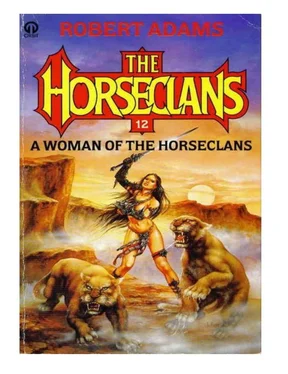

Robert Adams - A Woman of the Horseclans

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Adams - A Woman of the Horseclans» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Woman of the Horseclans

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Woman of the Horseclans: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Woman of the Horseclans»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Woman of the Horseclans — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Woman of the Horseclans», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bettylou would never have believed just how quickly the large yurt could be broken down to its components of felt, canvas, leather and wood and packed upon the largest of the three carts, which was drawn by four, rather than two, horses.

As for the chests, most of them were strapped onto packhorses, while the two smaller carts were used to transport sacks and bags, barrels and kegs and water skins, tripods and kettles and odd-sized or -shaped impedimenta.

The last night on the old campground was slept, what little sleep there was for the adults, under the stars, and with the first light of false dawn, the rugs and coverings of each individual were rolled up tightly, bound into shape, then tucked into odd spaces in the cartloads or strapped behind saddles.

The slow-moving herds had been started on the trail three days before the scheduled departure of the carts and wagons, which droving took the services of almost all of the older children, for numbers of sheep, cattle and a few goats had been taken in raids on the eastern tanning communities while the clans had camped here and these supernumerary animals would serve to help to feed both folk and cats in the hard, cold days of winter-coming when game was scarce or unobtainable.

Accustomed as she was to farm wagons, Bettylou was still mightily impressed by the four ponderous wagons each of which bore the effects of a chief (including the cat chief) and his immediate family. Each of them cleared almost two cubits off the level ground, the high-sided bodies riding on wheels six feet or more in diameter. Like the carts, the bodies were close-joined and chinked watertight and, she had been informed, could float across rivers just like boats when necessary during treks.

Three of these wagons were each drawn by eight span of huge, lowing oxen, The other. Chief Milo’s, had as motive power six pairs of brawny mules.

As the Sacred Sun’s first rays emerged from the pinkish eastern haze, whips cracked and the wheels began to turn on the axles of wagons and carts. Bettylou Hanson turned in the saddle of her mare to look back at the bare, trampled, dusty stretch of ground on which the camp had stood and thought of how much had happened to her there, of how much had changed, changed for what was assuredly the better.

Farther on, she turned and looked back again, shading her eyes, wondering if she would ever again see, would ever again be upon this patch of prairie.

Although she could not then know it. she was to see, to be upon that patch of prairie again. But it was to be many, many years later, and the woman who would then look out of those blue eyes would be changed past anything that the girl, Bettylou Hanson, could have imagined.

VII

No sooner had a spot been agreed upon for the winter camp, the yurts set up and the most absolutely pressing other necessary things for living done than every nomad not on herd guard set out with sickles and axes to the high-grass areas and the nearest forests to hack down the tough, wiry grasses and fell tree after tree.

An endless parade of carts bore the grasses to central sites within the environs of the camp, where the loads were arranged in thick, high stacks to provide food for the horses when the snows were too deep for the creatures to reach such frozen herbage as might lie beneath. If it seemed that there would be enough, a small amount of the precious grass hay might even go to the cattle and the sheep. But only a few of these were ever expected to survive a winter this far to the north, in any case, herds would be rebuilt through raiding in the following spring and summer months.

The felled trees were trimmed of branches and dragged to the campsite by spans of oxen, while the larger branches were themselves trimmed, piled onto carts and thus trundled back to add to the growing heaps of wood—wood for fuel, wood for strengthening and insulating the yurts against the coming wind and cold, wood for countless other purposes.

And every day the younger children took carts out to the pasture areas to bring them back loaded with dung—cattle dung, sheep dung and horse dung, plus the droppings of any wild herbivores they chanced across during their trips. This manure was set out carefully to dry on racks made of woven branchlets suspended over a very, very slow and smoky fire and all covered by a makeshift, temporary roof. This structure was situated some three hundred yards from the nearest yurts, in a breezy area and well downwind; nonetheless, her every visit to the latrine pits exposed Bettylou to a stomach-churning reek of the curing dung.

Therefore, she remarked to Ehstrah and Gahbee when they met one morning in the steam yurt. “Whoever thought up that abomination of spread-out dung over on the downstream side of camp knows little about manuring. It should be dumped in a pit and allowed to ferment through the winter, covered in straw.”

Ehstrah laughed and shook her head sending a rain of droplets from her streaming face. “Oh, my dear little fledgling Horseclanswoman! Behtiloo, those cowpats and sheep pellets and horse biscuits aren’t for dunging soil; Horseclansfolk don’t plant and reap crops, that’s for the damned Dirtmen.

“No, we gather and dry out dung for winter cooking fires. Hasn’t that damned, conceited, overproud Lainuh taught you anything?”

“But … but … then what are all those trees being felled for?” questioned Bettylou. I thought they were for winter fuel.”

“They are … among other uses,” Ehstrah nodded. “But you can be certain that that wood will not be used for cooking in the yurts so long as, a single dried cowpat is left to be so used.”

“Why?” asked the girl puzzledly. “You and all the others I’ve seen have been using wood as long … well, as long as I’ve been living with you.”

“Yes, that’s true, Behtiloo, but you have only lived with us in good weather, warm weather, when the sides are removed from the yurts and the tops often partially rolled up or at least gapped widely, making dissipation of smoke no problem.

“But imagine you how it would be to cook with a wood fire inside a yurt that not only has sides and top firmly closed, save for a peak-hole of the smallest possible size, but has been reinforced with wood and leather and anything else that’s available to make it as weather- and air-proof as possible. In a yurt like that, you’ll learn quickly to appreciate the true benefits of cooking with dried dung rather than with wood.

“Child, dried dung burns every bit as hot as wood, but it is almost smokeless in the burning, This relative smokelessness makes it far safer, as well, for night-long- warmth-fires in a yurt, for more than a few nomads have smothered to death on wintry nights of the smoke from their fires.”

“Uncle Milo tells the tale,” put in Gahbee, “of nearly an entire clan that died thus, years agone, in a low cave they had walled up with stones and plastered with clay for a winter home.”

Bettylou paused, then asked a question that had for long puzzled her. “Why do you and so many of the others call Chief Milo ‘Uncle’? And why has he no children or grandchildren or any other blood kin?”

Ehstrah answered, “Behtiloo, Milo is called Uncle because that is what he has always been called. Our parents called him that, their parents called him that and their grandparents and their great-grandparents back to the very beginning of the clans. He, Milo Morai, it was in fact who succored the Sacred Ancestors, led them from the Caves of Death and the waterless lands to the high places and showed them how to live a good, free life. Milo it was who forged first the links between us and the cats and, later, our breed of horses.

“When, long ago, the clans were much smaller and lived all together or, at least, not very far distant one clan from the other, Milo lived with them, guided them, advised them in composing the Couplets of Horseclans Law. Now he travels from area to area, living a year with this clan, the next year with another clan. He and I and Gahbee and Ilsah, we will winter here, then we will move on in the spring and join with another clan for the summer and autumn and winter.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Woman of the Horseclans»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Woman of the Horseclans» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Woman of the Horseclans» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.