Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Calling butter a fat is like calling a truffle a mushroom. Butter’s magic arises from its uniqueness, not only in its history and renowned flavor but in its composition. Butter contains a relatively large amount of water, and it’s the water that gives butter its unfatlike properties, such as being able to bring a sauce together and frothing up when heated in a sauté pan. I’ll get to these two phenomena later, but first, a little background.

Butter is a complex blend of fat (by law, at least 80 percent in the United States and 82 percent in the European Union) and water (16 to 18 percent), plus 1 or 2 percent protein (mostly casein) and, if salted, 1.5 to 3 percent salt, which both kicks up the flavor and wards off rancidity. A touch of a fat-soluble yellow-orange pigment is often added, especially in the winter, when cows of most breeds produce paler fat because their diets are devoid of carotene-rich, new-growth vegetation. The pigment, used also to color cheese, is annatto ( achiote in Spanish), from the seeds of the South American tree Bixa orellana .

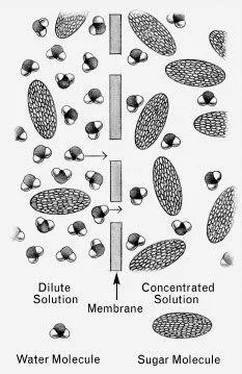

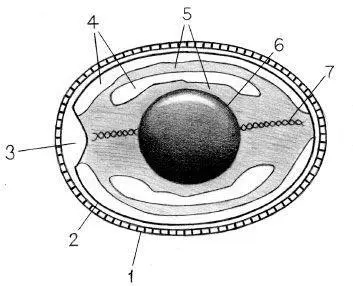

Fats and water won’t ordinarily mix. But in butter, the milk’s fatty part (the butterfat) and watery part (the buttermilk) are combined in what appears to be a homogeneous mass. On a microscopic scale, we would see that the water is in the form of tiny globules (measuring less than 0.0002 inch), dispersed uniformly throughout the sea of semi-liquid fat like so many poppy seeds in a Jell-O mold. Such a stable configuration of two liquids that won’t ordinarily mix is called an emulsion. (See chapter 8.) Butter is a water-in-oil emulsion.

Seemingly paradoxical is the fact that butter is made from cream, an emulsion with precisely the opposite structure. Cream consists of microscopic fat globules dispersed throughout a watery liquid: an oil-in-water emulsion. When cream is churned into butter, the mechanical action breaks open the surfaces of the tiny fat globules so that they can coalesce—first into rice-sized grains, and ultimately, after being squeezed and kneaded, into a continuous mass incorporating microscopic globules of water.

But, you say, butter is mostly solid fat, not a liquid oil. Actually, it is both. For one thing, in chemistry, the same word, fat , is used whether the substance happens to be solid or liquid at room temperature. Moreover, the milk fat in butter is partially in the form of a sea of soft, almost liquid “free fat” and partially in the form of solid crystals. Butters that have been churned at different temperatures and then cooled and tempered differently (much as a pastry chef tempers chocolate to control its fat crystals; see chapter 10) wind up with different ratios of free fat to crystals, and hence with different degrees of firmness, ranging from soft spreaders to bread shredders.

Enter the wee little beasties. Several breeds of bacteria, some good for us and some bad, view milk sugar (lactose) as yummy victuals and will thrive in cream if we let them. The bad ones can be knocked off by pasteurization, while the good ones can be encouraged by warm temperatures to go ahead and nosh, generating some wonderfully flavorful by-products as they do. Both of these measures have important consequences for the butter.

In the United States, all cream used to make commercial butter must first be pasteurized by being held at 165°F (74°C) for 30 minutes, a process that connoisseurs insist imparts a slightly cooked, off flavor compared with down-on-the-farm, unpasteurized butter. In the best of all possible worlds, though regrettably not very often in our part of the world, the cream will then be cultured (or “ripened,” “matured,” or “soured”) by the addition of bacteria, usually a mixture of Lactococcus and Leuconostoc strains, which produce lactic acid and diacetyl. Lactic acid adds a pleasant tang to butter, while diacetyl is the chemical that gives butter its most prominent characteristic flavor. Unfortunately, most American mass producers of butter (at up to 8,000 pounds per batch) skip the time-consuming culturing step.

By this time you have figured out that butter froths up in the sauté pan because its water turns to steam, which then bubbles its way out noisily. But in spite of its high water content, hot butter doesn’t spatter in the pan as other hot fats do in the presence of water. Instead, the butter merely foams up around the food. That’s because butter’s water is in the form of individual, microscopic globules. They don’t join together into droplets that, in contact with hot fat, would explode into relatively large bursts of steam, carrying spatters of hot fat along with them.

How, then, does butter homogenize and thicken a pan sauce? In two ways. First, butter’s fat content can absorb the fat in the pan while its water content can absorb the wine or stock, thus bringing them into a sort of matrimonial harmony. But the marriage wouldn’t last very long if the butter didn’t contain a small amount (about 0.24 percent) of lecithin, an emulsifier. An emulsifier’s molecules stabilize an emulsion by latching onto both fat molecules and water molecules at the same time, effectively keeping them together. (See chapter 9.) When the entire contents of the pan have thus become a fat-and-water emulsion, the contents will obviously be thicker, glossier, and more unctuous than the watery wine or stock alone. French chefs ever since Escoffier have been finishing their pan sauces with une noisette of butter.

THE FOODIE’S FICTIONARY:Acidophilus—the Escoffier of Greek cuisine

GOOD EGGS GET GOOD GRADES

There are so many kinds of eggs in my supermarket, I don’t know which to buy. They all seem to be Grade A, which I suppose is good, but what about size and freshness?

The USDA grades eggs according to quality—not according to freshness—as AA, A, or B. To earn a grade of AA, an egg must have an air cell within the wide end that is less than an eighth of an inch (3 millimeters) deep; a shell that is well shaped and clean, with very few ridges or rough spots; and when the egg is broken onto a flat surface, a yolk that stands up high and domelike in the center of a clear, thick, and firm white.

Grades A and B fit these criteria slightly less rigorously. They may not look as pretty when fried or poached, because the yolks may be a bit flat and the whites a bit more runny, but they are perfectly fine for uses in which they won’t be served whole.

Submitting eggs for federal grading, however, is optional for the producers (the human ones, that is, not the hens). Eggs sold in cartons without the USDA shield will have been graded according to state laws, which vary all over the lot.

If you find some eggs in a carton that don’t appear to be the same size, curb your suspicions. The USDA determines their average size by the weight of a whole dozen. The standard egg sizes are jumbo, extra-large, large, medium, small, and peewee. By the dozen, they weigh 30, 27, 24, 21, 18, and 15 ounces, respectively.

Unless they state otherwise, you can assume that all recipes, including those in this book, have been tested using large eggs. But if you have only mediums, here’s how to substitute: If the recipe calls for one, two, or three large eggs, use the same number of mediums. For four, five, or six large eggs, add one medium. Have only extra-large eggs? For one, two, three, or four large eggs, use the same number of extra-large. For five or six large eggs, use one fewer extra-large. Or, just forget the whole thing and use ¼ cup of beaten egg for every egg specified in the recipe.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.