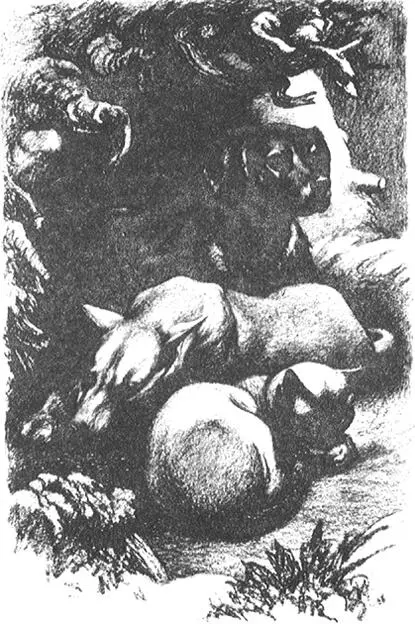

The cat walked into the library to curl up on the warm hearth. Later when the ashes grew cold he would move to the top of the radiator, and then, sometime in the middle of the night, he would steal upstairs and curl up beside the old dog. It was useless shutting the bedroom door, or any other door of the house for that matter, for the cat could open them all, latches or doorknobs. The only doors that defeated him were those with porcelain handles, for he found it impossible to get a purchase on the shiny surface with his long monkeylike paws.

The young dog padded off to his rug on the floor of the little back kitchen, and the bull terrier started up the steep stairs, and was already curled in his basket in the bedroom when Longridge himself came to bed. He opened one bright, slanted eye when he felt the old blanket being dropped over him, then pushed his head under the cover, awaiting the opportunity he knew would come later.

The man lay awake for a while, thinking about the days ahead and of the animals, for the sheer misery in the young dog’s eyes haunted him.

They had come to him, this odd and lovable trio, over eight months ago, from the home of an old and dear college friend. This friend, Jim Hunter, was an English professor in a small university about two hundred and fifty miles away. As the university owned one of the finest reference libraries in the province, Longridge often stayed with him and was, in fact, godfather to the Hunters’ nine-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. He had been staying with them when the invitation came from an English university, asking the professor to deliver a series of lectures which would involve a stay in England of nearly nine months, and he had witnessed the tears of his goddaughter and the glum silence of her brother, Peter, when it was decided that their pets would have to be boarded out and the house rented to the reciprocal visiting professor.

Longridge was extremely fond of Elizabeth and Peter, and he could understand their feelings, remembering how much the companionship of a cocker spaniel had meant when he himself was a rather lonely child, and how he had grieved when he was first separated from it. Elizabeth was the self-appointed owner of the cat. She fed and brushed him, took him for walks, and he slept at the foot of her bed. Eleven-year-old Peter had been inseparable from the bull terrier ever since the small white puppy had arrived on Peter’s first birthday. In fact, the boy could not remember a day of his life when Bodger had not been part of it. The young dog belonged, in every sense of the word, heart and soul to their father, who had trained him since puppy-hood for hunting.

Now they were faced with the realization of separation, and in the appalled silence that followed the decision Longridge watched Elizabeth’s face screw up in the prelude to tears. Then he heard a voice, which he recognized with astonishment to be his own, telling everybody not to worry, not to worry at all—he would take care of everything! Were not he and the animals already well known to one another? And had he not plenty of room, and a large garden? … Mrs. Oakes? Why, she would just love to have them! Everything would be simply wonderful! Before the family sailed they would bring the dogs and the cat over by car, see for themselves where they would sleep, write out a list of instructions, and he, personally, would love and cherish them until their return.

So one day the Hunter family had driven over and the pets had been left, with many tearful farewells from Elizabeth and last-minute instructions from Peter.

