There was a little girl lying on the blanket in front of Rae. She was about five years old and she had long auburn hair. She blinked at Rae. “Am I in heaven?” she asked.

Rae smiled at her through tears. “Could be,” she said. “I don’t know.”

“What’s your name?”

“My name’s Rae.”

“I was in the sky,” Elżbieta said.

Rae wiped her eyes and looked for Alice, but she was nowhere to be seen. All the other lunatic avatars seemed to have gone, too. As she sat there, she felt a cool breeze brush her cheek, a breeze from the River blowing away the mad greenhouse air as the invisible shield over Hyde Park lifted away into nothing.

“I was in the sky,” Elżbieta said again. “And a beautiful lady was there.”

“I’m sure there was, my sweet.”

“Are you an angel?”

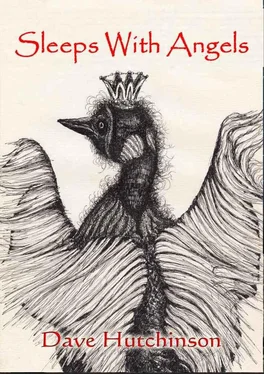

Rae laughed. “No. No, I’m not.” She stood and took Elżbieta’s hand and helped her to her feet. “But I met an angel once. Would you like me to tell you about it?”

The little girl nodded, a look of almost comical seriousness on her face. Rae draped the blanket over her shoulders and round her body and took her hand again. “It’s a long story,” she began, “and it started a very long time ago. Or perhaps it didn’t…”

They walked away, hand in hand, and as they walked tiny white flowers blossomed in their footsteps.

v

As with a lot of my stories the title came first, and the idea of nanotechnology which powers itself by metabolising blood sugar sort of popped up out of that. I’d always wanted to tackle a ‘cosy catastrophe’ story. It’s also the only story of mine, off the top of my head, that has a female protagonist. As a bit of an experiment, I self-published it as an ebook on Amazon along with another story, and eventually, after a couple of years, was rewarded with a cheque for twenty-five quid, which I regard as a bit of a win.

I was living in Gdansk back then, in a newish block of flats overlooking the harbour just outside the Old Town. In the mornings I could sit on my balcony and eat breakfast while the fake pirate boats took tourists downriver to take photographs of the old fortifications at Westerplatte. Evenings, I could wander through Hanseatic splendour, take my pick of hundreds of remarkably fine restaurants, walk the short distance to the concert hall to attend a performance by the Baltic Philharmonic, visit art galleries, catch a film. Good times, and I took it all for granted.

These days, I don’t really live anywhere. Or rather, I seem to live everywhere . In every town I visit, every city, every one-horse hamlet, a welcome is waiting for me. Hotels throw their doors open to me, private citizens unroll the red carpet. I haven’t had to pay for a meal or a night’s lodging in almost eight years. The clothes I wear, the car I drive, the cigarettes I smoke and the beer I drink are all gifts, pressed on me by a populace either eager to curry favour or to express its gratitude. You’d think it would become wearying, but you’d be wrong; there is nothing in this world better than never having to pay for anything ever again. And trust me, having people hanging on your every word, your every opinion, never ever gets old.

On the other hand, I’m on the road all the time. I have no choice. If I didn’t go to them, they would come to me, and that would become wearying.

Back then, I had a little architects’ practice. The first wave of post-Communist rebuilding in Poland had crested, and a lot of ambitious, hungry little firms were following it up. There were a lot of neo-Hadid public buildings going up, and down in Kraków it seemed as if every other office block had been presided over by the spirit of Norman Foster.

In Gdansk we were, I thought, a little more original, although there was a fashion for Baltic Baroque, bits of architecture looted from up and down the coast. I’d designed some of those buildings myself, and been paid handsomely for them. And when I drove past them I knew those hungry, ambitious little firms were already planning for the next wave, because that was what I was doing too.

I don’t design buildings any more. The world is full of architects these days, most of them completely talentless but all of them supremely enthusiastic . And that… that does become wearying.

Ten years ago, on the morning that Marcin walked into my office and invited me to the party, I was working fourteen-hour and sometimes eighteen-hour days in order to get ahead and stay ahead. I was still young. I reasoned I could maintain this for a few years, build myself a healthy bank balance and a healthy reputation, then take my foot off the accelerator a little and enjoy my life.

It was ten to eight in the morning and I had already been in the office for more than an hour when I looked up from whatever it was that I was doing — I’ve forgotten what — and saw a familiar bulky figure with tousled sandy hair talking to Agnieszka, our receptionist.

I got up from my desk and walked across the office, and as I approached the figure looked up from speaking to Agnieszka and grinned at me. “Hey, Jarek,” he called when I was still only halfway across the office. “Want to go to a party tonight?”

At school, Marcin had been one of those big soft boys who seem designed by Nature for the express purpose of attracting bullies. The first time I ever saw him he was eleven years old and two thirteen-year-olds were beating him up in the playground for no other reason than it was fun. I was on my way to a history lesson and I was two days short of my fourteenth birthday and this unknown fat boy’s plight was nothing to do with me and I kept on walking.

And then I stopped. I stood listening for a few moments as the two boys slapped the fat boy and I have no idea why I did what I did next.

I turned and said, “Leave him alone.”

One of the bullies, a nascent football hooligan named Franek, looked me up and down and said, “Fuck off, Jarek.”

I turned to face them properly. Franek’s companion was a near-imbecile named Piotr who had only just been allowed back to school after being excluded for beating up another boy. I said, “Leave him alone,” again, and Piotr gave me a ghastly expectant grin.

I wish this little tale had a happy ending, but I spent the next three nights in hospital with broken ribs and a suspected concussion. On the other hand, Franek and Piotr were never seen at school again and the day I left hospital Marcin was waiting for me outside with a shopping bag for me full of CDs and DVDs he’d pirated from the internet.

“You work too hard,” Marcin told me.

“What?” I said.

“I said you work too hard!” he said in a loud voice that I could barely hear over the party’s sound system.

I shook my head. “It’s only for a little while.”

“What?” he said.

“Oh, for —” I grabbed him by the elbow and steered him through the people crammed into the flat. The flat wasn’t very large, but a surprising number of people seemed to be here. The sound system was pumping out death metal and someone had filled the bath with ice and bottles of beer and vodka and the party was full of people like… well, like me, actually. Young professionals, comfortably-off, letting off steam. Parties like this were called ‘hit-and-runs’; many of Gdansk’s elderly Soviet-era blocks were almost empty, the residents moved to other developments and the buildings awaiting demolition. A shell company took out a short-term lease on a flat, enormous amounts of alcohol and recreational drugs were moved in, and for one night only it was party, party, party. If anyone bothered to complain about the noise and the police bothered to turn up it would transpire that no one at the party actually lived at the flat, and further investigation would reveal that the shell company which had rented it had already been dissolved and its principals had never existed anyway.

Читать дальше