Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

12 flour or corn tortillas, 8 inches in diameter

Coarse salt and freshly ground pepper

Guacamole for serving

Salsa for serving

1.In a mini–food processor or blender, combine the olive oil, lime juice, garlic, and jalapeño. Whirl until smooth and puréed. Place the steaks in a nonreactive dish or zipper-top plastic bag. Spread the mixture on both sides of the steak. Cover or seal closed and marinate in the refrigerator for at least 2 hours and up to 8 hours. Return to room temperature before cooking.

2.Preheat the grill or broiler. Preheat the oven to 300°F.

3.Broil or grill the onion slices and keep warm in the oven. Wrap the tortillas in a slightly dampened tea towel, put in a pie pan or on a cookie sheet, and place in the oven to warm and steam.

4.Grill or broil the steak, turning once, for about 5 minutes per side, or less, for medium-rare. Transfer it to a cutting board and allow the meat to rest for at least 5 minutes.

5.Holding the knife at an angle to the cutting board, cut the meat across the grain into thin slices. Season the slices with coarse salt and pepper. (Coarse salt adds a nice crunch to the meat.)

6.Guests can build fajitas to their own liking. Holding a tortilla in one hand, add strips of meat, a helping of grilled onions, and a few spoons each of guacamole and salsa. Then roll the tortilla around the filling for a handheld meal.

MAKES 4 SERVINGS

PRAISING BRAISING

I’m familiar with almost all cooking methods, including boiling, simmering, steaming, roasting, baking, sautéing, frying, and grilling. Some of these methods use wet heat and some use dry heat. But I’m confused about braising, which seems to involve both wet and dry. Exactly what is braising, and what does it do that other methods don’t do?

Braising is a great vehicle for understanding both wet and dry cooking. Meat, poultry, shellfish, and vegetables are all grist for the braising mill, but I’ll limit this discussion to meats.

I like to define braising as a two-step process: browning the meat to enhance its flavor, then simmering it for tenderness. The result can be a tender, juicy, and flavorful pot roast or fricassee. Without the initial browning, a unique set of flavors can be lost. Nevertheless, many food writers define braising as the moist-cooking step alone, including Crock-Pot and slow-cooker cooking. In these cases the meat is not initially browned because the equipment isn’t designed to produce the necessary high, searing temperature. You could sear the meat in a skillet, which you then deglaze with some of the liquid to be added to the slow cooker. But that obviates one of the slow-cooker’s advantages: no pan to clean.

Call it what you like. Include the browning step in the definition or not; many braising recipes skip it, with excellent results.

The noun braise in French means “glowing coals or embers,” which were used traditionally for cooking over a brazier (and please make sure you pronounce that word with the accent on the first syllable) or for surrounding a heavy covered pot for the long, slow cooking of meats and vegetables, resulting in a carbonnade, daube , or stew. Today, we braise to conquer tough cuts of meat such as brisket, chuck, flank, round, and rump that would otherwise remain stubbornly tough and relatively un-infused with flavor.

Let’s look at the browning step first.

The traditional Irish and Appalachian folk song has it that “black is the color of my true love’s hair.” But brown is the color of many of our true loved foods. We like our meats to be browned on their surfaces and our breads to display tan or lightly browned (often romanticized as “golden”) crusts. Toast tastes better than untoasted bread; grilled steaks taste better than boiled beef. Heat-induced browning has long been used to add flavor to our foods. In the braising process, if we were to skip the initial browning step and merely simmer our meat and vegetables, we would lose much of the flavor of the final dish.

In Braising Stage One, we brown the meat by searing it on all sides in a small amount of hot oil in a heavy pot such as a Dutch oven, which we will later cover. During the searing, an intricate series of chemical reactions takes place, giving rise to the brown products. The reactions are called Maillard reactions, after Louis Camille Maillard (1878–1936), the French (obviously) chemist who characterized the initial step as being the reaction of a so-called reducing sugar, such as fructose, lactose, maltose, and glucose, with a protein.

Specifically, the initial Maillard reaction takes place between a certain part of the sugar molecule (its carbonyl group ) and a certain part of the protein molecule (an amino group in one of its amino acids). After that first step, the Maillard process continues through a complex series of both consecutive and simultaneous chemical reactions, resulting in a hodgepodge of final compounds, many of which are dark-colored polymers and most of which are aromatic and flavorful. But some of them are bitter or, unfortunately, mutagenic—they increase the risk of inheritable genetic damage.

This is where our explanation of the Maillard reactions must come to a halt, as it does in other books not intended for professional food chemists. That’s because the reactions are so complicated that chemists are still trying to isolate and identify the scores of transitional and final compounds involved. More than two hundred different chemical compounds have been isolated thus far in the products of Maillard reactions.

It would serve little purpose for me to escort you partway into the thicket of glycosylamines, deoxyosones, and Amadori rearrangements, and then leave you stranded in a sort of no-man’s-land where the trail peters out. Most chemists (and I’ll join them) simply cop out by referring to all the ultimately dark brown, nitrogen-containing compounds as melanoidins , from the Greek melas , meaning black or very dark.

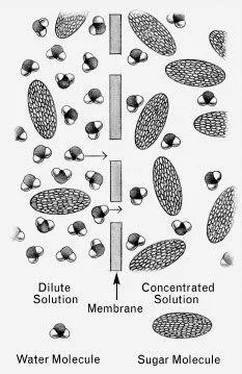

Now, on to Braising Stage Two, wherein we add a small amount of liquid—such as stock, wine, cider, or beer—to the nicely browned meat and, if we’re using them, the separately browned vegetables. Here’s where braising departs from stewing; braising uses a small amount of liquid, whereas in stewing, the meat and vegetables are completely covered with liquid. As the meat simmers in the braising liquid, the water evaporates, condenses on the inside of the pot’s cover, and drips back down, continuously basting the meat at a slightly-below-boiling temperature. This combination of heat and moisture converts one of the meat’s major proteins, collagen, into a different form called gelatin.

Collagen makes up some 20 to 25 percent of all the protein in the mammalian body. It resides mainly in the connective tissue: the sheaths that surround the muscle fibers and the tough tendons and ligaments that tie the skeletal muscles to the bones. As its places of residence suggest, collagen is what makes meats tough. But when heated for a long time in a moist environment—just what we’re doing in braising—collagen molecules undergo a change. Their triple-helical structure, looking like three braided strands of spaghetti, unwinds and breaks up into a number of small, random coils, like a bunch of tiny springs. These coils are molecules of gelatin. A much softer protein than collagen, gelatin has a prodigious ability to trap among its coils many times its own weight of water.

Evidence? The instructions on a box of regular Jell-O tell you to add two cups (237 grams) of water to only 8 grams of gelatin in the package (the rest is sugar). And yet all that water—thirty times the weight of the gelatin—is completely absorbed to form a semisolid gel when chilled.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.