‘Well I don’t think he would be against me,’ said Pavel. ‘May I go?’ [106] Dear Comrade

Izvestia refused to publish the letter, but it did appear in the International Herald Tribune . A year later Pavel was arrested, put on trial and sentenced to exile. And now, half a century on, 4,000 miles from Dima’s cell in Murmansk, the retired physics teacher is schooling himself in the system that once targeted him, the same system (for he believes nothing much has changed) that has captured his son.

‘It is the Soviet legal machine, so to speak,’ says Pavel. ‘So I started reading the Russian criminal code – for many years I didn’t do it – and the constitution and how it’s formulated and how to fight it, and I talked to lawyers and so on. It was important, because in spite of Russia being a totalitarian state they still have to make something by law, and we had to answer every legal step. Some people didn’t understand it, but I knew. Because they once did it to me.’

Izvestia, the newspaper he wrote to in 1967 seeking justice, is still in print and is playing a leading role in the propaganda war against his son – even speculating that Greenpeace volunteers may have been responsible for beating up a Russian diplomat in the Netherlands. But Izvestia is no longer owned by the Communist Party. Now it’s owned by Gazprom. [107] http://www.rferl.org/content/article/1059107.html

Dima is standing in the doorway of his cell watching the guards lifting mattresses and looking under them, flicking through the pages of his books and peering inside jars. Then from behind him he hears a familiar voice.

‘Ah yes, Litvinov. Dimitri, how are you doing, my friend?’

Dima spins around. It’s Popov. He’s standing on his toes and looking into Dima’s cell.

‘They found anything?’

‘Nope.’

Popov nods, then almost absently he says, ‘So, you’ll be leaving us soon.’ He drops onto his heels and flashes a golden toothy smile.

Dima’s heart jumps. ‘We’re getting out?’

Popov sniffs. ‘No, no. They’re moving you.’

‘Moving us? Where?’

‘St Petersburg.’

‘ St Petersburg? ’

‘Yup.’

‘When?’

‘Couple of days maybe. For all I know tomorrow.’

‘Do you know why?’

‘Dimitri, please.’ Popov holds out his hands in a plea of false modesty. ‘They tell me nothing. You probably know more than I do.’

‘I don’t know anything.’

‘I’m sorry, I shouldn’t have said anything. Silly me.’ The governor looks down at his shoes and chews his lip. ‘No, it’s all a mystery to me. If I was to guess I’d say you’re going to be the subject of a bit of special treatment. But then, I know nothing.’

The fist in Dima’s stomach clenches. ‘What does that mean, special treatment?’

‘It means just that. Special treatment.’

‘And… what, it’s just me moving? The others, are they coming too? To St Petersburg?’

‘I would imagine so, yes.’

‘But you don’t know for sure?’

Popov shrugs, pats Dima on the shoulder and waltzes off down the hallway, running a finger along the wall as he goes.

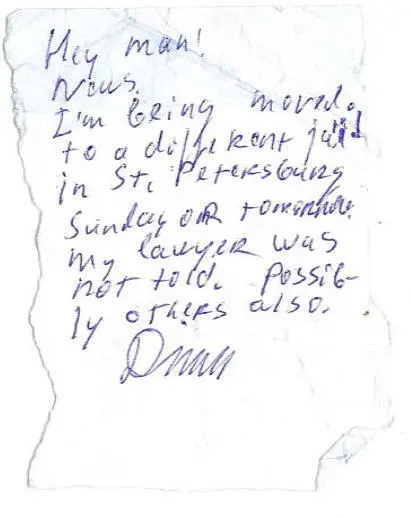

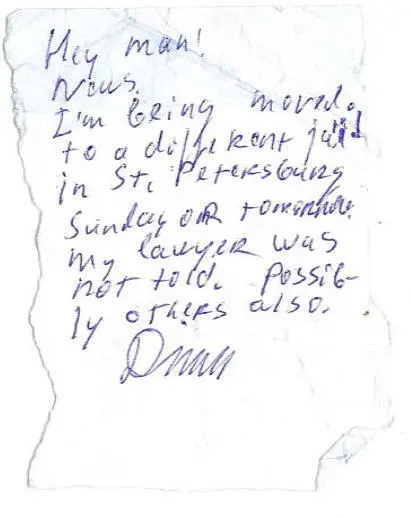

As soon as the lights are killed and the doroga is up and running, Dima gets the news out. Phil’s cellmate pulls in the sock and hands him a note. (See opposite.)

