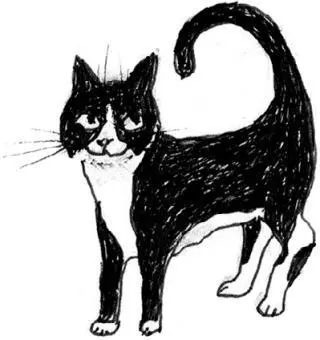

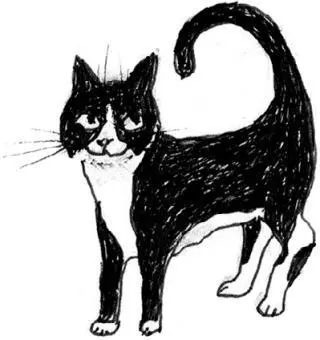

WE WERE READING Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Beginning of Spring aloud before dinner last night when Pard came trotting through the living room in an uncharacteristically feral way: body low to the ground, tail down, head poised, eyes all black pupil. And sure enough, a small mouse in his mouth. He put it down, let it go, recaught it, and trotted on back to the kitchen, the tiny black tail hanging out of his mouth. We went on grimly with Penelope. After a while Pard came back, mouseless, and looking clueless. He wandered off, and we decided, or hoped, he’d lost the mouse.

Just as we were about to do the dishes he reappeared with it. It was now distinctly less active, but still alive. Pard was confused, troubled, and purposeless, as he always is when he has caught a mouse: totally possessed by the instinctive command to hunt, to catch, to bring the catch to the family as trophy or toy or food, but lacking any instinct or instruction as to how to follow through to the kill.

A cat with a mouse—the cliché example of cruelty. I want to say clearly that I do not believe any animal is capable of being cruel. Cruelty implies consciousness of another’s pain and the intent to cause it. Cruelty is a human specialty, which human beings continue to practice, and perfect, and institutionalize, though we seldom boast about it. We prefer to disown it, calling it “inhumanity,” ascribing it to animals. We don’t want to admit the innocence of the animals, which reveals our guilt.

It’s possible that I could have caught the mouse and taken it outside to spare it some suffering. (Charles couldn’t, because after an operation a little while ago he’s forbidden to stoop down.) I didn’t even try. To do it, I’d have to be highly motivated, and I’m not. I feel neither guilty nor ashamed of that, only unhappy about the whole situation.

I’ve never been able to come between a cat and its prey. When I was twelve or so our tomcat caught a sparrow on the lawn. Two of my brothers and my father were there. All three shouted at the cat, tried to get the bird away from it, and succeeded, in a cloud of feathers and confusion. I recall clearly, because I was clearly aware of my own feelings at the time, my refusal to join the shouting and scolding and scrambling. I disapproved. I thought the matter was between the bird and the cat and we had no business interfering with it. This may appear very cold-blooded, and perhaps it is. There are certain other matters of life and death toward which I have a similarly instant, absolute, imperative response—it is right to do this, or it is wrong to do this—which is not affected by personal preference or tenderness, has nothing to do with the reasonings of conscience, and cannot be justified by the arguments of ordinary morality. But neither can it be shaken by them.

Our feeble solution to Pard and the mouse’s problem was to shut them into the kitchen, leaving them to work it out in their own way. (And the dishes to be done in the morning.) What the mouse needed was to find the hole he’d come in by. Pard’s box is in the kitchen porch and his water bowl on the kitchen floor, so Pard had all he needed. Plus his problem.

And minus us. He is a very human-dependent cat. He’s almost always unobtrusively nearby. Fits of flying about at eye level, wreaking sudden havoc on bedspreads, galloping madly up flights of stairs, and bouncing backward stiff-legged and humpbacked with enormous tail and glaring eyes down the hall ahead of you for no reason occur now and then, but mostly he’s just quietly somewhere near one or the other of us. Keeping an eye on us, or sleeping. (Right now he’s conked out on his beloved Moebius scarf right next to the Time Machine, about eighteen inches from my right elbow.) Nights he almost always spends on my bed around the vicinity of my knees.

So I knew I’d miss him last night and he’d miss me. And we did. I got up to pee at around 2 a.m. and could just hear him weeping softly down in the kitchen. All the way home from the Humane Society in the carrier, he meowed and yowled lustily, but since then he’s never raised his voice. Even when shut by mistake in the basement, he just stands at the door and cries, softly, Meew? till somebody happens to hear him.

I steeled my heart, went back to bed, and felt bad till 3:30.

In the morning getting dressed I heard Meew? again, so I dressed fast, hurried down, and opened the kitchen door. There was Pard, still puzzled, still anxious, but tail in the air to greet me and breakfast.

There was no mouse.

These chapters of the saga almost always end now in mystery. An unhappy mystery.

A result, maybe, of the only partly worked-out relationship between two immensely different ways of being, the human and the feline. Wild cat and wild mouse have a clear, highly developed, well-understood connection—predator and prey. But Pard’s and his ancestors’ relationship with human beings has interfered with his instincts, confusing that fierce clarity, half taming it, leaving him and his prey in an unsatisfactory, unhappy place.

People and dogs have been shaping each other’s character and behavior for thirty thousand years. People and cats have been working at transforming each other for only a tenth that long. We’re still in the early stages. Maybe that’s why it’s so interesting.

Oh, but I forgot the weird part! After I’d hurried downstairs this morning, as I got to the kitchen door, I saw a triangle of white on the floor under it, a piece of paper. A message had been shoved under the door.

I stood and stared at it.

Was it going to say “Please let me out” in Cat?

I picked it up and saw a friend’s telephone number scribbled in pencil. The scrap of paper had fallen off the telephone table in the kitchen hall. Pard was still saying Meew? very politely behind the door. So I opened it. And we had our reunion.

His paws are white, his ears are black.

When he isn’t around I feel the lack.

His purr is loud, his fur is soft.

He always carries his tail aloft.

His gait is easy, his gaze intense.

He wears a tuxedo to all events.

His toes are prickly, his nose is pink.

I like to watch him sit and think.

His breed is Alley, his name is Pard.

Life without him would be hard.

Part Four

REWARDS

The Circling Stars, the Sea Surrounding: Philip Glass and John Luther Adams

April 2014

EVERY YEAR ONE of the Portland Opera Company’s productions is sung by the singers in the company’s outstanding training program. In 2012 it was Philip Glass’s short opera Galileo Galilei . There is a splendor to young voices different from the patina of the experienced singer; and these performances always have an extra charge of tension and excitement.

The bold, beautiful, intricately simple set, all circles and arcs and moving lights on different planes, was, I believe, from the Chicago premiere in 2002; the conductor was Anne Manson.

The first scene shows us Galileo old, blind, and alone. From there the story follows a reverse spiral through time, revolving back lightly and ceaselessly through his trial, his triumphs, his discoveries, to the last scene, where a little boy named Galileo sits hearing an opera about Orion and the Dawn and the circling planets written by his father, Vincenzo Galilei. It is all borne along and buoyed up by the endlessly repetitive and ever-changing music, always spiraling, never resting, and yet moving with the slow majesty of the great orbits, without reference to any beginning or ending, in a vast, joyous continuity. It moves, it moves, it moves… E pur si muove!

Читать дальше