• Increased heart rate

• Increased blood pressure

• Increased respiration

• Imperviousness to pain

• Increased strength (followed by a drastic drop)

• Increased speed

• Drastic loss of fine motor skills

Psychological Responses

Some of the most interesting (and challenging) responses to a violent, stressful encounter are psychological. Here are some of the more common:

Tachypsychia—literally, tachypsychia means “speed of the mind” and it refers to the brain’s ability to perceive the passage of time under stress. In highly stressful situations, the brain kicks into high gear, absorbing information at a rapid pace. The result is that things seem to move in slow motion, even though you (and your opponent in a fight) are probably moving very fast. It’s also possible for tachypsychia to happen in reverse, so that a surprised victim of assault is shocked by the speed with which events occur.

Tunnel vision—the brain becomes focused on the threat to the exclusion of all else. Peripheral vision is impaired or entirely absent and one appears to be looking down a tube or tunnel. It takes an act of will to see anything outside of this field of vision. As far as survival instincts go, tunnel vision is beneficial because it focuses the mind on the immediate threat. However, it can be a problem if you’re dealing with multiple attackers or an unpredictable environment.

Auditory exclusion—or, if you prefer, “tunnel hearing.” It’s the aural version of tunnel vision. The mind shuts out anything that does not seem to be pertinent to immediate survival. The drawback to auditory exclusion is that you may not hear allies yelling at you to watch your back, or to run.

Cognitive dissonance—a fancy phrase for confusion. The brain remembers events out of sequence, and small details (the color of shoe laces, the part in someone’s hair) take on great importance while major details (the type of handgun used, the color of eyes, the license plate of a car) recede and disappear.

Denial—the brain simply refuses to acknowledge the danger (this is akin to the “freeze” response mentioned in a previous footnote) or shuts down in the face of imminent injury.

These reactions are instinctive. They’re hard-wired into our bodies and no amount of training will completely remove them. However, effective training methods can reduce the harmful aspects of these phenomena (such as auditory exclusion, denial, etc.) and improve the beneficial byproducts, such as tachypsychia (things seem to slow down to a manageable rate of speed). Training can also increase fine motor skill performance as the body learns to adapt to the “adrenaline dump” associated with a violent encounter.

Training Methods to Improve Responses

Proper training drills acclimatize the practitioner to the physical and psychological stress of a violent encounter. Of course, no training drill can safely replicate the danger and stress of a real, life-threatening situation. However, we can create drills that simulate those sensations to a lesser degree or drills that create one or two aspects of stress. For instance, take tunnel vision and auditory exclusion. It’s relatively easy to create drills that simulate stress, and then require students to deal with the immediate danger while also remaining aware of their surroundings.

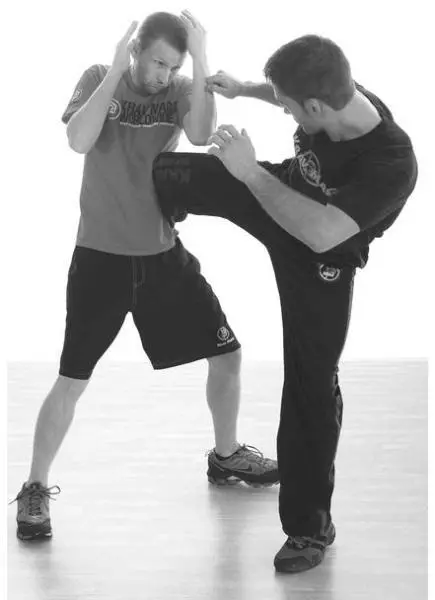

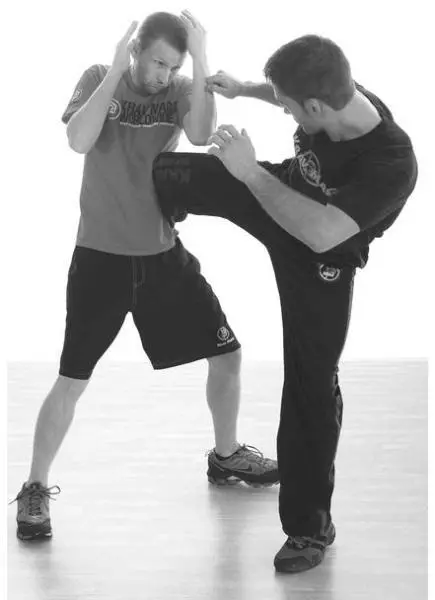

Example 1: For this drill, you’ll need three people (one defender and two attackers) as well as one training shield. The defender will need to know basic combatives, as well as at least one self-defense technique (say, for example, Choke from the Front, page 132). The defender stands in a neutral (unprepared) position with eyes closed. The attacker with the pad moves to a new position after the defender has closed his eyes. The empty-handed attacker attacks with a Choke from the Front. The defender must react efficiently and aggressively, while also scanning the room for the other attacker. Once that attacker approaches, the defender pushes away from the original attacker and deals with the new threat.

Note: Beginners will have a tendency to sacrifice the power and effectiveness of their counterattacks in order to watch for the second attacker. This is not allowed! The defender must learn to counterattack explosively to neutralize the first attacker and also be aware of the environment.

Example 2: To train away from auditory exclusion, we do many stress drills during which students must listen for a command, either from the instructor or from their partner. The action itself is incidental—it can be something as simple as turning and sprinting to the other end of the room and then coming back, or as complicated as listening for a specific set of movements such as a new punch combination, running to one of several new areas of the room, etc. It is the cognitive act of hearing and acknowledging, while still dealing with the immediate threat, that is vital.

Example 3: To acclimatize new students to the sensation of being hit and continuing to fight, we do simple drills wherein they must continually punch a pad while a third person slaps and strikes them. These strikes are light at first so that beginners don’t shut down, but as the student becomes used to the contact, the power is increased to a manageable degree. It’s not pleasant, but it’s more desirable than being shocked by the sting of a blow during a real fight.

Again, none of these drills are the same as a real violent encounter, but they do simulate various aspects of a real fight. We’ve had law-enforcement officers tell us, during some of our more extreme drills, that the emotional reactions they experienced during our drills were the same as they experienced during firefights while on duty. The more they can train under these circumstances, the more effective they’ll be during a real encounter. This sort of training will save their lives, or the lives of someone near them.

Visualization

As you undoubtedly know by now, you won’t find anything “zen” in Krav Maga. We don’t meditate, or find our center, or work on our chi . There’s a place for such things in one’s life, but you won’t find that place inside a Krav Maga school.

There is, however, some value in the idea of visualization. Visualization is simply the act of playing out a scenario in your head. See it as clearly as you possibly can. Imagine every detail—not just the attacker’s face, but his expression; not just the type of attack, but the angle of his arm, the size of his hands, etc. See yourself making the defense. You are, in effect, training your brain to tell your body to react with the appropriate defense based on the situation. We can’t all spend every day at the training center. But using basic visualization techniques, you can double or triple your training time. Having trouble with a headlock defense? Visualize doing it correctly a hundred times. You’ll find yourself improving your actual physical technique as well.

But there’s more to visualization than just the improvement of physical movement. There’s a psychological aspect as well. We fear what is unfamiliar to us. Visualizing violent encounters helps us to “know” them (at least a little) before they happen. We create the opportunity to reduce our fear of that critical moment by dealing with it in our minds first. Familiarity reduces stress. Reduced stress leads to shorter reaction time, which means we are ultimately training ourselves to react more aggressively and decisively to neutralize the threat.

Читать дальше