Gerbil crosses his legs, explores the inside of his mouth with his tongue, lifts an eyebrow in a way that says, Well, here we are then .

‘How are you guys doing?’ says Dima nervously.

Gerbil nods slowly. ‘Good, Dimitri, good. How are you?’

‘I’ve been better.’

‘Yeeees, I can imagine.’ The man leans forward, sniffs, meshes his fingers together to form a two-handed fist. ‘Listen, now the piracy charge has been dropped we thought it was time we started talking. You and us.’

‘Okay.’

‘It’s getting serious now, Dimitri. We’re in the end game. The hooligan charge is going to stick, you’re looking at seven years, you know that. So we’d really like to hear from you, this time without any protocol’ – he means Article 51 of the constitution, the right to silence – ‘and it would be really good if you gave us some answers. To the questions, I mean. You know, about what happened out there.’ He waves a hand in the air. ‘We know most of it anyway, but just to get it confirmed. It’s your only chance of skirting that rap.’

‘Okaaay.’ Dima draws a deep breath. ‘And who are you, exactly?’

The man clears his throat. ‘Well…’ He smiles. ‘We’re the competent authorities.’

‘The competent authorities?’

‘That’s right.’

‘And what is your field of competence, exactly?’

His bottom lip protrudes for a moment as he shrugs. ‘This.’

‘And… what is this ?’

‘Don’t you understand what I’m saying to you?’

‘I’m afraid I don’t.’

‘We’re the competent authorities.’

‘You already said that.’

‘Dimitri, please, come now, stop messing around, stop playing these…’ his face creases, he touches his nose ‘… these childish games. Let’s just get the questions answered, okay? Better for everyone.’

‘I’m perfectly willing to answer any questions from the investigators.’

‘Ah, good.’

‘With my lawyer present of course.’

‘Aaaaah, the lawyers.’

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘Come come, don’t you understand what these lawyers are after? They want to keep you in prison for as long as possible, you know that, Dimitri. Paid by the hour. Making a lot of money.’ Gerbil taps the edge of the table with a finger. ‘How much do you make, Dimitri? At Greenpeace?’

‘It’s not about the money.’

‘Sure.’ He nods with faux sincerity. ‘Sure it’s not.’

‘Really.’

‘Well I’ll tell you, they make a lot more money than you do, those lawyers you’ve hired. A lot more. They really don’t want to get you guys out, not while they’re raking it in. Nooooo. So look, let’s forget about the lawyers for a moment and let’s talk about you, about what’s in your interests. We can make your stay here much more comfortable, a lot more comfortable than it is now. And all you have to do is answer our questions.’ He looks away. ‘It’s just for background anyway.’

‘My stay in prison is perfectly comfortable already, thank you.’

‘Well, you know, it could be much worse. Think about that, Dimitri.’

Gerbil pushes the chair back and stands up. His colleague does the same.

‘That’s it?’ Dima asks.

‘For now.’

The other cop unlocks the door. Gerbil tugs Dima’s arm and leads him out. Putin looks down, silent, inscrutable.

Dima is lying on his bunk, smoking a cigarette, running over what happened back there. Is he being singled out for special treatment? Is he going down for years while everyone else gets released? Nobody else is getting this shit, or if they are then they’re not talking about it on the road. For hours Dima’s been reconstructing the conversation with the competent authorities, but he can’t work out what it means, and now he’s exhausted.

He sucks on the butt of his cigarette, crushes it against the inside of a tin can and lights up another.

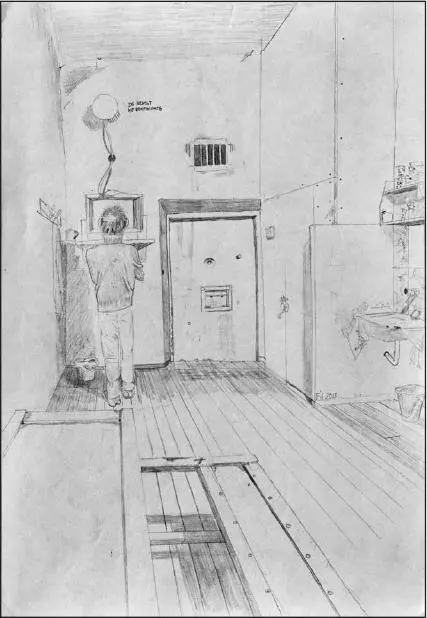

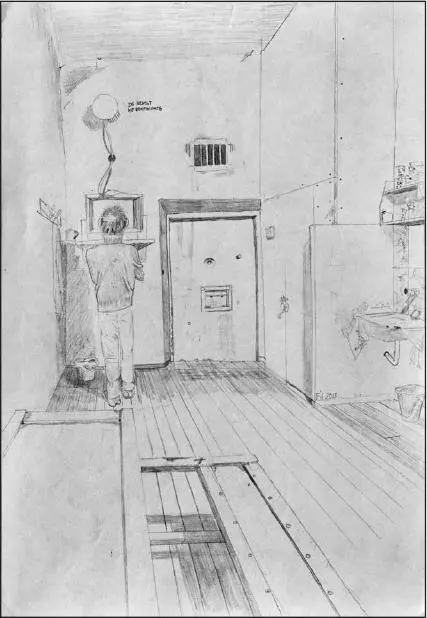

Dima Litvinov never thought he’d become a real smoker, but honestly, there’s no point not smoking in here. Vitaly and Alexei both smoke strong Russian cigarettes all day long and a thick fog hangs in the cell whenever somebody is awake. Sometimes Dima can barely see the opposite wall. Just by being in here he inhales as much smoke as he’d ever get from actually smoking himself. So sometime around the second week he decided he might as well get some pleasure from it. He took up cigarettes.

