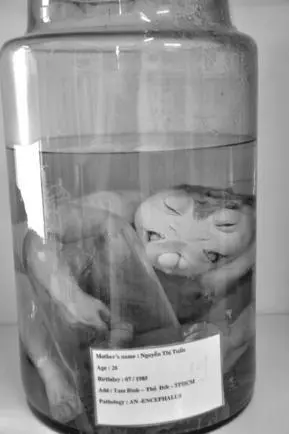

Dr. Phuong delivered more and more babies with missing limbs, two bodies fused together with one set of internal organs; babies with partial or missing brains, missing heads, babies that didn’t open their eyes, didn’t cry, and died within a few days after delivery. Instead of fully formed fetuses, some women at Tu Du gave birth to formless bloody lumps. In late 1967, following a period of massive use of Agent Orange in Vietnam, Saigon newspapers began publishing reports on a new birth abnormality, calling it the “egg bundle-like fetus.” Photographs of this “egg bundle” appeared on the front page of some South Vietnam newspapers. One paper, Dong Nai published an article about women giving birth to stillborn fetuses, with a photograph of a dead baby whose face was that of a duck. A day later, Dong Nai ran a story about a woman giving birth to a baby with “two heads, three arms, and twenty fingers.” Just above the article, the paper posted a photograph of another deformed baby with a head that resembled that of a poodle or a sheep. Still another Saigon newspaper, Tia Sang , on June 26, 1969, printed a picture of a baby with “three legs, a head squeezed in close to the legs, and two arms wrapped around a big bag that replaced the lower section of the face…” 1

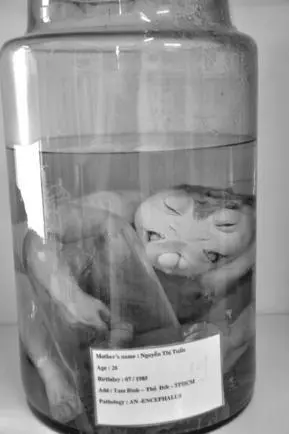

Anencephalus (baby born with a substantial part of its brain missing).

The Saigon government’s counterargument was that these birth defects were caused by something it called “Okinawa bacteria.” 2

Hydrocephalus (babies born with water on the brain).

I’ve read about Dr. Phuong’s work for many years, and consider it an honor that she has taken the time to talk about what must be, even after all these years, a painful subject. For some people, this would be an opportunity to launch into a monologue about being misunderstood, marginalized, and ridiculed. But the Vietnamese with whom we meet rarely talk about themselves, and they never complain. When they do speak of their efforts to convince skeptics that the Vietnamese have suffered catastrophic injuries as a result of chemical warfare, it is without the slightest hint of self-aggrandizement or self-pity.

Dr. Phuong wanted people to know about the increasing number of deformed babies she and other staff were seeing in Tu Du Hospital’s delivery room.

“So I contacted a newspaper,” she smiles. “One that was not part of the regime at the time, but people didn’t really believe me. Not in the South, anyway. Only in Hanoi did I have any real support. People there were far less skeptical about what the spraying was doing to people in Vietnam.”

Dr. Phuong could not have known that soon after the United States military commenced full-scale use of Agent Orange in Vietnam, Dow Chemical, one of the principal manufacturers of this herbicide, invited representatives from other companies to attend an urgent meeting. Once there, Dow revealed that Agent Orange contained TCDD-dioxin, the most toxic chemical company researchers had ever encountered.

Dow’s scientists believed that TCDD-dioxin was one hundred times as toxic as Parathion, a chemical that Rachel Carson described in Silent Spring as an organic phosphate, “one of the most powerful and dangerous.” 3

Dow called a meeting and advised those present—Hooker Chemical, Hercules, and Diamond Alkali—not to reveal what they might know about the harmful effects of dioxin. If the government found out about the potential dangers of this chemical, it might impose regulations on the production of herbicides.

While Dr. Phuong struggled with how to console young mothers who’d given birth to hopelessly deformed babies, scientists in the US discovered that even in the lowest doses given, 2,4,5-T, one of the herbicides in Agent Orange, caused cleft palates, missing and deformed eyes, cystic kidneys, and enlarged livers in the offspring of laboratory animals. The results of this study would be withheld until 1969, the year Dr. Phuong spared a young mother from knowing that she had given birth to a monster.

In 1971, Thomas Whiteside published The Withering Rain , an early look at the use of herbicides in Vietnam. A careful, scrupulous researcher, Whiteside set out to speak with officials at Dow Chemical and government scientists he assumed would be forthcoming about the effects of herbicides on human beings and the environment.

“I was hardly surprised,” writes Whiteside,

to find officials of the Dow Chemical Company, one of the largest manufacturers of 2,4,5-T, uncommunicative. But I was taken aback to encounter plain antagonism from several scientists connected with the government when I raised with them what I thought were reasonable questions about the way in which information on the studies of the teratogenic, or fetus deforming, activity of 2,4,5-T in experimental animals had been handled. They intimated that such matters were beyond the understanding of laymen and comprehensible only to professional biologists.

“I found this kind of attitude disappointing,” continued Whiteside in characteristic understatement,

in people who I had supposed were devoted to the search for scientific truth. I formed the suspicion that this professional grandiosity was in part something very like a cover for timidity—a reluctance to discuss even a prima facie case against potentially dangerous compounds for fear of a whipping by professional critics at the next scientific convention.

Dismayed by the cavalier attitude of an official at the laboratory where scientists discovered that “2,4,5-T exerted clearly teratogenic effects on experimental mice and rats,” Whiteside notes, “what we were talking about was a spray rate of 2,4,5-T that, at least as laid down in Vietnam, could result in a pregnant Vietnamese woman’s ingesting close to an equivalent amount of 2,4,5-T that, in experimental rats, deformed one out of three of the rats’ unborn offspring.” 4

Dr. Phuong sketches a picture of a “mole baby,” a large egg shape, open at one end, containing “bloody liquid.” Inside of the egg shape she draws many small circles, labeling them “frogs legs.” Beside her drawing, she writes: hydatidiform mole, chorio carcinoma .

“I was very much criticized by my colleagues,” says Dr. Phuong. “I saw the babies, and I knew that sooner or later people would begin to believe me, but it took ten years until they did. I just felt the need to find out what was wrong, and I wanted to do something to help the parents and the children.

“It was really only after 1975 that we began to know more about the consequences of Agent Orange. It was hard at that time to find a lot of documentation about the effects of herbicides on the environment and people. Bert Pfeiffer and Arthur Westing from the National Academy of Science had conducted research in Vietnam and Cambodia, but most of their work centered on the effects of herbicides on plant life, rather than human beings. In March 2006, at the International Conference of Victims of Agent Orange held in Hanoi, Vietnam, former Marine Daniel J. Shea talked about his son, Casey, who was born with congenital heart disease, a cleft palate, and stomach abnormalities. When Casey was three years old, doctors told the family that he needed a shunt in his heart to help the flow of oxygen, but the child went into a coma during surgery and later died in his father’s arms.

“What right,” a tearful Daniel Shea asked the audience, “does anyone have to make chemical potions to poison the land and its people?… Is it not criminal, even in times of war, to poison a people’s food crops? The world has condemned chemical warfare because it takes not only enemy soldiers, but innocent men, women, and children alike… and it cripples generation after generation of those exposed to its toxins.” 5

Читать дальше