‘That’s just greedy,’ Medoro said. He was keeping his face calm and happy for Arianna, with a voice to match, but Agata could tell that none of this warmth was intended for her.

‘You make your choices, I’ll make mine,’ she said.

‘And what if it’s impossible?’ he taunted her. ‘They can pump as much light into your body as they like, but if the man you want them to wake isn’t in there, he isn’t in there.’

Agata said, ‘Wait and see. Maybe you’ll get a message from Arianna soon enough, letting us all in on the answer.’

‘Spheres are simply connected,’ Lila said. ‘Don’t you think that’s the key?’

‘Perhaps.’ Agata let her rear gaze drift, taking in the crammed bookshelves behind her. Generations of knowledge were packed in there, revelations dating all the way back to Vittorio. She could smell the dye and the old paper – a scent that had always delighted her, promising the thrill of new ideas – but by now she’d absorbed the contents of those shelves so thoroughly that nothing from the past still had the power to astonish her.

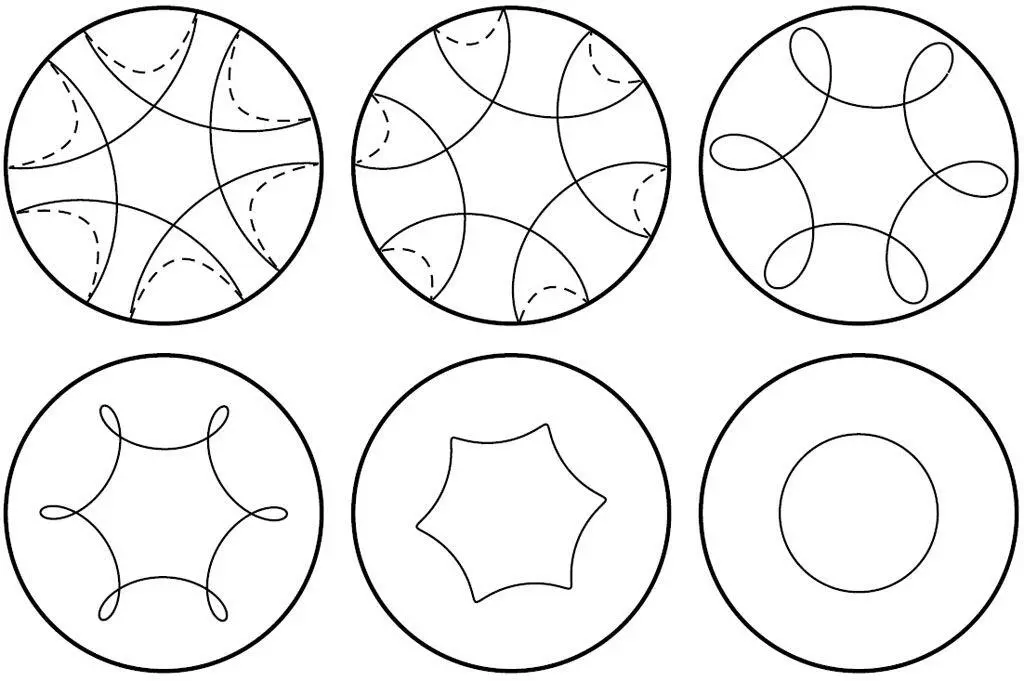

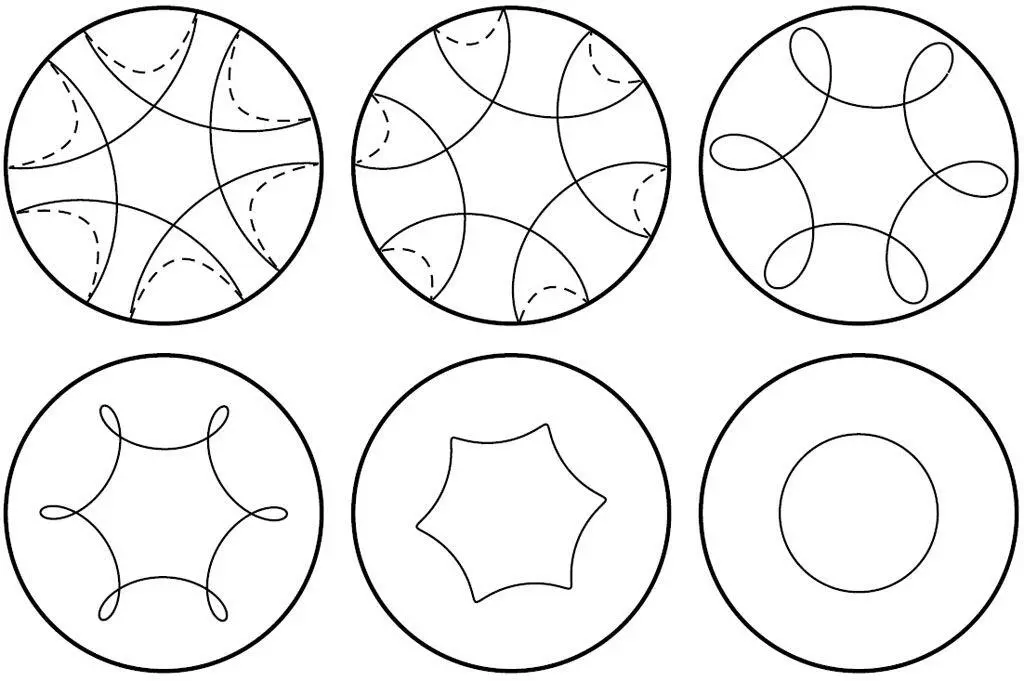

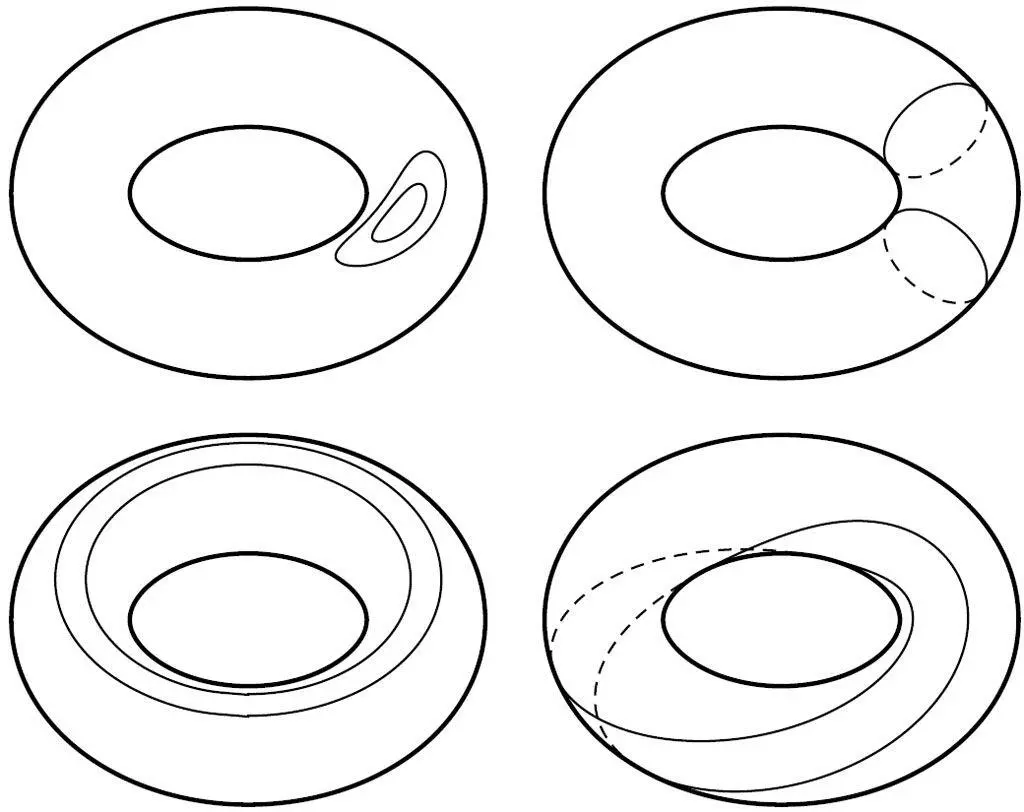

‘Any loop on a two-dimensional sphere can be deformed into any other,’ Lila mused, doodling an example on her chest of an elaborate loop being transformed into a simpler one.