They come free on the doroga, all you do is send a note out and the kotlovaya will arrange for a packet to be sent your way. And once he started, he realised there was no point in giving up. He could have quit but he’d still suffer the same harm to his health, and without getting any of the pleasure. Cigarettes give a rhythm to the day. They break the boredom. The only way it would be worthwhile quitting smoking in this cell is if he could get the other two to quit as well, but there’s no chance of them giving up because the rest of the cell is always smoking.

Dima takes a drag and stares at the ceiling. It’s a classic paradox. It only takes one of them to light up to make it pointless for the others to give up, because they share the same air. Maybe I should just quit, he thinks. Then persuade the others to give up too. Maybe somebody just needs to jump first.

The women tap to each other in code. Frank has his Valium prescription. Dima smokes cigarettes or goes uyti v tryapki – ‘into the rags’. Each of the thirty finds a different way to survive. For Anthony Perrett, it’s the Gulag Chronicle .

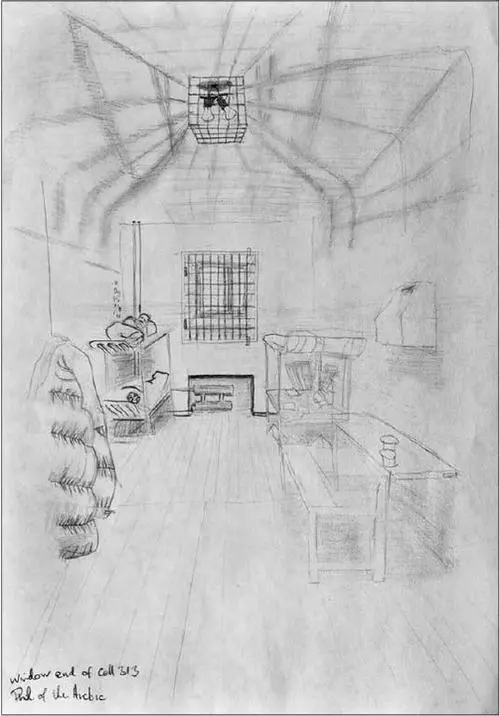

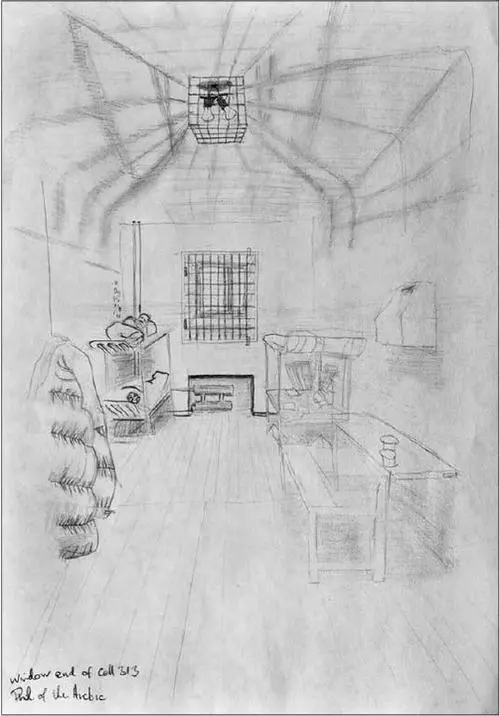

The idea came one night soon after they were jailed, when he was talking to Phil on the road. Both love to draw, from day one they immersed themselves in sketches of the cells, of the other prisoners, the guards, the raid on the ship. And it’s not like there was a shortage of news. So Phil suggested they start a newspaper. His plan was to circulate a daily with empty space where the other prisoners could write their own stories. Anthony was less interested in what the others had to say, instead he wanted to write, edit, illustrate, publish and circulate his own paper. Phil pushed ahead with his idea and for two days his publication – the Gulag Gazette – had a tabloid monopoly. But Anthony was merely biding his time, for he had an altogether different concept in publishing.

The Gulag Chronicle .

He launched with three editions on a single night, including an editorial that ripped into Phil and his dirty rag. ‘Do not read the Gazette, it’s nonsense, the editor’s a moron.’ Then he sent it all out on the road.

Soon enough the Gazette folded and demands flowed into Anthony’s cell to make the Chronicle into a daily. It became a prison fixture. His serving of satire and gossip was eagerly anticipated by the activists. The sixteenth edition was a particular hit with the readers. On the front page, in banner type, sat the headline: ‘SIT STILL AND SAVE THE WORLD’. And below that ran the day’s lead story.

It has been observed that we merry few locked in our cells are, willingly or not, completing many campaign objectives by sitting on our arses thinking of home. Despite our jailors, we are doing our jobs better the longer our incarceration continues. Allow a small prophecy if you will. This detention shows many nations that Greenpeace will not cower in the face of adversity, it will persevere where others fear to tread. This persistence will put negative press at the top of all oil companies’ board meeting agendas. These risk-averse project-monkeys will be forced to look at new energy sources, which will eventually lead to new economies and end the march into the northern wilderness for black gold!

Читать дальше