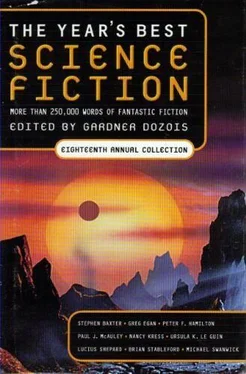

Gardner Dozois - The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Gardner Dozois - The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“A spare brain?”

“An auxiliary brain.”

“What would you do with that?”

“What wouldn’t you do with that, Mr. Giddens.” He wiped his hand across his mouth. “This bit is pure speculation, but…”

“But.”

“But in some way, she’s in control of it all. I think-this is just a theory-that through this auxiliary brain she’s able to interact with the nanoprocessors. She might be able to make them do what she wants.

Program them.”

“Thank you for telling me that,” I said bitterly. “That makes it all so much easier.”

I took the policemen back to my house. I told them to make themselves tea. I took Ten’s neatly arranged books and CDs off my shelves and her neatly folded clothes out of my drawers and her toilet things out of my bathroom and put them back in the two bags in which she had brought them. I gave the bags to the policemen, they took them away in their car. I never got to say goodbye. I never learned what flight she was on, where she flew from, when she left this country. A face behind glass. That was my last memory.

The thing I feared-insane, out of nowhere-had taken her away.

After Ten went, I was sick for a long time. There was no sunshine, no rain, no wind. No days or time, just a constant, high-pitched, quiet whine in my head. People at work played out a slightly amplified normality for my benefit. Alone, they would ask, very gently, How do you feel? “How do I feel?” I told them. “Like I’ve been shot with a single, high velocity round, and I’m dead, and I don’t know it.”

I asked for someone else to take over the I-Nation account. Wynton called me but I could not speak with him. He sent around a bottle of that good Jamaican import liqueur, and a note, “Come and see us, any time.” Willy arranged me a career break and a therapist.

His name was Greg, he was a client-centered therapist, which meant I could talk for as long as I liked about whatever I liked and he had to listen. I talked very little, those first few sessions. Partly I felt stupid, partly I didn’t want to talk, even to a stranger. But it worked, little by little, without my knowing. I think I only began to be aware of that the day I realized that Ten was gone, but not dead. Her last photo of Africa was still on the fridge and I looked at it and saw something new: down there, in there, somewhere, was Ten. The realization was vast and subtle at the same time. I think of it like a man who finds himself in darkness. He imagines he’s in a room, no doors, no windows, and that he’ll never find the way out. But then he hears noises, feels a touch on his face, smells a subtle smell, and he realizes that he is not in a room at all-he is outside: the touch on his face is the wind, the noises are night birds, the smell is from night-blooming flowers, and above him, somewhere, are stars.

Greg said nothing when I told him this-they never do, these client-centered boys, but after that session I went to the net and started the hunt for Tendeleo Bi. The Freedom of Information Act got me into the Immigration Service’s databases. Ten had been flown out on a secure military transport to Mombasa.

UNHCR in Mombasa had assigned her to Likoni Twelve, a new camp to the south of the city. She was transferred out on November Twelfth. It took two days searching to pick up a Tendeleo Bi logged into a place called Samburu North three months later. Medical records said she was suffering from exhaustion and dehydration, but responding to sugar and salt treatment. She was alive.

On the first Monday of winter, I went back to work. I had lost a whole season. On the first Friday, Willy gave me print-out from an on-line recruitment agency.

“I think you need a change of scene,” he said. “These people are looking for a stock accountant.”

These people were Medecins Sans Frontiers. Where they needed a stock accountant was their East African theater.

Eight months after the night the two policemen took away Ten’s things, I stepped off the plane in Mombasa. I think hell must be like Mombasa in its final days as capital of the Republic of Kenya, infrastructure unravelling, economy dis-integrating, the harbor a solid mass of boat people and a million more in the camps in Likoni and Shimba Hills, Islam and Christianity fighting a new Crusade for control of this chaos and the Chaga advancing from the west and now the south, after the new impact at Tanga.

And in the middle of it all, Sean Giddens, accounting for stock. It was good, hard, solid work in MSF Sector Headquarters, buying drugs where, when, and how we could; haggling down truck drivers and Sibirsk jet-jockeys; negotiating service contracts as spare parts for the Landcruisers gradually ran out, every day juggling budgets always too small against needs too big. I loved it more than any work I’ve ever done. I was so busy I sometimes forgot why I was there. Then I would go in the safe bus back to the compound and see the smoke going up from the other side of the harbor, hear the gunfire echo off the old Arab houses, and the memory of her behind that green wired glass would gut me.

My boss was a big bastard Frenchman, Jean-Paul Gastineau. He had survived wars and disasters on every continent except Antarctica. He liked Cuban cigars and wine from the valley where he was born and opera, and made sure he had them, never mind distance or expense. He took absolutely no shit. I liked him immensely. I was a fucking thin-blooded number-pushing black rosbif, but he enjoyed my creative accounting. He was wasted in Mombasa. He was a true front-line medic. He was itching for action.

One lunchtime, as he was opening his red wine, I asked him how easy it would to find someone in the camps. He looked at me shrewdly, then asked, “Who is she?”

He poured two glasses, his invitation to me. I told him my history and her history over the bottle. It was very good.

“So, how do I find her?”

“You’ll never get anything through channels,” Jean-Paul said. “Easiest thing to do is go there yourself.

You have leave due.”

“No I don’t.”

“Yes you do. About three weeks of it. Ah. Yes.” He poked about in his desk drawers. He threw me a black plastic object like a large cell-phone.

“What is it?”

“US ID chips have a GPS transponder. They like to know where their people are. Take it. If she is chipped, this will find her.”

“Thanks.”

He shrugged.

“I come from a nation of romantics. Also, you’re the only one in this fucking place appreciates a good Beaune.”

I flew up north on a Sibirsk charter. Through the window I could see the edge of the Chaga. It was too huge to be a feature of the landscape, or even a geographical entity. It was like a dark sea. It looked like what it was…another world, that had pushed up against our own. Like it, some ideas are too huge to fit into our everyday worlds. They push up through it, they take it over, and they change it beyond recognition. If what the doctor at Manchester Royal Infirmary had said about the things in Ten’s blood were true, then this was not just a new world. This was a new humanity. This was every rule about how we make our livings, how we deal with each other, how we lead our lives, all overturned.

The camps, also, are too big to take in. There is too much there for the world we’ve made for ourselves.

They change everything you believe. Mombasa was no preparation. It was like the end of the world up there on the front line.

“So, you’re looking for someone,” Heino Rautavana said. He had worked with Jean-Paul through the fall of Nairobi; I could trust him, Jay-Pee said, but I think he thought I was a fool, or, all at best, a romantic.

“No shortage of people here.”

Jean-Paul had warned the records wouldn’t be accurate. But you hope. I went to Samburu North, where my search in England had last recorded Ten. No trace of her. The UNHCR warden, a grim little American woman, took me up and down the rows of tents. I looked at the faces and my tracker sat silent on my hip. I saw those faces that night in the ceiling, and for many nights after.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

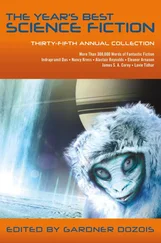

Похожие книги на «The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Years Best Science Fiction, Vol. 18» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.