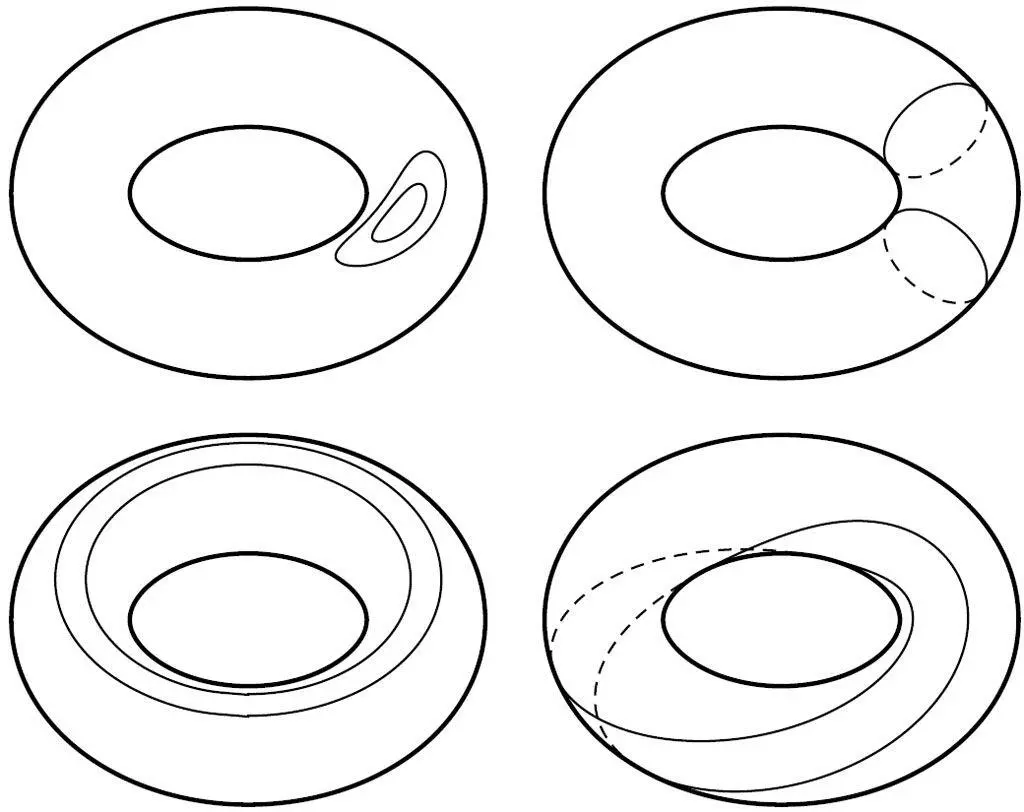

‘But on a torus, you can’t change the number of times the loop winds around the space in each dimension, so there are an infinite number of different classes.’ She sketched examples from four of them – pairs of loops that could be transformed into each other, because they shared that distinguishing set of numbers. No amount of stretching or shrinking could take a loop from one class to another.

Lila hesitated, as if expecting Agata to pick up the thread, but after half a lapse she lost patience and prompted her: ‘So what can we say about a four-sphere?’

Agata struggled to concentrate. ‘It’s the same as the two-dimensional case: there’s only one class of loop.’ She could wind an imaginary thread a dozen times around the four-sphere, weave and tangle it any way she liked, but if she tried removing all those complications and shrinking the loop down to a plain circle, nothing she’d done and nothing about the space itself would obstruct her.

‘And is that true of the cosmos we live in?’ Lila pressed her.

‘How would we know?’

Lila said, ‘If you can find a good reason why it has to be true, that would be the key to the entropy gradient.’

Agata couldn’t argue with the logic of this claim, but she didn’t have high hopes for satisfying its premise. ‘I don’t see how it could ever be forced on us. The solutions to Nereo’s equation are just as well behaved on a torus as they are on a sphere.’

