The Hague Convention IV and the 1925 Geneva Protocol were designed to prevent nation-states from using biological and chemical weapons against their adversaries in warfare. Unfortunately, those responsible for the manufacture of Agent Orange and the use of this herbicide in Vietnam treat these treaties like linguistic pawns in a game of high-stakes legal and financial chess. I wonder what the stockholders in highly profitable corporations like Dow and Monsanto feel about this game.

It appears that the chemical companies have outsmarted Vietnam veterans, the Vietnamese, hard-working, dedicated, brilliant lawyers, and powerful law firms. They played by the rules, and they won. But think again. Better yet, spend an afternoon watching lawyers who work for these companies knock about in the Realm. It won’t take you long to discover that they appear to cast spells over the courtroom, forcing learned judges to follow the bouncing Orwellian ball. You might laugh, but not too loud or the marshals will toss you out. You might cry, but make sure you don’t do anything to interfere with the magic show.

On the way home, you might stop for a drink with friends. You will try to tell them about the Realm. They will ask a lot of questions, and you will do your best to be clear and precise and honest. The Realm, you will say, is a very strange, exotic, confusing, contradictory place. Impossible to believe, even when you see it.

CHAPTER 10

Free Fire Zone

It will take a long time to clarify the exact consequences of Agent Orange.

—Douglas Peterson, US Ambassador to Vietnam

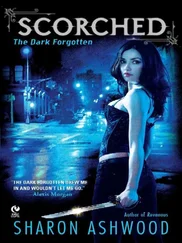

Blind soldier

Cu Chi district, a short drive from our hotel in downtown Ho Chi Minh City, was the scene of fierce fighting during the war. It was here that men from the 25th Infantry stumbled upon a labyrinth of tunnels stretching all the way from the outskirts of Saigon to the Cambodian border. Two hundred miles of tunnels (soldiers dubbed them the “IRT,” after one of New York City’s subway lines) dug by men and women using small shovels and even spoons. Inside of these tunnels, the people General William Westmoreland called “human moles” constructed sleeping quarters, storage facilities, hospitals, and factories for building facsimiles of American weapons. Year after year, “tunnel rats” crawled into dark, fetid, dangerous holes, trying to find and kill these “moles.” The military pumped CS gas into Cu Chi’s tunnels, planted explosives inside of them, and tried to flood them, hoping to destroy the enemy’s ability to pop out of the ground, to wound and kill unsuspecting Americans, and then to vanish without a trace. 1

In the late 1950s, Ngo Dinh Diem, the anticommunist aristocrat the Eisenhower administration had installed as “President” of “South Vietnam,” launched a reign of terror in Cu Chi district, arresting, torturing, jailing, and killing perceived opponents of his tyrannical regime, including thousands of Vietminh who’d fought against the French colonialists. In December 1958, Diem’s jailers fed poisoned bread to several hundred prisoners at a camp in Phu Loi, just a few miles from Cu Chi. At the village of Phuoc Hiep, north of Cu Chi town, Diem’s troops fired into crowds of peaceful marchers. Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, rounded up suspected communists and guillotined them in the public squares of small villages. 2

Returning from a visit to Vietnam in May 1961, Vice-President Lyndon Johnson called Diem the “Winston Churchill of the decade… in the vanguard of those leaders who stand for freedom.” South Vietnam, said President John F. Kennedy, was a “proving ground for democracy.” 3

In 1961, Ngo Dinh Nhu supervised the opening of the first “strategic hamlet” camps (the Vietnamese called these places concentration camps) in Cu Chi district. The strategy was to separate Vietnamese civilians from communist insurgents. The South Vietnamese Army and later the US military destroyed entire communities, killing farm animals, ruining crops, and herding peasants into crowded camps that lacked food, water, and sanitation facilities. Peasants in Cu Chi district simply walked out of these “hamlets” and went back to whatever might be left of their homes.

On November 2, 1963, Ngo Din Diem and his brother were murdered in a coup supported by the American ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. In August 1964, Congress passed the “Gulf of Tonkin Resolution,” giving President Johnson powers to expand the war in Vietnam.

Forty years later, the mangrove forests and jungles that once covered the Cu Chi district are gone, leaving a landscape that resembles the fields of Iowa rather than the wilds of Southeast Asia. We pass small houses, with brown hump-neck cows standing by the front door, as though waiting to be invited inside for a glass of green tea. Rice fields, water buffalo, chickens, ducks, tiny stores and cafés tucked into flowering shrubbery, children playing beside the roads: little evidence that Cu Chi district was bombed, burned, gassed, defoliated, and bulldozed every single day for a decade.

The old soldier wears a long-sleeved shirt and shorts. His feet are bare and when he talks he appears to be listening carefully to his own words. Once, he says, this area of Cu Chi was covered with mangrove forests and jungles. Then, the spray planes appeared, moving slowly and quite low over the trees, back and forth until everything shriveled up and died.

I watch the man’s face, trying to guess what he must be thinking or feeling. Does the sound of my voice trigger visions of ambushes, firefights, and death? He pulls at his right sleeve, touches his chest, and explains that two bullets are lodged in his body, one in his right arm, and the other a few inches from his heart. After fighting for fifteen years in the forests and rice paddies, swamps and tunnels, he was blinded during a battle at Saigon’s Ton Son Hut airport. His wife serves glasses of green tea and returns to the next room to attend to their son.

Le Van Can fought first in the Cu Chi region, but moved on to other places after the forests were defoliated. In 1969, he says, the United States sprayed Agent Orange everywhere. Day after day, the planes appeared, showering the land with dioxin. He and the men in his unit tried to use their raincoats to protect them from defoliants, but the chemicals ate holes in their coats. Le Van Can’s unit moved from place to place, but it was impossible to escape the spraying; there wasn’t anywhere to hide.

He recalls that his skin got red and that it was difficult to sleep, but no one died or—so far as he knew at the time—got seriously ill from the spraying. It was only after the war that soldiers began to develop health problems. One man he knew came from Quang Tri, and when he returned home he fathered six children. Five of these children died. Many men he’d served with got sick and died after the war. He does not really know what caused their deaths, but he does recall a soldier who fathered one child, a daughter, who was born with a “big head.” She did not live very long.

Le Van Can doesn’t know whether his wife was exposed to Agent Orange, but since the US destroyed the forests in Cu Chi, she most likely ate food and drank water contaminated with dioxin.

Like all of the former soldiers we meet, our host speaks softly, without the slightest hint of bravado or, most peculiar to our American sensibilities, the tremble of anger in his voice. Perhaps, if I persisted, he might say something about the battles in which he fought, or the final push on April 30, 1975, into Saigon, ending forty years of war against the French colonialists and American armies.

Читать дальше