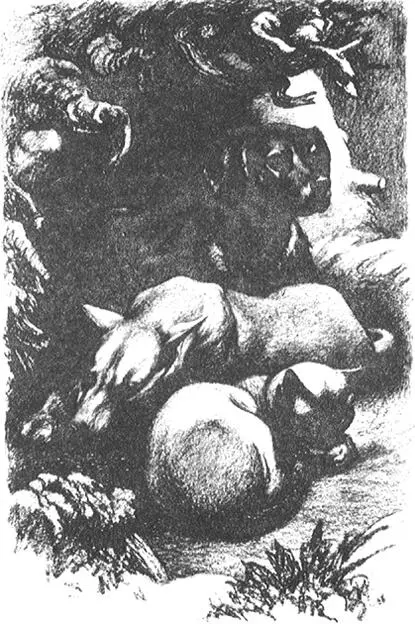

During the first few days Longridge had almost regretted his spontaneous offer: the terrier had languished in his basket, his long arched nose buried in the comfort of his paws, and one despairing, martyred eye haunting his every movement; and the cat had nearly driven him crazy with the incessant goatlike bleating and yowling of a suffering Siamese; the young dog had moped by the door and refused all food. But after a few days, won over perhaps by Mrs. Oakes’s sympathetic clucking and tempting morsels of food, they had seemed to resign themselves, and the cat and the old dog had settled in, very comfortably and happily, showing their adopted master a great deal of affection.

It was very apparent, however, how much the old dog missed children. Longridge at first had wondered where he disappeared to some afternoons; he eventually found out that the terrier went to the playground of the little rural school, where he was a great favorite with the children, timing his appearance for recess. Knowing that the road was forbidden to him, because of his poor sight and habit of walking stolidly in the middle, he had found a short cut across the intervening fields.

But the young dog was very different. He had obviously never stopped pining for his own home and master; although he ate well and his coat was glossy with health, he never maintained anything but a dignified, unyielding distance. The man respected him for this, but it worried him that the dog never seemed to relax, and always appeared to be listening—longing and waiting for something far beyond the walls of the house or the fields beyond. Longridge was glad for the dog’s sake that the Hunters would be returning in about three weeks, but he knew that he would miss his adopted family. They had amused and entertained him more than he would have thought possible, over the months, and he realized tonight that the parting would be a real wrench. He did not like to think of the too quiet house that would be his again.

He slept at last, and the dreaming, curious moon peeped in at the window to throw shafts of pale light into the rooms and over each of the sleeping occupants. They woke the cat downstairs, who stretched and yawned, then leaped without visible effort onto the window sill, his gleaming eyes, with their slight cast, wide open and enormous, and only the tip of his tail twitching as he sat motionless, staring into the garden. Presently he turned, and with a single graceful bound crossed to the desk; but for once he was careless, and his hind leg knocked the glass paperweight to the floor. He shook the offending leg vigorously, scattering the pages of Longridge’s note—sending one page off the desk into the air, where it caught the upward current of hot air from the wall register and sailed across the room to land in the fireplace. Here it slowly curled and browned, until nothing remained of the writing but the almost illegible signature at the bottom.

When the pale fingers of the moon reached over the young dog in the back kitchen he stirred in his uneasy sleep, then sat upright, his ears pricked—listening and listening for the sound that never came: the high, piercing whistle of his master that would have brought him bounding across the world if only his straining ears could hear it.

And lastly the moon peered into the upstairs bedroom, where the man lay sleeping on his side in a great fourposter bed; and curled against his back the elderly, comfort-loving white bull terrier slept in blissful, warm content.

2

THERE WAS a slight mist when John Longridge rose early the following morning, having fought a losing battle for the middle of the bed with his uninvited bedfellow. He shaved and dressed quickly, watching the mist roll back over the fields and the early morning sun break through. It would be a perfect fall day, an Indian summer day, warm and mellow. Downstairs he found the animals waiting patiently by the door for their early morning run. He let them out, then cooked and ate his solitary breakfast. He was out in the driveway, loading up his car when the dogs and cat returned from the fields. He fetched some biscuits for them and they lay by the wall of the house in the early sun, watching him. He threw the last item into the back of the car, thankful that he had already packed the guns and hunting equipment before the Labrador had seen them, then walked over and patted the heads of his audience, one by one.

Читать дальше