Everyone rummages in their pockets. I offer a rouble but Kalinin puts out his hand to stop me.

“Today you’re our guest!”

One of my new friends runs across the road to a wine shop and returns with a bottle of champagne. I’m disappointed, but Kalinin gives me a sly wink and approaches another table where several well-dressed Georgians are gathered. Wishing them a Happy New Year, he offers them the champagne. Then he returns to our table. In a few minutes the Georgians have sent over two bottles of champagne, a half-litre of vodka, and a dozen beers. We plunge into the beer and vodka. After a while we send the two bottles of champagne over to another group of Georgians. In an hour there are so many bottles on our table there’s not even room to rest your elbow.

Kalinin used to be a physics teacher He really does look like the former Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and he shrewdly exploits this resemblance.

“When I strike my pose on the Elbakidze bridge people stop and stare. Then they feel obliged to throw me a coin. You can find me on the bridge at any time; the cops leave me alone as long as I keep quiet. Trouble is, after I’ve had a few the urge comes over me to deliver a speech. My oratorical talent has landed me in the spets a few times.”

When night falls Kalinin shows me a place to sleep. Under one of Tblisi’s parks there is a cavern housing steam pipes that heat the city. In winter every railway prostitute, beggar, tramp and thief drifts to that cavern. Some are so weakened by illness and booze that they hardly ever leave the place. Others go about their business by day and gather again in the evening bringing food and drink. All night long the cavern rocks with songs, curses and fights.

It’s a murky place, lit only by candles stolen by church beggars. Rats scurry over the bodies of sleeping tramps. The floor is covered in crusts of bread, slimy pieces of rotting liver sausage and shattered eau de Cologne bottles. Wine and vodka empties are collected early in the morning. We sleep on cardboard discarded by furniture stores. On my second night one of the sick vagrants dies. We all leave the cavern, someone tips off the police and we make ourselves scarce while they come to collect the body.

Hippies have made their appearance in Georgia by this time and some of them try to join us. We despise them as dilettantes and kick them out of the cavern whenever they hang around for too long. Once in a while, however, some Tblisi artist or intellectual decides he want to experience life in the lower depths — and offers to pay for the privilege. Then we put on a real feast with songs and folk dances. We tramps know perfectly well what’s expected of us and earn the bottles that our visitors bring. Putting our arms around our free-spirited friends we spin endless yarns about our lives, sparing no harrowing detail.

One of our bacchanalia ends in a police raid. Nervous about entering our cavern, the cops send in dogs first. A tramp warns me that they’ll use CS gas to flush us out if we don’t leave of our own accord. As we emerge they throw us into waiting Black Marias. A cop grabs me but the confusion distracts him and I manage to slip away. I spend the rest of the night in the park and decide I will avoid the cavern in future.

The morning after the raid finds me wandering aimlessly down Plekhanov Avenue, hungry as a wolf-pack in winter. My head is a barrel of pain and grief; my brains splash about somewhere in its depths. I break into a cold sweat at the sudden hoot of a car. I feel that people on the other side of the street are watching me and whispering words of vicious condemnation. Penniless, I scour the beer-stalls but meet not a single acquaintance. I’m about to breathe my last yet I’m too scared to ask a stranger for a few kopecks. I slink along, keeping close to the wall and my eyes on the ground.