‘Then perhaps we need to look farther afield. You must have some new ideas on this that you want to pursue.’

Lila gazed at her expectantly. Agata felt her skin tingling with shame, but she had no inspired suggestions with which to fill the silence. ‘I’ve been a bit distracted by my new duties,’ she said.

‘I see.’ Lila’s tone was neutral, but the lack of sympathy made her words sound like an accusation.

‘I know that’s no excuse,’ Agata said. ‘Everyone has to help keep things running until the strike’s over. But when my mind’s blocked, what can I do?’

Lila adjusted herself in her harness. ‘That depends on the nature of the obstruction.’

‘It can’t always have been easy for you,’ Agata protested. ‘You must have got stuck yourself, sometimes.’

‘Of course,’ Lila agreed. ‘But I was never forced to contemplate the imminent arrival of messages from a culture that had solved all my problems so long ago that any bright three-year-old would know the answers. I doubt that would have done much for my motivation.’

Agata said, ‘I’m not expecting any help from the future. That would make no sense.’

Lila inclined her head, accepting the last claim. ‘You’ve made a good argument for that. But I’m not sure that you’ve convinced yourself as thoroughly as you’ve persuaded me.’

Agata was unsettled. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Ever since the messaging system was mooted, you’ve been like this.’ Lila waited for her to object, but Agata was silent. ‘Maybe it’s just excitement at the prospect of the thing itself, or the distraction of all the politics. But be honest: can you really block it out of your mind that you might soon be reading the words of people who’ve had six more generations of prior research to call on than you’ve had?’

Agata said, ‘What does it matter, if they can’t communicate any of it?’ Lila claimed to have accepted her argument: complex ideas were far more likely to remain unmentioned in the messages than to arise without clear antecedents.

‘What matters is that it seems to have paralysed you.’

Agata struggled to recall some small achievement she could hold up against this claim, but since she and Lila had proved their conjecture on the curvature of four-spheres she’d really done nothing but mundane calculations. ‘Everyone gets stuck,’ she said. ‘I’ll snap out of it soon enough.’

Lila said, ‘I hope so. Because once you learn whether you do or you don’t, it’ll be settled for good, won’t it?’

Agata had set her console to wake her early. She ate quickly, then made her way to the axis and propelled herself down a long weightless shaft, touching the guide ropes lightly to keep herself centred.

She followed the shaft all the way to the bottom, emerging on a level that housed what remained of the feeds for the old sunstone engines. She dragged herself through chambers full of obsolete clockwork, the mirrorstone gears and springs tarnished and clogged with grit, but still offering up a dull sheen in the moss-light. For a year and a half after the launch, mechanical gyroscopes had tracked the mountain’s orientation, and the feeds’ machinery had kept the engines balanced by adjusting the flow of liberator trickling down into the sunstone fuel. Agata doubted that anyone at the time had imagined that a piece of photonics the size of her thumb would take the place of all these rooms.

As she moved further away from the axis, the chambers’ erstwhile floors became walls. Descending the rope ladder that crossed the third room, she passed precariously dangling assemblies of gears and shafts spilling out of their cabinets, the pieces still loosely bound together against the long assault of centrifugal gravity. The eruptions looked almost organic, as if the neglected cogs were sprouting from exuberantly blossoming vines. There must have been people inspecting and maintaining all of this quaint machinery, up until the day when Carla finally proved that none of it would ever be needed again. Now it would only take a couple more rivets snapping for these strange sculptures to come crashing down.

Agata left the decrepit clockwork behind, and dragged herself down a narrow passage to the shabby office of her supervisor, Celia. The office itself looked as old as the Peerless , but Celia’s networked console was a slab of bright modernity among the ruins – its roster of volunteers encrypted, for what that was worth when every strike-breaker could be seen coming and going. Celia handed her an access key and tool belt, and Agata signed for the equipment with a photonic patch, not dye.

‘This must seem pretty menial to you,’ Celia teased her. ‘Your predecessor wasn’t much into cosmology.’

Читать дальше