The road buzzes with the news, it’s shouted over the walls at the gulyat , it’s all anyone talks about.

‘It’s today.’

‘I heard it was next week.’

‘No, it’s definitely tomorrow.’

‘Well, you should know this,’ Roman shouts to Dima over the wall. ‘The Stolypin , it is hell.’ He uses the Russian slang word for a prison transport train, named after the tsarist prime minister Pyotr Stolypin, who commissioned railway carriages to transport revolutionaries to Siberia. ‘They are very fucking horrible. They are bad. They are very bad. It can take a month. You stay in transit prisons on the way. Tough places. We will be in a car cell with many people. Not nice people. There’s no water, it’s very hot, there’s no food. We’ll need to bring plastic bottles with us to piss. It is going to be horrible. I’ve heard about these transports.’

And Dima shouts back, ‘Come on, man. Don’t worry, we’re not even sure we’re going by Stolypin . Maybe we’ll go by bus or by plane.’

‘No, it is going to be very bad. I am not happy about this. It is bad. And in St Petersburg they have Kresty’ – the notorious prison, famous for housing political detainees as far back as Trotsky – ‘It is a tough prison. It has bad cells, poor conditions, a very strict regime. My cellmates, they say it is dark.’

Daniel Simons is terrified.

If he screws this up then he’ll be responsible for the Arctic 30 staying in jail for years. He thinks this is the only good shot Greenpeace has at getting everyone out. There is nothing he has dreaded more than appearing as a witness before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

Twenty-one eminent judges from around the world are sitting in a semi-circle in a vast Hamburg courtroom. All but one of them are elderly men. They look like a council of Jedi Knights in a Star Wars movie. And Simons is standing before them.

He and his boss Jasper Teulings have pushed for weeks for a hearing at ITLOS – the international court empowered to demand the release of the Sunrise and its crew. Now that hearing is starting and Simons is giving evidence. For the Greenpeace lawyers it looks like an open and shut case – the raid on the Sunrise would only have been legal if the Arctic 30 were genuine pirates, and by now not even the Kremlin’s spokesmen are claiming that.

The Russian government is boycotting the hearing, a move taken by observers to be an admission of the weakness of their case. Nevertheless one of the judges, Vladimir Golitsyn, is from Russia, and Simons feels he seems to be speaking for the Kremlin as he fires off a volley of hostile questions. [108] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-11-06/dutch-urge-release-of-greenpeace-crew-in-court-clash-with-russia.html

Simons reels off answers with a confidence that belies the heavy responsibility he’s feeling.

When the submissions are completed the court announces that it will rule in a fortnight. Daniel Simons breathes a sigh of great relief. He leaves the courtroom and fetches his computer. He and Teulings have one more thing to do today.

They’re still in the court building. They go to the Dutch delegation and tell them they have something that might be of interest. Simons opens his laptop and presses play. On the screen masked armed commandos abseil onto the deck of the Arctic Sunrise . Activists thrust their arms in the air and offer no resistance. Frank is chased up steps and pulled to the ground.

It’s the film from Phil, recorded on the camera card and smuggled out through a matchbox.

The Dutch delegation stares open-mouthed at the screen. They’re impressed by the intensity of it. The activists look nothing like pirates. Immediately the delegation submits the footage to the international court. Greenpeace submits it to BuzzFeed, and within an hour it’s running on TV stations across the globe.

Simons and Teulings are certain the ITLOS panel will see the footage. Nobody’s immune to the impact of those images, they think. Not even these unimpeachable judges. It could play a crucial role. That night they toast Phil Ball.

The next morning, 1,700 miles away, Phil is at gulyat, walking in circles in a box, when he hears Frank’s voice.

Читать дальше