‘That’s true.’

‘But… ?’

Agata said, ‘Why would I wait six years for the chance to do this, and then sleep through half of it?’

Ramiro buzzed. ‘Fair enough.’

‘I used to hold vigils outside the voting halls,’ Agata recalled. ‘I’d watch the people come and go, watch the tallies rising.’

He said, ‘So when you take something seriously, you try to make the most of it?’

‘Yes. Is that so strange?’ Agata tried to judge his mood, and decided to take a chance. ‘Isn’t that what you and Tarquinia are doing? Making the most of your friendship?’ Ever since Azelio had confided his own suspicions about the pair’s activities to her, Agata had suffered bouts of curiosity, but she’d never had the courage to ask the participants themselves about the experience.

Ramiro didn’t seem angered by the question, or embarrassed. ‘In a way,’ he said. ‘If I was back on the mountain, I’d be worried that I was doing the opposite: taking the drive to raise children and wasting it on something trivial. Here, I can tell myself that I have no chance of becoming a father, so it’s not a waste at all.’

Agata said, ‘Everyone but the Starvers accepts that it makes sense to have children without fission – so why not refine the process even further and select precisely the effects we want from it?’

‘Why not?’ Ramiro agreed. ‘As an abstract proposition, it sounds as sensible as separating out the parts of a plant instead of blindly eating the whole thing. We don’t have to swallow the poisonous roots when it’s the stem that actually tastes good.’

‘But why as an abstract proposition?’ Agata pressed him.

Ramiro hesitated. ‘The trouble is, even when the body can’t put things back together, it never forgets how they used to be joined.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘It makes me want children more than ever,’ he said. ‘It takes that ache that might have faded with time, and reminds me, over and over again, that it’s never going to be fulfilled.’

While they were in free fall the Surveyor could be oriented any way they liked, and Tarquinia had chosen to set the window facing the rim of the hemisphere of home-cluster star trails. As Agata’s vigil stretched on, she left Ramiro in peace, ignored the clock on her console, and just stared out through the window, waiting for the first sign that something solid and invisible had moved between her and the ordinary stars.

Despite the lights of the cabin, after a few lapses her eyes began picking out a faint grey disc against the deeper blackness of the dark hemisphere. Esilio’s sun scattered ordinary starlight, so she could have checked its progress through the telescope without even switching to the time-reversed camera, but she was content to let the image remain elusive, coming and going as her concentration faltered, or as Ramiro shifted in his harness and drew her focus back to the reflected interior.

When a bite appeared in the rim of the bowl, all ambiguity vanished from the scene. Agata felt a tingling of excitement, and beneath it a churning sense of disruption. When the Surveyor had altered its velocity the star trails themselves had stretched and shrunk, but she’d seen the same predictable deformation when the Peerless turned around, and in the end it amounted to little more than holding up a distorting mirror to the sky. This was different: before her eyes, an orthogonal star was leaving its hemisphere and crossing the border, obscuring the ancestors’ stars behind it.

The occulted region grew larger, slowly revealing with clarity and precision the shape she’d squinted and guessed at. Agata savoured the delay still to come: she’d chosen reference points on the star trails well clear of the clutter of the rim, so it would be a bell or so before she could start making measurements.

Ramiro said, ‘I wonder what the settlers will call it: that day of the year when the sun starts its passage across the stars.’

Azelio and Tarquinia joined them, and the four of them ate breakfast together as they watched the black disc become whole. Then Agata turned to her console and summoned up the image through the telescope.

