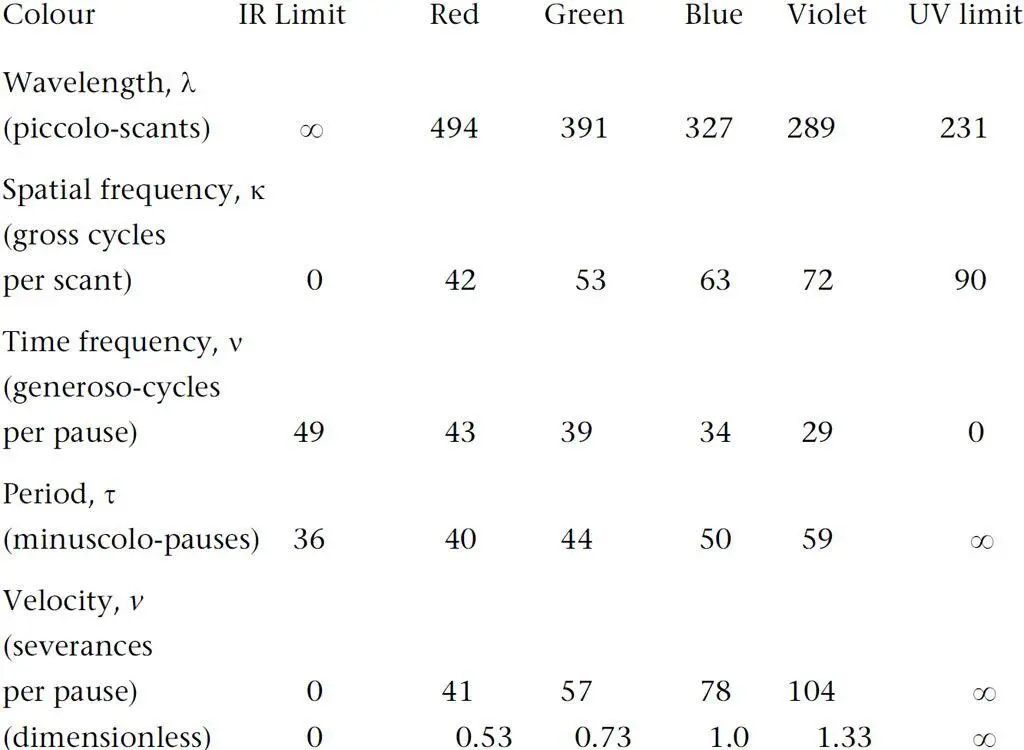

Appendix 2: Light and colours

The names of colours are translated so that the progression from ‘red’ to ‘violet’ implies shorter wavelengths. In the Orthogonal universe this progression is accompanied by a decrease in the light’s frequency in time. In our own universe the opposite holds: shorter wavelengths correspond to higher frequencies.

The smallest possible wavelength of light, λ min, is about 231 piccolo-scants; this is for light with an infinite velocity, at the ‘ultraviolet limit’. The highest possible time frequency of light, ν max, is about 49 generoso-cycles per pause; this is for stationary light, at the ‘infrared limit’.

Читать дальше