Soldiers and officers also have ideas about what is acceptable in warfare, and these ideas have an important impact on technological development. In previous centuries, armies faced each other in set-piece confrontations, in ways that, by present-day standards, seem incredibly restrained. Then, relatively few civilians were killed; technologies were designed mainly for killing soldiers. Today, many more civilians are killed in wars than soldiers; weapons of mass destruction are designed for this purpose.

Most people are highly reluctant to hurt others. Soldiers have to be trained to kill, especially when the enemy is confronted face-to-face. There is evidence that most front-line soldiers in World War II and other wars did not fire their rifles, and that many of those who did fire intended to miss. In many countries, armies cannot be filled by volunteers; conscription is needed. Technological development has made it easier to kill at a distance, without recognising the enemy as a person. Engineers who design bombers and pilots who fly them can maintain a psychological distance from the people who are being attacked. It is possible to see much of modern weapons development as a response to a pressure to use fewer people in fighting and to reduce the need for face-to-face combat. In this way, the repulsion most people feel towards killing is sidestepped. Another way to overcome this repulsion is to train soldiers using highly realistic simulations so that responses become automatic. This has been done increasingly in the US military since World War II, with correspondingly greater psychological impacts on those soldiers who engage in “intimate” killing, such as in the Vietnam war. [35] . Dave Grossman, On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (Boston: Little, Brown, 1995).

With modern poisons and other small weapons, it is now possible for one individual behind enemy lines — especially an agent who has joined the other side’s armed forces — to be more potent than a whole battalion of front-line soldiers. By planting poisons in water supplies or in the food of individuals or by just slitting throats, one agent could kill hundreds of soldiers and cause a crisis in morale. Technological developments could aid such an approach to warfare. But this has not been a major R&D focus compared to conventional weapons. One reason is that it would be difficult to recruit soldiers to undertake this sort of killing. Also, if adopted by both sides, it would be a threat to the military command, since agents would target officers who, in conventional warfare, are least likely to be killed.

* * *

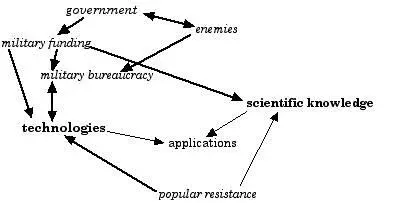

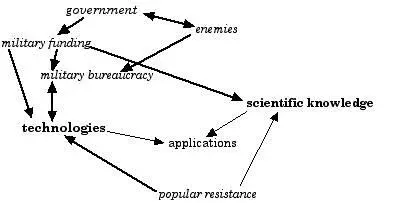

Taking into account these various countervailing influences, it is possible to present a more complicated picture of military shaping of science and technology. Figure 3 shows some of the influences and some of the connections.

Figure 3. A model of military shaping showing a variety of specific influences on science and technology.

So far in this discussion of military influences on the development and use of technologies, it has been assumed that the purpose of the military is simply to defend societies against aggression. This is the usual picture drawn by militaries and governments and widely believed by members of the public. But there is another viewpoint: that the military is tied in fundamental ways to social structures, especially the state, capitalism, bureaucracy and patriarchy. In this picture, the military both supports and is supported by these structures. This has implications for understanding military-related technology.

Only occasionally are contemporary military forces used to engage in combat against military forces of another country. It is actually much more common for a country’s military to be used against the people of the country itself, most obviously in military dictatorships. This suggests that militaries have as much to do with social control — in the interests of certain groups in a society — as with defence against foreign threats. At the global level, military forces and alliances such as NATO serve to protect dominant groups from challenge. For example, NATO troops help to sustain global economic inequality.

The state, in a sociological sense, can be defined as a community based on a monopoly over organised violence within a territory, this violence being considered “legitimate” by the state itself. [36] . There is a large amount of writing about various forces that have weakened the power of the state, including transnational corporations, international organisations and social movements. Undoubtedly the state is no longer hegemonic, if it ever was. When it comes to examining the military, the state remains the dominant influence, but there is an increasing role being played by mercenaries, militias and international “peacekeeping” forces. Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999) provides an insightful analysis of the recent transformation of war from state-based invasion-and-defence mode to a postmodern form with state, paramilitary, criminal and international actors involved in a mixture of war, organised crime and mass human rights violations.

In modern societies, organised violence is only considered legitimate when exercised by the police or the military. The state is more commonly thought of as being composed of the government (including national and local officials), government bureaucracies, the legal system, the military, and government-run operations such as schools. The state maintains itself financially mainly through taxes, administers services and regulations through government bureaucracies, and maintains order through the police and the legal system. In any major challenge to the system — such as refusal to pay taxes — the police and, if necessary, the military are available to maintain state power. War is a primary impetus behind the rise of the state. Indeed, war-making and state-making are mutually reinforcing. [37] . On the state and the military, see Ekkehart Krippendorff, Staat und Krieg: Die Historische Logik Politischer Unvernunft (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1985), as reviewed by Johan Galtung, “The state, the military and war,” Journal of Peace Research , Vol. 26, No. 1, 1989, pp. 101-105 (I thank Mary Cawte for this reference); Bruce D. Porter, War and the Rise of the State: The Military Foundations of Modern Politics (New York: Free Press, 1994); Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990-1992 (Cambridge MA: Blackwell, 1992). For the case of the US, see Gregory Hooks, Forging the Military-Industrial Complex: World War II’s Battle of the Potomac (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991).

The state must defend against external threats, to be sure, but internal threats are more frequent and more complex. Most contemporary states administer unequal societies, with wealth, status and privilege distributed very unevenly, usually accompanied by systematic methods to maintain this inequality, such as class structure and sexual and ethnic discrimination. The pervasive injustice of societies stimulates challenges to the status quo. In societies with representative governments, the usual methods of social control are schooling, manipulation of perception through the mass media, systems of legitimacy such as parliaments and courts, and the economic system. But when these systems are not sufficient to protect the interests of dominant groups, the police and the military may be deployed, for example to arrest demonstrators or break strikes.

During the cold war, the superpowers could justify their massive arsenals by pointing to the threat posed by the enemy. The cold war is over but military spending, though somewhat cut back, continues at a very high rate. It has been widely remarked by commentators that the US Department of Defense and spy agencies have been desperately searching for new legitimations for their existence — favourite rationales are “rogue states,” terrorism and the drug trade. The lack of an overt justification for a continuing military megamachine provides added weight to explanations referring to the military’s role in maintaining systems of inequality.

Читать дальше