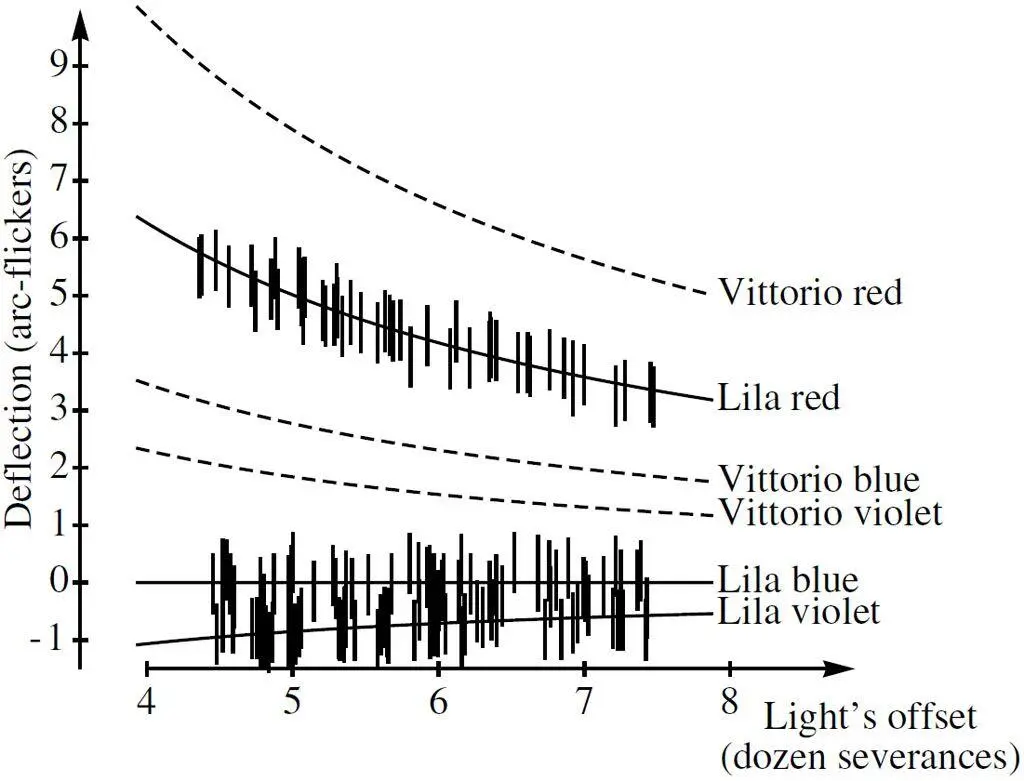

She guided the software as it tracked the celestial markers she’d chosen. Some were transitions in the perceptually defined hue of a single star trail: the point where orange turned to red, easy to find by eye though there was no discontinuity in the light’s actual wavelength. Others were points where two trails crossed, and were not so much fixed beacons as sites where she expected some complicated but illuminating slippage. The colours of the two trails were never the same where they met, so two beams that were initially travelling side-by-side would be bent by different amounts depending on their speed, leaving a slightly different pair of hues to meet up in their place.

