Not every associate was fortunate, or strategic, enough to find a rabbi, particularly one as influential within the firm as Perry. Perry was an acknowledged rainmaker, a partner who landed large corporate clients for the firm and then distributed the work to Corporate group associates. He’d noted Laura’s quick mind and rigorous approach back when she was still a summer associate, and when she was a first-year he’d made a point of routing her way the more complex of the memos and briefs first-years were expected to spend the majority of their time hammering out. Laura, who had attended Hunter College and Fordham Law in the city, noted with inward satisfaction how much more quickly she was rising than some of the Ivy Leaguers she’d started out with, although she was careful never to let her sense of her own success show outwardly.

She had come to specialize in contracts, and she was more at home among the language of contracts than anywhere else. There was something profoundly comforting in having all worst-case scenarios accounted for and resolved ahead of time, nailed down in the black-and-white precision of a signed and witnessed document. In a perfect world, Laura thought, all of life’s surprises would be anticipated and disposed of with equal ease.

It was Perry who’d decided a little over a year ago that Laura was finally ready to go to client meetings. She’d met Josh at the first of these meetings, which had lent the early days of their romance an air of the clandestine. She’d known how it would look to the rest of the firm, and to Perry in particular, if the fact that she was dating a client became general knowledge. Sometimes Laura wondered if maybe she’d agreed to marry Josh after only a few months of dating because marriage recast the whole thing in an indisputably respectable light. When she’d announced her engagement, Perry had hugged her warmly and said, “ When love is strong, a man and a woman can make their bed on a sword’s blade . May your love always be as strong as it is now.” It had sounded nice at the time, although later Laura thought it was rather more portentous than an expression of congratulations ought to be.

Now, in the face of Perry’s admonishment that she finish up for the night, Laura found she wasn’t as eager to return home as she’d been in the earliest days of her marriage, only six months ago. Sarah’s things—mostly items salvaged from the record store she’d owned and then sold sixteen years ago—remained unpacked in the boxes stored in their spare bedroom. Still, the smell of old records and yellowing newspapers, the smell of Laura’s childhood, had invaded the entire upstairs of their apartment. Even the faint odor of a litter box threatened to unearth long-buried images and associations.

This displacement between then and now created an ever-present sense of unease, like a low-frequency sound she couldn’t hear clearly enough to identify, but that was disturbing nonetheless. Laura found herself using the downstairs guest bathroom whenever possible and avoiding going upstairs to bed until the moment when she literally couldn’t hold her eyes open anymore. Even so, her sleep was restless these days, leaving her almost more exhausted when she woke up than she’d been when she’d gone to bed.

She knew how eager Josh, a self-described music geek, was to go through all of Sarah’s posters and listen to recordings of songs on their original vinyl that hadn’t been available in nearly a generation. Josh was in love with the past. Stored in their home office were stacks of photo albums and summer-camp swimming awards and school report cards and even the twenty-year-old fraternity roster listing all the names and phone numbers of his pledge class. Laura knew he was wondering why she hadn’t looked through everything yet, even though over a month had passed since they’d cleaned out Sarah’s apartment. So far, however, he hadn’t pressed the point.

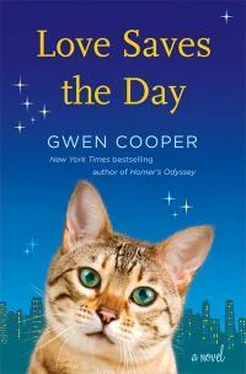

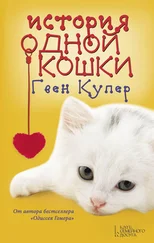

The only one who had spent any time going through Sarah’s things was Prudence. That her mother, of all people, should have decided to adopt a cat was something Laura still couldn’t understand. But it was clear that Prudence missed Sarah terribly. The cat had spent her first days with them both refusing food and vomiting, and her obvious distress had made Laura wonder if they’d made the right decision, or if perhaps Prudence would be happier living in a more cat-friendly household someplace else, despite her mother’s will. Only some deep reluctance to part with this final living link to Sarah had held her back.

At their Passover Seder three nights earlier, when Prudence had made such a mess of their carefully laid table, Laura had felt both deeply embarrassed by Prudence and deeply sorry for her. Like Laura, Prudence had been raised by Sarah. How could she be expected to understand the way normal families behaved at a holiday dinner? It had taken Laura years of careful observation as an adult to figure it out herself.

Still, it had been nice, these last few weeks, to see Prudence finally begin integrating herself into the general flow of life in their apartment. Digging out one of Sarah’s old dresses from the bag she’d salvaged from the trash room at the last minute had been the right idea. Prudence was starting to act like a normal cat again (as if, Laura thought wryly, there was any such thing as “normal” when it came to cats). Laura couldn’t help watching her, couldn’t help smiling at the way Prudence sprawled out on her back sometimes, four white paws in the air, in the patches of sunlight that fell through the windows. What would it be like, she wondered, to give yourself over so entirely to something as simple as that, to have no thought in your mind beyond, This sunlight is warm. It feels good .

Laura had noted Prudence’s fascination with the same flock of amber-and-white pigeons across the street that she found herself watching at times. Such unusually colored birds would have been prized in the neighborhood she’d grown up in, would have been kept and coddled in rooftop coops and eyed wistfully by young boys who would have tried to steal a few. Once, when she was twelve, Laura had sneaked onto the rooftop of the apartment building next to her own to cradle a young pigeon under the watchful eyes of its owner. The world before her was an uneven patchwork quilt of white cement and black tarpaper roofs, seamed by heavily laden clotheslines. Laura had never touched the warm feathers of a living bird before, never felt the intricate symmetry that molded the soft fluff into a resilient shell. The only feathers she’d touched were those found on sidewalks. Sarah had been furious when she’d found out Laura had gone onto the roof next door; two weeks earlier, a fourteen-year-old boy had plummeted to his death trying to leap from one rooftop to another.

Laura liked to watch Prudence looking out the window. At such moments, she wanted to stroke Prudence’s fur, to breathe in the cinnamon-and-milk smell of her neck and hear the low rumble of her purring. It had been a long time since she’d sat with a cat and listened to it purr, or felt the kind of peace that comes when a small animal trusts you enough to fall asleep in your lap.

But whenever she reached out to Prudence, she saw—no matter how hard she tried not to—an old man in tears, kneeling on a cracked sidewalk and crying out, She’s all I got! There was a terrible danger in loving small, fragile things. Laura had learned this almost before she’d learned anything else.

Laura knew her face must have taken on a faraway expression, because now Perry was repeating, “You should go home for the night.” And then, with a look of concern that was almost harder for Laura to bear than a direct reprimand would have been, “I wish you’d taken some time off when your mother died.”

Читать дальше