What she never did understand was when erstwhile Loyalists and Rebels began to meet in pubs. That they joined hands in public to encourage rebuilding efforts was expected. She herself, as Governor-pro-tem, had pleaded with them to do so in live broadcasts and personal speeches down the length of the Vale. Also, they knew that, in case of disturbance, the 33rd was instructed to “step in the middle and shoot both ways.” But that they gathered privately in pubs in the evenings to retell stories of the Burning of Da Derga’s Hostel or the Massacre of the Gardies and sing mournful songs of the Storming of Council House or the March of the Meathmen, impartially celebrating the feats of each side…this eluded her entirely. When her lieutenant-colonel told her of one song—“Little Hugh Has Gone Away”—in which one verse revealed her own last-minute forbearance and ascribed it to a secret admiration for the Ghost, she thought for a moment of suppressing it. But Handsome Jack advised otherwise. “We sing and dance at wakes out here,” he explained. And later she heard him humming the selfsame tune at his desk in the Trade Office.

All of which convinced her that the Eireannaughta were mad.

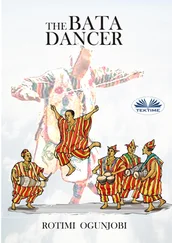

Meanwhile, she had this clever little prehuman statue. A stone that somehow danced. She would stare at it for hours, trying to catch it in the act of changing, only to realize after some time had passed that it had changed. She knew she would have to surrender it to the Central Office on Old ’Saken, because there would be no profit from it until it went on auction, but in the meantime it was hers. She had January’s sworn affidavit of provenance, chopped by his crew as well, and embellished by a clever little story, undoubtedly fabricated to frighten off would-be claim-jumpers. To this, she added her own affidavit to attest to the chain-of-custody.

And all this in exchange for a chit for maintenance-and-repair at the ICC Depot on Gladiola plus the promise of a share in the eventual auction proceeds. It was a fair percentage for a finder’s fee; but January had not even asked whether Jumdar had the authority to offer it. Privately, she hoped the Board would honor her promise. The ICC could be generous when it didn’t cost much; and January would get a ship almost like new; so he had no complaints coming.

The sandstone fit so comfortably in her hand that she took to carrying it with her. Like a scepter, some pardoned Loyalists in New Council House grumbled, and their Rebel coworkers agreed, for they hadn’t fought to make a Queen.

Yet, the proclamations she issued seemed reasonable, even inspired, and the people who heard her threw themselves into the Reconstruction with a fervor equal to their previous fury. There was even talk in some quarters, admittedly brief, that having a Queen was not so bad an idea. Jumdar seemed to get things done, and although some of the Guides in their remote Reek-side cabins grumbled about the “kiss-ass” of their fellow citizens regarding ICC dictates, everyone agreed that the dictates made good sense in the wake of what had gone before.

The wake of what came later was a different matter.

“A goltraí, then,” the harper says. “A Lament for Hugh O’Carroll.” And her harp sings so mournfully that half the patrons in the room grow inexplicably teary-eyed.

The scarred man listens for a while, but without visible effect. “They are mad, you know,” he says. “The Eireannaughta are. But what can you expect from a folk who live on a raft upon a sea of seething magma? The Big Blow can come at any time, so it’s not surprising that they themselves erupt now and then.”

“Did Jumdar intend to keep the Dancer, or did she really mean to send it to Old ’Saken?”

“Not at first, I think; and in the end, it wasn’t her decision to make. What happened to Jumdar is of little interest, except to Jumdar. No, if you must have a lament, the truly tragic figure in the story is Handsome Jack Garrity.”

The harper is surprised and her fingers hesitate and still. “Is he? Why?”

“Because he was a man who won everything and gained nothing, and what worse fate is there than that? He found himself a deputy commissioner in a minor office. Small beer for the Hero of New Down Town. That’s why his struggle with the Ghost came to consume him. It was the one time in his life when he had mattered.”

The harper strums a mockingly conventional military march. “I’d not call him a hero.”

“No? What is a hero, then? Surely, a man larger than life, who acts with courage, who controls his contending emotions—his anger, fear, and despair—to achieve his goal. Handsome Jack did not succumb to despair until after he had won. Can only those be heroes who show courage in causes you favor? The Ghost of Ardow, maybe?” The scarred man gestures broadly with his arm, as if the Ghost has entered the Bar and the scarred man is introducing him.

“No.” And her earlier Lament turns twisted and jangled, and she sets the harp down at last and balls her hands on the table. “But I had thought he was a better man. Not an assassin, not a murderer.” She seems much affected. There are, it appears, emotions whose music is silence.

The scarred man laughs hideously. “But give him this much: at least he excelled. We suppose there is a difference between killing a particular man quickly and efficiently, and killing many men wholesale on a battlefield. Maybe you can explain the difference to us.”

“The heroic man,” she says quietly, “conquers himself.”

At this, the scarred man falls silent for a while. Then he takes his uisce bowl and spins it toward the far side of the table, where the harper snatches it before it falls off. “That’s a struggle,” he suggests darkly, “in which some of us find ourselves outnumbered.” He looks at the bowl and then at the harper.

The message is clear. She signals to the Bartender, and shortly, the “water-of-life” has been replenished. The harper receives unasked a bowl of her own, and she raises it to her lips. It is an awful, numbing liquor with the one obvious purpose of numbing something awful.

“Do you know what’s funny?” the scarred man asks her. But he doesn’t wait for an answer. “Hugh O’Carroll was a schoolteacher by vocation. That was why he was in the Southern Vale when it all broke out. All he ever wanted to do was teach children.”

“Where did he go?” the harper asks. “Where did his men address the crate?”

The scarred man grins like a skull. “Where does any such residuum wash up?”

“Ah.” The harper turns and looks out at the Barroom and studies the men in it. “Not a very glorious end for a legend.”

“Who says that was the end? It wasn’t the end of the man, nor even of the legend, though legends are always harder to end. We spoke, he and I, at that table there by the window”—a bony finger points—“and we got the whole story out of him.”

The harper reaches for her instrument. “So, then it’s to Jehovah next.”

“No. There is one more beginning.”

Suantraí: Breaking on the Peripheral Shore

It began near the Rift, the scarred man says…

…a region where despair has become a feature of the sky. A place where some ancient god had drawn a knife across the galaxy’s throat and left a black gaping flow of blood. In this void there are no suns—or no living suns, an emptiness made all the less bearable by the surrounding shores of light.

On the farther shore of this hole in the sky gleam distant suns with magic names—Dao Chetty, Tsol, the Century Suns—stars whose worlds are storied in antiquity: strange worlds, ancient worlds, decadent worlds, worlds of peculiar and exotic customs. From the hither shore, they appear as they once had been: antique light hundreds of years on the journey, the lamps of the Old Commonwealth before it crumbled. A telescope subtle enough might still glimpse those halcyon days in the tardy images just now breaking on the Peripheral shore.

Читать дальше