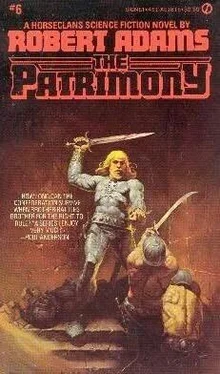

Robert Adams

The Patrimony

Sir Geros was ensconced in the privy behind his small, neat house when a scurrying servitor brought word that the tower watchers reported two armed riders approaching from the northeast. As the old warrior dropped worn baldric over his scarred, shaven head and fitted its links to those of his scabbard, he heard the first belling of the hall’s pack of hounds.

By the time he reached the courtyard, the riders were through the open gates—which laxity was as a rasp drawn across a raw nerve to the old soldier. He and the old thoheeks had always seen eye to eye on tight security for both hall and hard-won duchy, even if their ideas had differed on other points, but now Thoheeks Hwahltuh was gone to wind and neither his widow (the fat, Ehleen bitch, thought Sir Geros) nor the regent followed very many of the practices of the old lord’s lifetime.

The riders guided their big, northern horses at a slow walk through the broil of leaping, snapping dog-flesh, the second, larger man pulling along as well a pack-laden sumpter mule. As they came closer, Sir Geros could see that, under the thick overlay of dust, the scarred faces of both men were lined with fatigue. Weary too were the beasts, their heads drooping low, but the riders sat straight, their plain half-armor dented and patched here and there but polished and oiled beneath the road dust.

Polished, also, were the unadorned hilts of their broadswords and the light axes dangling from their saddlebows. The heads of the two lances socketed on the mule’s load sparkled like burnished silver in the first rays of Sacred Sun. Sir Geros did not need to examine the scabbarded sword blades to know that they too would surely be well honed and unblemished.

He knew—and respected and empathized with—this stripe of men from the days when he was a warrior and had ridden with and fought beside Middle Kingdoms Freefighters. The Sword was not only their life but their grim god—and they treated that god with respect.

As the hall servants kicked and cuffed the pack away from the mounting blocks, a groom reached for the reins of the lead rider’s stallion and nearly lost a hand for his courtesy. Big, square yellow teeth clacked bare millimeters from the jerked-back fingers.

Sir Geros detected a fleeting glimmer of soundless command—his mindspeak, for all his strivings, had never been very good—and the warhorse stood stock-still while, jackboots creaking, the wiry rider dismounted and, after hitching his sword around for easier walking, strode toward the old castellan.

A swordlength away, he halted. “Don’t you recognize me, then, old friend? Have these years of soldiering changed me that much?”

Sir Geros looked hard then. He took in the gray-blue eyes, their corners crinkled from much squinting against sun glare and the elements, the high forehead, permanently dented by the heavy helm which probably was now part of the mule’s cargo. He could see that the skin must once have been fair, but now it was weathered to the hue of polished maple, with the fine, high-bridged nose canted slightly to one side and with two large and innumerable small scars scoring the reddish-bristled cheeks.

A short, red-blond spade beard spiked forward from the man’s chin, and a thick, luxuriant mustache must once have flared, though now it was plastered to his face with sweat and dust.

The stranger had stripped the leather gauntlets from hands which were square, with a dusting of blondish hairs on their backs; the fingers were long and the nails clean and well kept. A small ruby set in carven gold adorned the least finger of the right hand—which digit, Sir Geros noticed, was missing its last joint—and the next finger bore the steel-and-silver band of a noble Sword Brother. This last proved the old warrior’s first estimation correct; this man was a sworn member of the Sword Cult.

But Sir Geros’ black eyes strayed at length back to those gray-blue ones, so like to … to hers , to those of the Lady. The Lady Mahrnee, she who had been the beloved first wife of Thoheeks Hwahltuh, and whom Sir Geros had worshiped at a distance for all the years he had served her husband.

And he knew then that, at long last, their eldest son was come to claim his patrimony.

Roaring, heedless of the dust and filth of travel, Sir Geros flung both arms about the younger, slighter man, pounding the armored shoulders and trying to speak his heartfelt welcome through tightened throat.

The riderless stallion reared, nostrils flaring. Men and dogs scattered as the big horse pirouetted on his hind hooves, the front ones lashing out, while he arched his thick-thewed neck, showed his fearsome teeth and screamed a challenge.

“Let me go, Geros!” laughed the younger man. “Steelsheen thinks you’re attacking me. Let me go before he hurts someone.”

Chuckling, the warrior strode over to the big gray, took the scarred head in his arms and gentled the beast for a few moments. Then he turned and walked back to Sir Geros, the stallion sedately trailing him.

“Has your mindspeak improved any these last years, old friend?”

The rays of Sacred Sun glinted on the shaven pate as the castellan shook his head ruefully. “No, my lord, I still can receive well enough, but …”

The younger shrugged. “Very well. Hold out your hand to Steelsheen, rub his nose, let him get your scent. I’ll tell him you’re a friend.”

When the stallion had grudgingly accepted the fact that his brother would be most wroth were he to flesh his teeth in this particular two-legs, the younger man turned about and walked back to where his companion still sat his horse.

“Dismount, Rai, I want you to meet my oldest friend.” His ready smile returned. “You know of him, even though this will be your first meeting.”

“At the captain’s command,” was the crisp reply.

The big-boned, broad-shouldered, long-armed man hiked a leg over the high, flaring pommel of his warkak, slid easily to the flagstones and walked to meet them with the slightly rolling gait of a veteran cavalryman. His bushy, chestnut brows met over a thick, slightly flattened nose. Across the front of his corselet was painted the device which signified his rank, that of troop sergeant. And Sir Geros noted that the left gauntlet had been altered to encase a hand lacking two fingers.

When the sergeant came to a halt, the captain said, “Rai, this is Sir Geros Lahvoheetos, vahrohneeskos —that’s ‘baronet,’ as we would say it—of Ahdrahnpolis.”

The sergeant swept off his broad-brimmed travel hat of soft felt and grinned widely, bowing easily for all his binding armor and clumsy boots. “Now this be a true pleasure, my lord baronet. It’s right many a long, weary mile I’ve rode a-singing the songs of yer noble deeds.”

Sir Geros’ fleshy face encrimsoned, whereupon the young officer laughed merrily and clapped a hand on the shoulder of each of the men. “Rai, you embarrass Sir Geros; he’s a very modest man, for all.”

“Geros, know you that Rai here is not only my sergeant but my friend, as well. Had he not taken me under his shield when first I went … was sent … a-warring, I’d have long since fed the crows on some battlefield. Captain Sir Bahrt of Butzburk assigned Rai to me when I was but a pink-cheeked ensign, and we’ve soldiered together ever since.”

“Since you both are my friends, it is meet you should be friends to each other.”

Wordlessly, Sir Geros extended his hand and, after a brief hesitation, the sergeant shucked a gauntlet to take it.

As hand clasped hand, Sir Geros spoke from the heart. “Sun and Wind witness that ever shall I be true to our friendship, sergeant. And may Sacred Sun shine blessing upon you for bearing Lord Tim safely back to us. He is the hope and salvation of this duchy, and there are those here who do love him.”

Читать дальше