Over the past decades, and particularly since the Second Vatican Council, the Roman Catholic Church has been faced with nearly every sort of cultural, doctrinal and political dissent. In Latin America, where it faces an unprecedented challenge from evangelical Protestantism and from the populist challenge of so-called ‘liberation theology’, the need to renew the priesthood has led to questioning of the celibacy requirement. In the United States and Western Europe, the congregation appears to conduct its affairs without reference to canonical teaching on birth control. Homosexual groups have petitioned for the right to be considered true Catholics, since if God did not create their condition there seems to be an interesting question as to who did. Even prominent. Catholic writers of the conservative wing, such as William Buckley and Clare Booth Luce, have made the obvious point that an unyielding opposition to contraception, and the ranking of it as a sin more or less equivalent to abortion, is, among other things, a cheapening of the moral position on abortion itself.

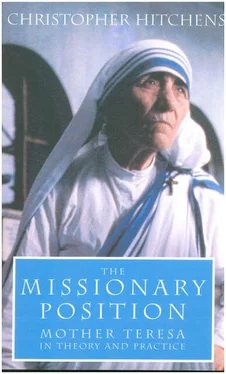

In all of these debates, the most consistently reactionary figure has been Mother Teresa. The fundamentalist faction within the Vatican has found her useful in two ways — first as an advertisement for the good works of the Church to non-Catholics; and second as a potent instrument of moral suasion within the ranks of the existing faithful. She has missed no opportunity to restate elementary dogmas (much as she once told an interviewer that, if faced with a choice between Galileo and the authority of the Inquisition, she would have sided with the Church authorities). She has inveighed against abortion, against contraception and against the idea that there should be any limit whatsoever to the growth of world population. [4] In the course of preparing for the 1994 United Nations World Population Conference in Cairo, the Vatican went so far as to make a temporary alliance with those forces of Shi’a Islam, chiefly represented by the mullahs of Iran, which denounced population control as an imperialist conspiracy. The apple of dogma had, at least in this case, fallen some distance from the tree of proselytization and the crusades.

When Mother Teresa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979, few people had the poor taste to ask what she had ever done, or even claimed to do, for the cause of peace. Her address to the ceremony of investiture did little to resolve any doubt on this score and much to increase it. She began the speech with a literal-minded account of the myth of Christ’s conception, perhaps in honour of that day’s festal character: the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. Then she began her diatribe:

I was amazed when I learned that in the West so many young people are on drugs. I tried to understand the reason for this. Why? The answer is, ‘because in the family there is nobody who cares about them’. Fathers and mothers are so busy they have no time. Young parents work, and the child lives in the street and goes his own way. We speak of peace. These are the things that threaten peace. I think that today peace is threatened by abortion, too, which is a true war, the direct killing of a child by its own mother. In the Bible we read that God clearly said: ‘Even though a mother did forget her infant, I will not forget him.’

Today, abortion is the worst evil, and the greatest enemy of peace. We who are here today were wanted by our parents. We would not be here if our parents had not wanted us.

We want children, and we love them. But what about the other millions? Many are concerned about the children, like those in Africa, who die in great numbers either from hunger or for other reasons. But millions of children die intentionally, by the will of their mothers. Because if a mother can kill her own child, what will prevent us from killing ourselves, or one another? Nothing.

There is not much necessity for identifying the fallacies and distortions which are piled upon one another here. Few women who have had abortions, even those who still feel remorse or regret, will recognize themselves as having committed actual infanticide. If there are ‘millions’ of children being slain in this way, so that they compare to the millions of children dying of malnutrition and pestilence, then there is clearly no hope for Mother Teresa’s adoption solution. (She claims to have rescued only three or four dozen orphans from the entire Bangladesh calamity, for example.) Moreover, these impressive figures should be enough at least to impel reconsideration in those who proclaim that all pregnancies are ‘wanted’ by definition and that there can be no excess population.

At a vast open-air mass in Knock, Ireland, in 1992, Mother Teresa made, it plain yet again that there is no connection at all in her mind between the conditions of poverty and misery that she ‘combats’ and the inability of the very poor to reach the plateau on which limitation of family size becomes a rational choice. Addressing a crowd of the devout, she said, ‘Let us promise Our Lady who loves Ireland so much that we will never allow in this country a single abortion. And no contraceptives.’

In this instance, she fell into the last great fallacy and offence to which Church teaching on this subject is prone. Ireland is now, to a great extent, a secular society. It is also a society which has to seek an accommodation with its huge Protestant-majority province. The Church claims the right to make law, in states where it is strong enough, for believers and unbelievers alike. Mother Teresa’s ‘pacific’ humanitarianism and charity therefore translate directly into an injunction to the faithful to breed without hindrance, an admonishment to the rest to live under laws not made by them, and an attack on the idea of a nonsectarian state. What this does for the cause of peace does not, in Ireland, take long to estimate. What it does for suffering humanity is to criminalize, or at least to ration and restrict, one of the few means ever devised for its self-emancipation. It is often said, inside the Church and out of it, that there is something grotesque about lectures on the sexual life when delivered by those who have shunned it. Given the way that the Church forbids women to preach, this point is usually made about men. But given how much this Church allows the fanatical Mother Teresa to preach, it might be added that the call to go forth and multiply, and to take no thought for the morrow, sounds grotesque when uttered by an elderly virgin whose chief claim to reverence is that she ministers to the inevitable losers in this very lottery.

In her reputation-making interview with Malcolm Muggeridge during Something Beautiful for God, Mother Teresa made the following large claim:

We have to do God’s will in everything. We also take a special vow which other congregations don’t take; that of giving wholehearted free service to the poor. This vow means that we cannot work for the rich; neither can we accept any money for the work we do. Ours has to be a free service, and to the poor.

For the many ethical humanists, as well as for the many vaguely religious people who support or endorse what they imagine to be Mother Teresa’s mission, the above statement is quite an important one. It seems to spare the Missionaries of Charity from the worldliness and financial cunning which have so disfigured Christianity in the past. And it insists that no service is furnished to the rich — a claim which might lead the unwary to conclude that no contributions are solicited from them.

In point of fact, the Missionaries of Charity have for decades been the recipients of the extraordinary largesse of governments, large foundations, corporations and private citizens. The affectation of poverty, which is so attractive to some observers, has obscured this relative plenty. And so has another affectation — one very well known to missionary fund-raisers down through the years. In this story, which has become solemnized by repetition at a thousand tent meetings, the necessary donation arrives justatthe moment when the need for it is greatest. Was a consignment of blankets the pressing need, with a hard winter coming on? Sure enough, an anonymous benefactor chose that very night to leave a truckload of blankets on the doorstep of the mission. Dr Lush Gjergji gives an especially touching example of the genre in his book, an example no less touching for its being written as if the notion had never been tried out in print before:

Читать дальше