Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As soon as I pour the coffee, or only when I’m ready to drink it? In which case will the coffee be hotter at drinking time?

Or does it make any difference?

Idoubt that the ancient Greek philosophers spent much time on this (especially since they didn’t have coffee), but it’s a challenging question, if not an earthshaking one.

You could settle it with an accurate thermometer, but you’d have to measure out exactly the same amounts of coffee and cream into exactly the same type of cup, all at precisely the same initial temperature, etc., etc. But doing a carefully controlled scientific experiment in a kitchen has its problems, so let’s just think it out.

All other things being equal, you’d think that both methods would lead to the same temperature of the final mixture, because you’re combining x calories of heat in the coffee with y calories of heat in the cream, for a total of x + y calories in the mixture either way. (Regarding the use of the word calorie , see the box on chapter 1.)

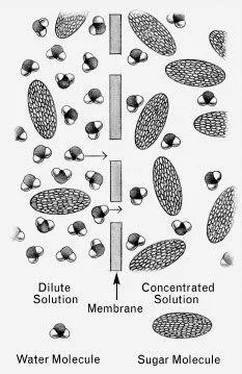

Unfortunately, according to Wolke’s Law of Pervasive Perversity, all other things are never equal. Whether it’s black coffee or creamed coffee, it must sit around until you’re ready to drink it. Meanwhile, it has been cooling off, because the air is cooler than the liquid in the cup and heat is therefore flowing from the liquid into the air. Heat will always flow from a substance at a higher temperature to an adjoining substance that is at a lower temperature.

But there are two important differences between the creamed coffee and the black coffee: (1) the cup of creamed coffee contains slightly more liquid because of the added volume of the cream, and(2) the creamed coffee is cooler than the black coffee.

Difference number 1 means that the creamed coffee with its larger volume will take more time to cool off. That is, more heat must be removed to lower its temperature by any given number of degrees. (A bathtub of water takes more time to cool than a bucket of bath-water of the same temperature.) Difference number 2 has the same result: the slightly cooler creamed coffee will cool off more slowly than the slightly hotter black coffee, because the smaller the temperature difference between a hot object and its surroundings, the slower will be its rate of cooling. So immediate creaming wins again.

My advice is to add the cream as soon as possible. The coffee will be hotter by as much as a degree or two at drinking time, and I’m sure your life will be much the better for it.

I’m pleased to report that this problem was the subject of a careful scientific experiment led by the college student Jonathan Afilalo and published in the spring 1999 issue of the Dawson Research Journal of Experimental Science . This is a most impressive journal that publishes papers on original, professional-quality research by undergraduate students at Dawson College in Montreal, Quebec.

Sidebar Science: Cooling it

THE HIGHERthe temperature of an object, the faster it will lose its heat by radiation. That’s the Stefan-Boltzmann Law. Also, the bigger the temperature difference between two objects in contact with each other (such as coffee and air, for example), the faster the hot one will lose its heat to the cooler one by conduction. That’s Newton’s Law of Cooling. There are precise mathematical formulas for both of these laws, but I see no reason to burden this page with them. I’ll return to Newton’s Law in Chapter 9.

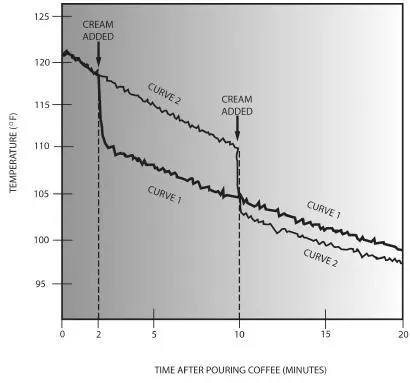

The cooling of a cup of coffee when the cream is added two minutes after pouring (curve 1), and when the cream is added ten minutes after pouring (curve 2). Adding the cream earlier yields hotter coffee at drinking time.

The students’ experiment came to the same conclusion as I did, as shown by their measured cooling curves plotted in the graph above. In curve 1 the cream was added two minutes after the coffee had been poured, whereas in curve 2 it wasn’t added until ten minutes after pouring. Note that thereafter the temperature in curve 1 remained about a degree and a half higher than in curve 2. Early addition of cream does keep the coffee hotter.

When a calorie is not a calorie

There is a difference between what a chemist calls a calorie and what a nutritionist calls a calorie. The chemist’s calorie is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one gram of water by one degree Celsius, whereas the nutritionist’s calorie, the calorie you see in diet books and on food labels, is the amount of heat energy required to raise the temperature of one thousand grams (a kilogram) of water by one degree Celsius. Obviously, then, a nutritionist’s calorie is a thousand times bigger than a chemist’s, and the chemist would call it a kilocalorie, or kcal.

In this book I find myself in the awkward position of being a chemist writing about food for an audience that spans both camps. For consistency in this book, and if my chemistry colleagues will forgive me, I will use the word calorie in the nutritionist’s sense unless otherwise noted. In many cases, I use the word calories simply to mean an unspecified amount of heat energy, in which case the chemist/nutritionist dichotomy doesn’t matter.

For those chemists who are not appeased, here is a supply of kilos to insert in front of the word calorie whenever you encounter it in the book: kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo kilo.

(Note to users of the International System of units: One nutritional kilocalorie, kcal, is equal to 4.19 kiloJoules or kJ.)

OUR ALCOHOLIC RELATIVES

I know there is ethyl alcohol, methyl alcohol, and rubbing alcohol. Which of those are edible—or drinkable—and which are not? Are all alcohols born the same before they undergo various changes or additions?

No. Even though they are members of the same chemical family, there are vast and crucial differences among the alcohols, and it can be a matter of life and death to be aware of them.

Alcohols are a large family of organic (carbon-containing) chemicals that are related in two ways: their molecules contain one or more hydroxyl groups (OH), and they react with organic acids to form chemicals known as esters.

Scientists classify everything from animals to chemicals according to their shared characteristics—characteristics that may be of no practical interest, or even downright misleading, to nonmembers of the science guild. Fret not, therefore, that eggplant ( Solanum melongena ) and potatoes ( Solanum tuberosum ) are in the same botanical family as the poisonous deadly nightshade ( Solanum dulcamara ), or that lobsters and wood lice both belong to the family of Crustacea. But don’t we all have strange relatives? Take my uncle Leon. Please. (Apologies to Henny Youngman.)

Similarly, alcohols include the highly poisonous methyl alcohol, CH 3OH, a.k.a. methanol or wood alcohol; the somewhat less toxic isopropyl alcohol, C 3H 7OH, a.k.a. isopropanol or rubbing alcohol; and the even less toxic—but still potent—ethyl alcohol, C 2H 5OH, a.k.a. ethanol or grain alcohol, the alcohol in beer, wine, and spirits. That’s not to mention alcohols that we never think of as alcohols, such as cholesterol, C 27H 45OH, and glycerol or glycerin, C 3H 5(OH) 3.(As you have noticed, chemists name all alcohols with the suffix - ol .)

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.