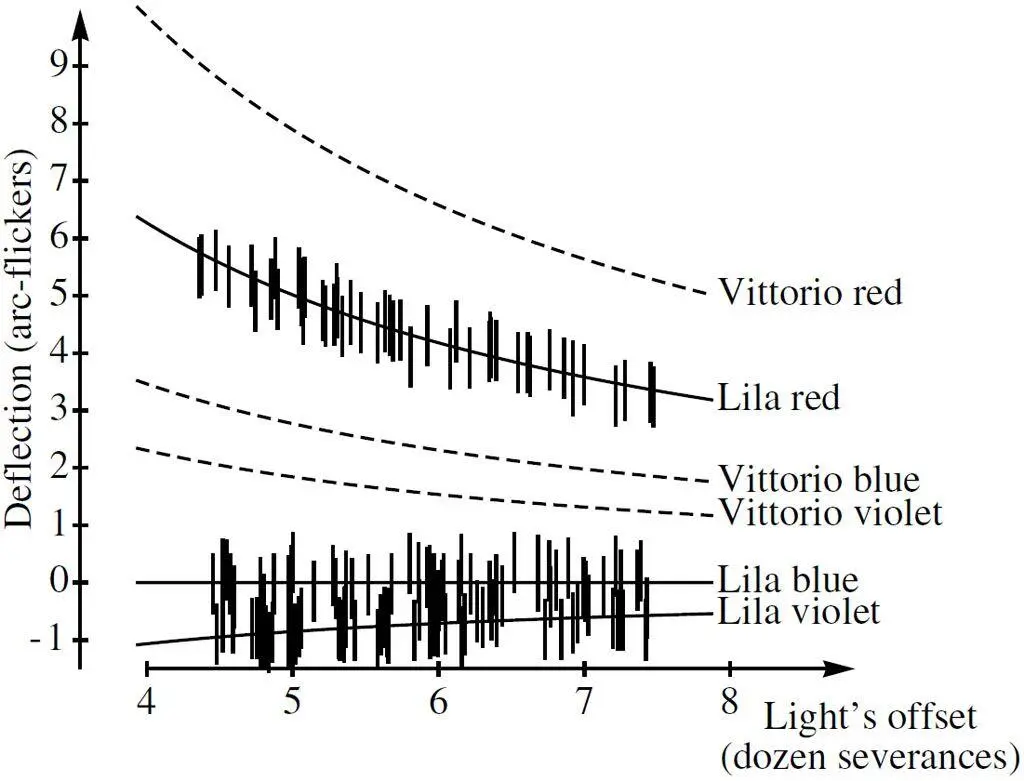

Agata didn’t expect any telltale distortion to leap out at her from the screen; the changes would be measured in arc-flickers. All she could do was check that the software had latched on to the correct features, and watch closely to ensure that nothing went awry as the black disc encroached on the field of view.

She did not take her eyes from the telescope’s feed until the last of the markers had vanished behind the sun. Then she summoned the analysis: a plot of measurements compared to predictions.

‘Azelio?’ she called.

‘Yes?’

‘Prepare to skip lunch; I’ll be eating for both of us.’

Azelio dragged himself over to take a look at the results, soon followed by Ramiro and Tarquinia. The measurements with their spread of errors wove a course that hewed closely to Lila’s predictions – and ruled out Vittorio’s theory entirely.

‘Space is curved!’ Tarquinia exclaimed delightedly. She’d taken no prior position on Lila’s theory, but the sheer strangeness of the notion seemed to please her now that it could finally be justified.

‘Very slightly,’ Azelio conceded. ‘It’s barely measurable.’

‘This might seem like a tiny, obscure effect now,’ Tarquinia replied, ‘but I guarantee that in a couple of generations, every astronomer will be making use of it somehow.’

Ramiro squeezed Agata’s shoulder. ‘Congratulations.’

She said, ‘It was Lila’s prediction, not mine.’

‘And yet I don’t see Lila here making the measurements.’

‘When I told her I was going to be doing this,’ Agata recalled, ‘she said: “If the results aren’t what my equations dictate, all we can do is pity the poor cosmos – because true or not, the theory will be the more beautiful of the two by far.“ ’

‘So you’ve proved that the cosmos is beautiful,’ Azelio concluded. ‘But you still can’t tell us its shape.’

‘The beauty is that it’s comprehensible,’ Agata declared. ‘Even if its shape is unknown.’

‘Unknown to you,’ Ramiro said provocatively.

‘Yes.’ Agata frowned. ‘But why the distinction? Have you been working with Lila’s equations yourself, on all those long watches?’

‘Ha! I wish I were that smart.’

‘Then who… ?’

‘If the messaging system’s been operating on the Peerless since a year or so after we left,’ Ramiro reasoned, ‘then Lila and her students will have had a year by now to think over all the results we bring back. So who knows how far they might have taken things?’

‘That doesn’t bother me,’ Agata said firmly. ‘I’ve stolen an advantage over everyone on the Peerless , squeezing three years into each year that passed for them. If they end up deriving some beautiful corollaries from my results by the time I return, that will give me the best of both worlds: I’ll get to see what other people make of my work – and I won’t even have to wait around while they do it.’

Читать дальше