Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Marlene Parrish - What Einstein Told His Cook 2» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, Издательство: W. W. Norton & Company, Жанр: Кулинария, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:What Einstein Told His Cook 2

- Автор:

- Издательство:W. W. Norton & Company

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Einstein Told His Cook 2: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

What Einstein Told His Cook 2 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «What Einstein Told His Cook 2», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

1 cup ketchup

¼ cup Jack Daniel’s black label whiskey

¼ cup dark molasses

¼ cup cider vinegar

1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

1 tablespoon freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 tablespoon soy sauce

½ teaspoon freshly ground pepper

½ teaspoon dry mustard

1 clove garlic, crushed

Mix all the ingredients together in a small saucepan. Place over medium-high heat, bring to a boil, and then reduce the heat to low and simmer for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally.

MAKES ABOUT 2 CUPS

…AND THEY’RE OFF!

At a Kentucky Derby Day party, my friends served mint juleps. I noticed that shortly after the host mixed each drink, a coating of frost formed on the outside of the glass. I know that a tall glass of Tom Collins, for example, will get wet on the outside, but I’ve never seen it get cold enough to freeze. What’s special about the mint julep?

Ask any dyed-in-the-cotton Southerner and the answer will be “Plenty.”

When sipped at the speed of a Southern drawl on a hot summer’s eve beneath a fragrant, blooming magnolia, few beverages are more refreshing than a mint julep—or more insidiously intoxicating, because its seductive sweetness masks the fact that it is virtually straight bourbon. But also intoxicating (to some of us) is the science behind the frosting.

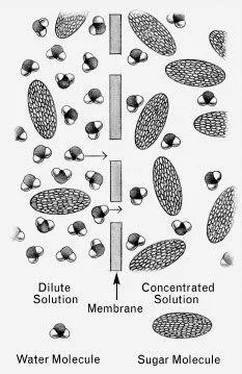

Stripped to its mundane fundamentals, a mint julep is made by mashing mint leaves with sugar in a metal mug or goblet, filling it with crushed ice, and pouring a generous glug of bourbon in. Now, if we were to add plain water instead of bourbon, the ice and the water would soon come to the same temperature: a temperature at which they could coexist without all the ice melting or all the water freezing. (They would come to equilibrium .) That temperature, as you have guessed, is the freezing point of H 2O, normally 32°F or 0°C.

But bourbon, bless its heart, contains alcohol as well as water. The alcohol (helped by the sugar) lowers the freezing point, just as antifreeze lowers the freezing point of the coolant in your car’s radiator. Because the freezing point is now lower, so is the ice-and-water coexistence temperature, which is the same. If the ice and liquid are still to coexist, they must get down to this lower temperature by melting some of the ice, a process that absorbs heat and makes the mixture colder. It’s the same phenomenon that makes an ice-and-salt mixture so cold that it can freeze cream in an old-fashioned ice cream freezer. The salt in this case lowers the freezing point, as the alcohol does in the julep.

The cooling of the goblet’s contents by the bourbon’s alcohol can be so great that on a humid day the moisture in the air will not only condense on the outside of the goblet but actually freeze there, forming a coating of frost. A Tom Collins won’t get cold enough to freeze the moisture on the outside of its glass because it may contain only a few ice cubes and not enough alcohol to lower the freezing temperature very much. In a julep goblet, however, all that crushed ice has a huge surface area at which the ice/water equilibrium can play out its temperature-lowering game on a grand scale.

For the most spectacular presentation, mint juleps should be made and served in sterling silver—not silver-plated—goblets or cups, rather than in glasses. Glass is a very poor conductor of heat (and cold), whereas sterling silver is 92.5 percent silver, and silver is the best heat conductor of all metals.

A mere Yankee, I dare not venture to present here a recipe for a mint julep, inasmuch as part of the reason the South is warmer than the North is that Southerners are engaged in perpetual heated arguments about the best way to make one. Find a Kentucky colonel (no, not that one; he’s no longer with us) and ask him.

SHAKE ’N’ STIR

I’ve been having a discussion with some friends about chilling drinks by stirring or shaking with ice cubes—how much ice to use and what the dilution factor would be. One guy said that he uses lots of ice to chill faster and get less dilution. I countered that it may chill faster, but the dilution factor would be the same: less water from each cube, perhaps, but the total amount of melted ice would be the same.

Any help greatly appreciated.

I’m with the other guy.

First, the colder the ice the better. Colder ice will cool the liquid faster, just as colder rocks would do. And melting is not necessary for cooling; cold rocks would do the job as well.

If two substances are in contact, heat will flow automatically from the warmer one into the cooler one. In this case, heat flows out of the liquid and into the ice. Or, if you will, ice sucks heat out of the liquid. The colder the ice starts out, the more calories of heat it can suck out of the liquid before it reaches its melting/freezing point of 32°F (0°C) and even begins to think about melting. So if the ice is cold enough—far enough below 32°F—there need be little, if any, melting and consequent dilution.

Second, the more ice the better. Lots of ice in the container forces the liquid into crevices between the ice chunks, creating thin layers of liquid that make efficient thermal contact with the ice surfaces and cool faster than would thicker layers of liquid. Another way of putting this is that the more ice chunks there are, the more ice surface is available for heat exchange with the liquid. So again there’s faster cooling and less, if any, melting—if you don’t leave the ice in too long. The best cooling mantra then, is “Lots of ice, short time.”

That’s ice cubes , incidentally, not cracked ice. Cracked ice has so much surface area, and the heat exchange between it and the liquid is so efficient, that it will start melting and watering down your drink before you can say Jack Daniel’s.

Unfortunately, most bartenders’ ice isn’t very cold. It has probably been sitting in the bin for hours, warming up to within a few degrees of its melting point, so it doesn’t have much cooling capacity before it begins to melt and dilute your drink.

But luckily, ice doesn’t melt as soon as it gets to its melting point. Each gram of ice needs to absorb another slug of calories—0.080 calories, its heat of fusion —in order to break down its solid structure and turn into a fluid. So even not-very-cold ice will still do a pretty good job of cooling, albeit accompanied by some melting and dilution. Just don’t let the bartender stir or (heaven forbid) shake your martini too long.

Because we do want some melting to take place in a martini (the drink will be too harsh unless it contains about 10 percent added water), one must strike the proper balance among the amount of ice, its temperature, and the length of stirring. That’s why so many people mess up martinis, which in principle should be the simplest drink in the world to make.

MIND YOUR CHEER

I’m a moderate drinker. I have a glass of wine with dinner, and in social situations I’ll often have one or two drinks. Really, that’s all. But at holiday-season parties it’s easy to lose track while nibbling and chatting, so on occasion I have imbibed a bit too much for my own comfort and, I fear, for the comfort of others as well. I know everybody’s different, but are there any guidelines for figuring out what effects various amounts of alcohol are likely to have on a person?

Having spent decades on a university campus (no, it didn’t take me that long to graduate; I was on the faculty), I have heard more than a little about what the students call “hearty parties.” Translation: binge drinking.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «What Einstein Told His Cook 2» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.