“Cleans?” Growl asked. “Cleans what?”

“The dishes. The house. Clothing. For instance.”

Growl gnawed at her shoulder again, bored with the subject. “Go ahead, if you want.”

Thrush felt as if she had been slapped in the face. They expected her, the king’s wife, to sweep the floor and scrub the dirty dishes? She sat all morning staring at the filthy hearth, with its mounds of dirty bowls and spoons, the buzzing flies, the piles of bones and discarded salmon skin black with swarming ants. Fury and disgust vied for the upper hand. All the grizzly people departed the house except for her and Growl, who seemed to be the designated wife-watcher. Growl curled up on a filthy mat and did nothing but scratch herself occasionally, and doze, eyes half-open.

At last Thrush could stand it no longer. I’ll just pick up the salmon bones, she thought. It’s not right for them to sit there, and it’ll help keep the ants out. She limped over to the hearth and, slowly and awkwardly, collected all the bones and bits of rotting salmon skin. She carried the remains out to the stream and spilled them in the water, the proper way to treat the remains of the Bright Ones. Growl woke long enough to come to the door to keep an eye on her.

When Thrush returned inside, she couldn’t help but start on the dirty dishes. It was utterly disgraceful, the wife of a king of the First People washing spoons. But if she didn’t do it, it clearly wouldn’t get done. These grizzlies didn’t care what kind of filth they wallowed in. And she couldn’t live like this.

By late afternoon she had washed every dirty box and bowl in the house. She had shaken out the mats and furs in her new bedroom, discovering multitudes of fleas, and she had cleaned the furs with old and pungent urine from a long-unemptied chamber pot. By that time she had grown light-headed from hunger and was feeling very sorry for herself. The claw wounds from yesterday were becoming more and more stiff and painful with every minute. Thrush made one final trip outside to break off spruce branches for a broom, and then stopped, staring down at the clear, sweet water of the rushing stream. Sunlight flashed in the water, once, twice, a flick of the tail, a leap through the air: the Bright Ones, salmon, emblem of hope.

All of a sudden a series of intensely sharp images descended on Thrush: Rumble, earnest and lovelorn; her tall, strong older brothers, bronze-skinned, black-haired; intense, clever young Otter whittling at a trap stick, his adoring dog at his feet; silly little cousin Winter; her mother, regal and lovely in her painted hat and raven’s-tail robe. And last of all, her father the king, leaning heavily on his staff, frowning at her. He would be proud, she told herself, to learn that she was married to a king of the First People.

She wanted them all so badly. She would never see them again, and they would never know what happened to her. She was beyond the mortal realm. Her father would hire wizards to search for her, but who was sufficiently wise and powerful to find his way to the country of the First People?

Thrush tried without success to blink away her tears, and turned toward the house again. She had been trying not to notice the old woman all day. Now she could not help but look, because the old woman shifted position on the ground, and the wrinkled root of flesh stretched and heaved like a living organ. Thrush averted her eyes once more and walked as swiftly as she could toward the door.

Toward evening the inhabitants of the house began to return, bringing firewood, baskets full of berries, fish. Soon boxes were boiling away by the fire and the delicious smell of poaching salmon filled the air.

Thrush’s stomach rumbled painfully. Growl sniffed at her shoulder. “Aren’t you going to eat something?”

Thrush managed not to flinch from that damp nose. “I’m not hungry.”

Nose thrust a bowl of hot, steaming salmon at Thrush. “Fucking is hard work,” she said. She grinned coarsely. “You’d better eat to keep your strength up. Brother will want to fuck when he comes home.”

Thrush shook her head, but her stomach rumbled again. The two kept staring at her. Nose set down the salmon in front of Thrush.

“What a wonder,” said Growl, at last. “She doesn’t shit, and she doesn’t eat, either.”

“She doesn’t need to shit if she doesn’t eat,” said Nose. “Maybe she isn’t eating because we’ll find out she was lying, hmm? We’ll find out her shit stinks just like everyone else’s.”

Thrush sat by the fire, nauseated by hunger, dreading her husband’s arrival. The house’s residents began to move from the hearthside to the beds around the walls of the house. As Growl pawed and nosed at her own bed furs, rearranging them, Thrush was shocked to see a long-armed man grab her from behind, sink his teeth into her neck, and begin humping her buttocks. Growl, however, snarled, and clouted him so hard he fell backward onto an ancient, smoke-blackened raven box. He crawled back toward her, and squatted, warily, while she finished with the furs.

Then Growl looked up, and for a moment their eyes met. The man took a step forward so he could sniff at her crotch. She clouted him again, only this time she pushed him down on the furs beneath her. He grabbed at her, and, snarling and roaring and biting, they rolled and crashed together into the wall of the house. Boxes tumbled and fell to the floor. For a moment all Thrush could see were flailing limbs, and then they came up again on all fours, stark naked. The man wrapped his arms around Growl from behind. She snatched at his huge hard prick and pulled it between her legs, jamming it all the way inside of her. The two of them rocked and writhed. More boxes tipped and crashed. One of them spilled eagle down across the floor like an avalanche of snow. Thrush finally managed to avert her eyes, and then noticed, to her shame, that despite the din, no one else was paying the slightest attention.

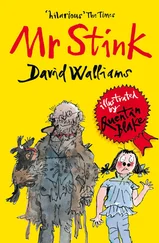

Stink arrived shortly thereafter, heralded by the shouts of the house-posts. Once again he did not bother to dress himself after shedding his grizzly mask.

Thrush preceded him docilely into the bedroom, where events went much as they had the night before. The inflamed gouges on her back and the bites on her neck and shoulders throbbed so intensely it took her mind off the other things. When he was done, he flopped down half on top of her, and she gasped and whimpered involuntarily. That made him nose at her back, sniffing, and then he began to lick the wounds with a coarse, warm tongue. She held herself rigid, filled with disgust, until he finished, and then she lay there, unable to sleep. What she could not get out of her head was the memory of Growl, naked, sweat-slicked, ecstatic with passion, pushing herself along her husband’s prick as though it were the very last moment of her life.

Thrush awoke in the morning, starving, with a picture of her father’s fish trap in her head. It couldn’t be that hard to make, she thought. She had never made one, but she could twine baskets so fine they held water, and what was a fish trap but a big, loosely woven basket weighted down on a stream bottom?

She asked Growl for a hatchet.

“A hatchet?” Growl said. “A hatchet? What do you want that for?”

“I want to cut cedar withes for a salmon trap.”

As on the previous day, Growl stared at her for a long moment before saying, “Oh.”

Growl rummaged through the boxes again, pulling out a kelp bottle full of angrily buzzing wasps, an exquisitely painted spruce-root hat, and a single enormous tail feather, white like an eagle’s but four times as large. The hatchet she finally handed to Thrush was made of polished deep-green jadeite, and hafted with pale maple wood carved all around with eyes.

Читать дальше