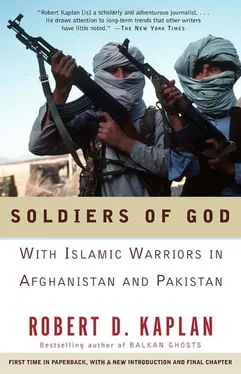

There were major battles in Afghanistan, but the only way to get to them on short notice was to fly, which was impossible, since the only people with planes were the Communists. Instead, for nearly a decade, the public was shown the same monotonous film clips of smoke billowing in the distance and of bearded, turbaned guerrillas with old rifles sniping at convoys — images that only increased the war’s unreality.

Afghanistan was too physically rough an assignment and offered too few rewards to draw the world’s best television cameramen. And it is the cameramen — not the high-profile correspondents — who hold the key to a television story’s impact. Had the very best cameramen traveled to the front lines, however, they would have been frustrated by the visual material they had to work with. The mujahidin were exotic all right, with their wide turbans, Lee-Enfield rifles, and great black beards. But the effect was static, flat. In Afghanistan, there was absolutely no clash between the strange and the familiar, which gave Vietnam and Lebanon their rock-video quality, with zonked-out GIs in headbands and rifle-wielding Shiite terrorists wearing Michael Jackson T-shirts.

Afghanistan existed without bridges to the twentieth century. The country was mired in medievalism; a “mass of mountains and peaks and glaciers,” as Kipling noted; a place where terrible things always happened to people. The Soviets destroyed it — but didn’t the Mongols too! In the January 20, 1980, issue of the Village Voice, the left-wing writer Alexander Cockburn employed such a rationale to justify the Soviet invasion of the month before:

We all have to go one day, but pray God let it not be over Afghanistan. An unspeakable country filled with unspeakable people, sheepshaggers and smugglers… I yield to none in my sympathy to those prostrate beneath the Russian jackboot, but if ever a country deserved rape it’s Afghanistan.

Cockburn’s tone was, of course, politically motivated. But given the West’s tepid public response to the subsequent Soviet occupation, it appeared that many people, deep down inside, reacted to Afghanistan in similar terms.

The images coming out of Afghanistan were simply beyond the grasp of the Western television audience. The Soviets had taken American tactics in Vietnam several steps further and fought a twenty-first-century war, a war that was completely impersonal and therefore too dangerous for journalists to cover properly, in which the only strategy was repeated aerial carpet bombings, terrorism, and the laying of millions of mines. The Hind helicopter gunship, the workhorse of the Soviet military in Afghanistan, packed no less than 128 rockets and four missiles. It was able to incinerate an entire village in a few seconds. Against such measures, the very concept of battle had become nearly obsolete.

While the Soviets waged a twenty-first-century war, the Afghans fought a nineteenth-century one. The Afghans were able to survive and drive out the Soviets precisely, and only, because they were so primitive. High birth and infant mortality rates in an unforgiving mountain environment, where disease was rife and medical care absent, had seemed to accelerate the process of evolution in rural Afghanistan, making the inhabitants of the countryside — where most of the mujahidin came from — arguably the physically toughest people on earth. They could go long periods of time without food and water, and climb up and down mountains like goats. Keeping up with them on their treks and surviving on what they survived on reduced me and other Westerners to tears. They seemed an extension of an impossible landscape that had ground up one foreign invader after another.

The mujahidin borrowed little from other modern guerrilla struggles. They had a small number of vehicles and, until the later stages of the war, few walkie-talkies, leaving the enemy without communications to intercept. Like the ancient Greeks, the mujahidin used runners to carry messages between outposts. Some areas of the country were blessed with exceptionally talented guerrilla commanders. But for the most part, the resistance fighters had no strategy to speak of, and their command structure was often so informal as to be nonexistent. A KhAD or KGB agent in their midst would have been hopelessly confused: there was nothing to infiltrate, and no pattern — often no logic or planning — to guerrilla attacks. Predicting the mujahidin’s actions was like forecasting the wind direction. In Peshawar, it was said that their very incompetence helped to defeat the Soviets (though after the Soviets departed, the complete disorganization of the resistance hindered its efforts to capture major Afghan cities still held by the Afghan Communists).

The mujahidin were a movement without rhetoric or ideology or a supreme leader — they had no Arafat or Savimbi or Mao. Their Moslem fundamentalism lacked political meaning because Afghanistan, unlike the Arab world and Iran, never had an invasion of Western culture and technology to revolt against. The guerrillas had no complexes, no chips on their shoulders regarding the modern world, since they had never clashed with it until the Soviets came. Religion for them was inseparable from the other certainties of a harsh and lonely mountain existence. In sum, the mujahidin had no politics; therefore, with few exceptions, they could not be extremists. Concepts like “the Third World” and “national liberation” had absolutely no meaning for them. After a trip to Paktia province in November 1987, William McGurn wrote in the European edition of the Wall Street Journal that the Afghan guerrillas were “simply ornery mountain folk who have not cottoned to a foreign power that has seized their land, killed their people and attacked their faith.”

If the mujahidin resembled anyone, it was the early-nineteenth-century Greek klephts, who with foreign help liberated their country from Ottoman Turkish occupation. Like the Afghans, the Greeks then were an unruly hodgepodge of guerrilla bands driven by a fervid religious faith (in their case, Orthodox Christianity). They were at a stage of development similar to that of Afghan peasants today: they lived an austere life in the mountains, were riven by blood feuds, and never forgot an insult. Lord Byron and the other foreign eccentrics who flocked to Greece in the 1820s to assist the rebels might have felt at home among the relief workers and journalists in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

The Afghans were able to withstand a late-twentieth-century military onslaught by relying on nineteenth-century values and methods. In The Face of Battle, John Keegan observed: “Impersonality, coercion, deliberate cruelty, all deployed on a rising scale, makes the fitness of modern man to sustain the stress of battle increasingly doubtful.” There is an awful lesson here: even conventional warfare is now so horrible that only the values of the past may make victory possible. And in Afghanistan, the lack of all-weather roads and a national press left the Afghans only the values of the past to fall back on, inward-oriented village codes that were undiluted by the rationalism that pervades not just the West but the more technologically developed parts of the Third World.

The Soviets killed a larger percentage of Afghans than the Nazis killed Soviets in World War II. Were Americans or Europeans to suffer the same level of mass violence today, it is questionable whether they would fight back as the Afghans have. More likely, they would seek some sort of compromise with their occupier.

The Afghan mujahidin, numbering over 100,000, were the first group of insurgents to drive out a Russian army since Czar Peter the Great began his empire’s southward expansion three hundred years ago. The mujahidin were attacked with more firepower than any Moslem group in the Middle East could imagine, yet almost never did they resort to terrorism. Though the guerrillas were responsible for political assassinations, the brutal treatment of enemy soldiers, and rocket attacks in Kabul and other cities that killed civilians, to my knowledge or that of any journalist I know, groups of Soviet or Afghan civilians were never deliberately singled out as targets. Because the mujahidin were innocent of the modern trait of terrorism, they did not inspire the horror and fascination of the car bombers and airplane hijackers, with their black hoods and nihilistic beliefs. The mujahidin, despite their many accomplishments, were not traditionally good subject matter for the media: they were neither complicated nor fanatical. They were the most understated of resistance fighters, and so, after a decade of war, they still had no face.

Читать дальше