Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What hard evidence do we have that baking soda really works, at least for odors? None that I know of. But here’s the theory.

Baking soda is pure sodium bicarbonate(NaHCO 3), also known as bicarbonate of soda. It reacts with both acids and bases, that is, with both acidic and alkaline chemicals. (The bicarbonate ion is amphoteric .) But it is more than twenty times as effective in reacting with acids as with bases. And thereby hangs the odor-eating theory. Should a wandering molecule of a smelly acid alight upon a surface of baking soda, it will be neutralized, turned into a salt (shades of Lot’s wife!), and trapped permanently. True enough. There is no arguing with the fact that baking soda will gobble up acids—if given the opportunity. But there’s the rub, or rubs. How do we get the acid to come into contact with the baking soda, and why do we want to trap acids anyway?

First, why are acids the alleged stinkers? It goes back mostly to spoiled milk. In the old days of undependable refrigeration, and especially before pasteurization, milk quickly spoiled, not only by bacterial growth but by its butterfat breaking down into fatty acids, primarily butyric, caproic, and caprylic acids. Butyric acid is largely responsible for the odor of rancid butter, whereas caproic and caprylic acids are named after what they smell like: caper is Latin for goat. Get the drift?

So if you are in the habit of leaving month-old milk in the refrigerator for several weeks while you visit your time-share, many of the sour fatty acid molecules may indeed find their way to an open box of baking soda, fall in, and be neutralized.

But not all smelly molecules (smellicules?) that can pollute your refrigerator’s air space are acids, or even bases (alkalis) for that matter; chemically speaking, they can be virtually anything. Claiming that baking soda absorbs “odors” generically is stretching the truth by a chemical mile.

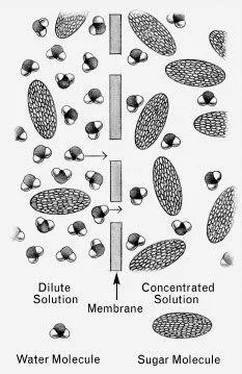

Let’s put it this way: An odor is a puff of gaseous molecules floating through the air to our noses. Each type of molecule has its unique chemical identity and its own unique set of reactions with other chemicals. No single chemical, sodium bicarbonate included, can claim to react with and deactivate any and all gaseous chemicals that happen to smell bad.

Even for acidic odors that are bicarbonate’s main quarry, note that the landing pad for a smellicule on a box of baking soda is a mere 7 square inches (the box-top area) located at some random position within a 20-cubic-foot (35,000-cubic-inch) refrigerator air space. That’s not a very efficient system for capturing smellicules. The box does not attract odors, as many people believe. It has no come-hither power, in spite of its toplessness.

The new “contraption” you saw is Arm & Hammer’s creatively spelled Fridge-n-Freezer Flo-Thru Freshener, a standard one-pound box of baking soda with removable sides, intended to give gaseous molecules more access to the baking soda by “flo-ing thru” porous paper inner seals. That sounds like a great idea, but this box, “specially designed to expose more baking soda than any other package,” uncovers only another 7 square inches of baking soda surface. And the air in the fridge doesn’t “flo thru” the package anyway. There is no fan or other force blowing it into one side of the box and out the other. Nice advertising concept, though.

In short, as it says on Arm & Hammer’s website, “Arm & Hammer Baking Soda’s deodorization power is legendary!”

I agree. It’s a legend.

What about the odor molecules that baking soda won’t absorb? There is only one common substance that can gobble them all up indiscriminately: activated charcoal. It works not by trying to be a chemical for all seasons, but by using a physical stickiness that is essentially chemistry-blind. If gases find their way into its enormous interior network of microscopic pores, they stick by a phenomenon called adsorption, the adhesion of molecules to a surface by means of what chemists call van der Waals forces.

Charcoal is made by heating hardwood, nutshells, coconut husks, animal bones, or other carbon-containing materials in an oxygen-free environment, so that they don’t actually burn, while substances other than carbon are driven off. It is then “activated” by being treated with very high temperature steam, a process that removes any remaining noncarbon substances and results in an extremely porous microstructure within the charcoal grains. A single gram (one twenty-eighth of an ounce) of activated charcoal may contain up to 2,000 square meters (18,000 square feet) of internal surface area.

You may be able to find activated charcoal (the best kind is made from coconut husks) in a drugstore, hardware store, appliance store, or pet shop. Spread it out on a baking pan with sides, and leave it in the offending fridge for a couple of days. Do not use charcoal briquettes; they contain coal, sawdust, and other substances, and their charcoal content wouldn’t work anyway because it isn’t powdered or activated.

In the end, there is only one sure-fire route to a sweet, odor-free refrigerator. Three words: prevention, prevention, prevention. Seal all your refrigerated food, especially “strong” foods such as onions, in airtight containers. Check frequently for signs of spoilage, round up the usual suspects, and throw them away. Wipe up spills promptly. Clean the fridge thoroughly. Yeah, I know, but do it more often.

Oh, you say there was a power outage while you were on vacation and all your refrigerated food spoiled and you could smell it all the way from the airport on your return? Poor soul. Neither baking soda nor charcoal will help, nor will cursing the power company. Make yourself a stiff drink, go to Louisiana State University’s disaster information website http://www.lsuagcenter.com/Communications/pdfs_bak/pub2527Q.pdf, and follow the directions.

BUTTER KEEPERS DON’T

Sticks of butter stored in a covered glass butter dish in the butter-keeper compartment in the door of our refrigerator develop a dark yellow, slightly rancid-tasting skin. Is there any way to prevent this?

You probably think you’re doing everything right, don’t you? Well, the worst place to keep butter is in a butter dish, and the worst place to keep the butter dish is in the “butter keeper” of your refrigerator.

Butter dishes were invented to facilitate serving, not preserving. Because they’re not airtight, the butter’s surface is exposed to air and can oxidize and become rancid.

Butter compartments should be banned. Many of them have little heaters inside to keep the butter at a slightly warmer temperature than the rest of the fridge to make it easier to spread. But the warmer temperature speeds up oxidation of the fat.

I keep my butter in the freezer compartment, tightly enveloped in plastic wrap. Yes, it’s hard as a rock when I want to use it, but a sharp knife can whack off a piece that will warm up and soften rather quickly.

SAINTS (AND CHEMICALS) PRESERVE US!

I’ve always wondered why some foods go bad so quickly even if refrigerated, while others seem to last forever without refrigeration. Things like opened mustard and ketchup bottles can last for weeks outside the refrigerator, and cheese, honey, and peanut butter can survive at room temperature for even longer. Is there any general way to estimate how long a food will last?

Would that life were that simple! There can be no single rule that covers all the foods we consume—an almost infinite number of combinations of thousands of different proteins, carbohydrates, fats, and minerals that make up our omnivorous diet. “Going bad” can refer to the effects of bacteria, molds, and yeasts; heat; oxidation from exposure to air; or enzymes in the foods themselves. Enzymes in fruits, for example, are there specifically to hasten their ripening, maturing, and ultimate decay.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.