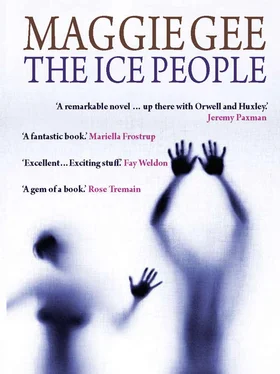

Maggie Gee - The Ice People

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Maggie Gee - The Ice People» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Telegram Books, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Ice People

- Автор:

- Издательство:Telegram Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ice People: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Ice People»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

imagines an ice age enveloping the Northern Hemisphere. It is Africa’s relative warmth that offers a last hope to northerly survivors. As relationships between men and women break down, the novel charts one man’s struggle to save his alienated son and bring him to the south and to salvation.

Maggie Gee

The White Family

The Flood

The Ice People — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Ice People», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We were a team, too. We had done it together. Without Briony, I couldn’t have started the engine, and Luke had encouraged me, helped me steer. Even Dora had given us the light from her eyes.

No, not a team, a family. The members of a team are all alike, men with men, women with women. Our family was not like that. Difference was the point. We were complementary. Everyone had something different to give.

Human beings weren’t meant to be segged. We were never intended to be solitary. The links stretched back through the generations, gifts of memory, gifts of genes. My father’s gift was concealed in my pack, sheathed in xylon, our most precious possession, the birth certificates, the documents. Samuel’s gift, of which he never knew the value, to the grandson he could not hold as a baby, so small, so skinny, so very white. (Dad said to me, after an awkward pause, ‘Congratulations, Saul. We-ell … You never would believe that this was my grandson.’)

Now Samuel’s blood was going to save Luke’s life. Opening the gates of Africa. Giving us the key to the last warm places, the retreating deserts where fruit would grow, the great grassy plains that had once been sand, the blueing hills, the returning streams, the sapling woods of the new green Sahara.

14

I suppose you never know who you are until your life is over. What you are is the sum of what you do — leavened with wishes, dreams, regrets — but I never knew half of what I could do until I was prised from my shell of habit.

I found I could sail across the Channel, which after all is a limb of the Atlantic. I could barter, in French, a boat for a car, and not do too badly on the deal. I could come across as tough, and taciturn. I could make people afraid of me. I could do without sleep, and books, and good food, and buzzers and soothers and all the rest …

I could live at a slower speed than before, rougher and slower, because I had to. Cars in Euro were a different life-form to the speedy hydrocars we drove at home. Since half of Paris was burned to the ground in 2056, the year before our journey, by the explosion at the hydrogen plant at Boulogne-Bilancourt, there had been no fuel for hydrocars, so the old bangers had come into their own, poor people’s cars, essentially, a few still running on blackmarket petrol, more of them adapted to run on alcohol that enterprising peasants brewed from plants. Hemp plants mostly, after smoking the leaves. You soon got used to the sweet, choking smell. But the car we’d got hold of, a red battered thing which had green and yellow fins painted on the back, did forty kilometres an hour flat out — pretty average for a French Alco — and you couldn’t go flat out through unfamiliar country where most of the signposts had been burnt for firewood. Sometimes it felt as if we were crawling, covering eighty kilometres a day. I began to understand what I’d never grasped when we flew all over Euro in less than halfanhour, when we slid like silk over the surface of things — that the world was large, and wild, and hard.

I could smash down the shutters of deserted houses, break in through other people’s windows. I felt nothing, looking at the scattered glass from a family photo in a brass frame. My family mattered more than them. I learned staying alive mattered more than anything, staying alive to protect my son.

Once I broke in and found a middle-aged woman whimpering with terror in the kitchen. Her face was a slab of tearstreaked white. She stared, transfixed, as if I might kill her. I took what we needed as if she weren’t there, and left her twitching, shivering, pleading. Perhaps she was mad, and had been abandoned months ago by indifferent children. Perhaps the father had stolen her children … I forced myself to act, not think, but I’ve never forgotten the colour of her eyes, blackishgreen like an oiled mallard, and her greasy dark hair, licked to her scalp.

I could forage for food and always find something, always enough to keep us alive, for the fleeing French never took it all with them, there were always tins of chestnut purée or vacuum packs of langue de chat biscuits or apple compôte or great wheels of cheese. We sometimes ate almost too well, in the north, on greasy pâtés or confit of duck, food that made poor Luke want to throw up, for he was used to spartan vegetarian fare, but we nagged him to eat it, and sometimes he did.

I could wring the necks of chickens. That was a shock, how easy it was, once you caught the damn things, with their hysterical squawking and long scrabbling feet and outraged eyes, once you’d felt the pain of their steely peck on your naked hand, it was easy to kill them, to squeeze and twist their long leathery craws with their prickly unpleasant ruffs of feathers. I could pluck them, too, once Briony taught me. Her mother had owned a battery farm, and she wouldn’t eat meat for our first few weeks, but by the end of March she was eating everything.

I could make a fire, lighting up every time, persevering even if the wood was wet, and cook whatever we found, very badly, either boiling it or burning it, in a cooking pot stolen in Normandie.

I could fish, with a line that Luke and I made, and we enjoyed it, father and son. But we never caught very much with the line, though we once removed halfadozen gasping and wriggling ornamental carp from a pond by hand, overcoloured orange and vermilion things. ‘Like taking candy from a baby,’ said Briony. She skinned them and fried them over the fire, and we ate them, and it was like eating salted leather, and Briony threw them up in the bushes. ‘That’s a waste,’ said Luke, transparently gleeful, which was what we’d told him, a hundred times.

I could drive the car for eight hours at a stretch before I yielded the wheel to Briony, then sleep in the back while she did her stint. I could steer by the sun, without uptodate maps — too much of a risk to try to buy them on the road, a way of advertising our foreignness. Besides, how could we know which of the furtive little shops still open in the rows of closed steel shutters sold anything but looted possessions? No maps would have shown the reality, in any case, the towns abandoned in the rush to the sun, the places where meganauts had crashed across the road and been left to rust once the looting stopped, or where there had been great fires in the riots and black melted plastic, several metres deep, made the route we had planned an inky nightmare, fantastic skewed nests of dark loop and curve. We could never relax, because the road might end, or the little black shape buzzing innocently towards us might prove to be a carload of bandits — but I could cope, I could handle it.

I could travel with a loaded gun in my lap, and be ready to use it when I had to. The worst time was one day when Briony was driving, I’d opened the window to chuck out some paper and an old yellow bus at the very last minute veered purposefully across the road towards us, a dozen male faces, swarthy, avid, were suddenly staring into mine, and they would have forced us off the road, but I let them have it through the open window, blasting their windscreen, windows, faces. The noise inside our car was like armageddon as we swerved and screamed across the tarmac and Briony wrenched the steeringwheel back just in time.

I could kill people, and not feel ashamed.

I grew closer to Luke, slowly closer. I think he began to feel happier. I know he preferred this uncouth life to the terrible safety of the Cocoon.

I could be a father, as I’d wanted to be.

But I couldn’t make Briony love me. I think she liked me, she got on with me, she adored my son, she was my mate, my comrade, but she felt the force of my dogged desire and she always said no, she rejected me, kindly but firmly, Nurse Sensible …

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Ice People»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Ice People» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Ice People» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.