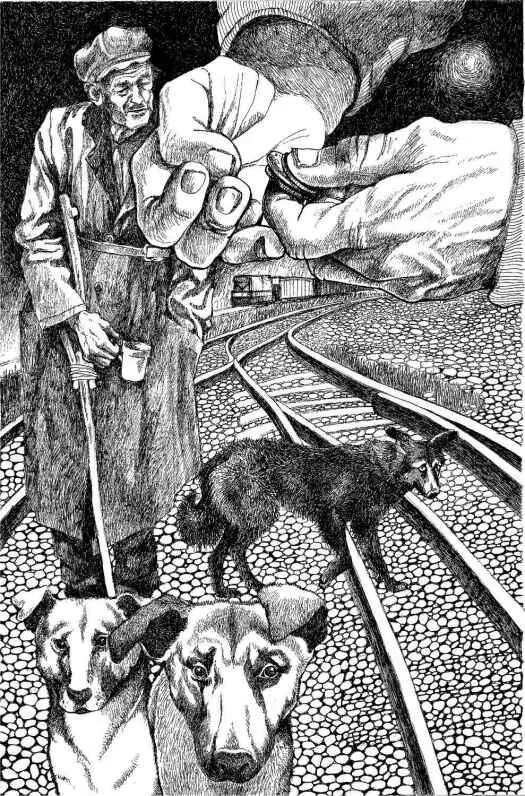

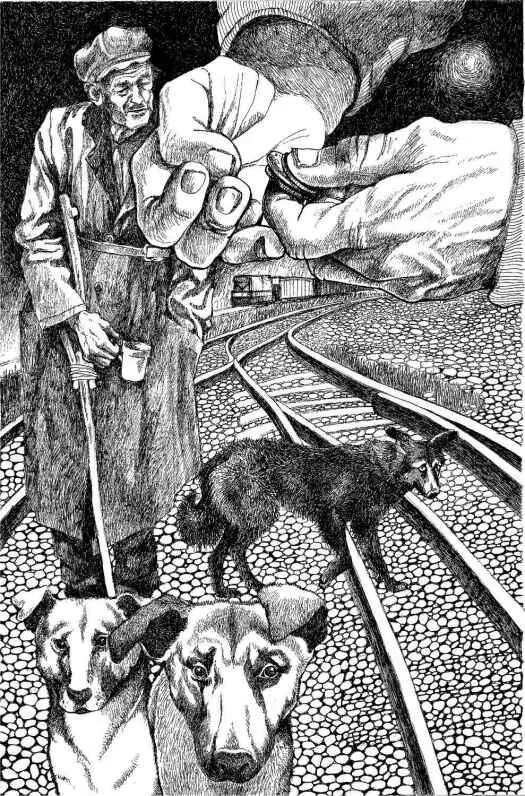

“Have you lost something?” says a voice above my head. A tall beggar stands with his back to the wall, propped up on two crutches.

“A purse — except I haven’t lost mine; I’m hoping to find someone else’s.”

“No one’s lost anything here today. That’s for sure. I’ve been here since morning.”

“Too bad,” I say, moving off.

“Stop!” he cries, “Can you help me?”

“How?”

“I need to buy a bottle but I can’t get to the shop.”

“My pockets are empty.”

“I’ve got the cash. I’ll wait for you in that little square over there.”

“Okay.”

“My hangover’s killing me,” he sighs.

“Mine too.”

He pours a pile of change into my hand.

“There’s more than enough for a bottle here,” I say.

“Buy two so you won’t waste time running back to the shop later.”

When I come out of the shop I see my saviour approaching the square, thrusting his crutches forward and dragging his paralysed body in their wake. I join him and we introduce ourselves. His name is Borya and he comes from Leningrad.

I discover that Borya is no drinker and only sent me for the wine because he guessed the state I was in. He drinks a glass to be sociable but refuses a refill.

“I’ve been paralysed since I was a student. I jumped from a train to avoid the ticket collector. If he’d reported me for travelling without a ticket the college would have cut off my grant. I had no family to support me. Since then I’ve been all over Russia. Once in a while the police pick me up and send me to an invalid home but I always run away. I arrive in some town or other and don’t leave it until I’ve collected 1000 roubles.”

“And then?” I ask.

“I bury them and go on to another town.”

“Are you trying to save a lot of money — for retirement perhaps?”

“No. It isn’t the money itself I need. I give away most of what I collect.”

“But why d’you live like this? You stand the whole day long at your pitch, collecting money. You don’t drink, you don’t smoke and you give it all away?”

“The money is not the most important thing. I make people happy.”

“How?”

“Imagine, I am standing on my pitch, virtually a corpse. A man goes by. I don’t know anything about him. Perhaps he’s a cruel person who beat his wife that morning. I’ve never seen him before and I’ll probably never see him again. He notices me, fumbles in his pocket, finds a three-kopeck piece that’s no use to him and chucks it into my cap. To me those three kopecks are nothing, but I’ve done something for that man.”

“What have you done?”

“I’ve caused him to do good. When he passes on down the road he is a different person, although he may not know it himself. Even if he gave me the money automatically, without thinking, he’s become a slightly better person.”

I stare at Borya, as stunned as a bull in a slaughterhouse. He laughs. “I can see that you’re not yourself yet. Here’s some more money. I’m going to work. Meet me in Gorky Park this evening?”

“Agreed.”

Borya pours some change into my hand, then he stands up. His body swaying like a pendulum, he returns to his pitch.

Anxious to continue our conversation, I do as Borya suggests and make for the park. As I near his pitch I cross to the other side of the street to pass unnoticed in the throng of pedestrians. The sight of me might remind Borya of his kindness; he’s not in need of my gratitude.

Picking up a bottle of Imereti wine along the way, I choose a far bench in the park where I can sit hidden behind some bushes. From time to time I take a slug of wine, trying to maintain myself on that blissful cusp between sobriety and drunkenness.

Long-suppressed thoughts churn in my mind: ‘Who am I?’ An alcoholic and a tramp. But I’m no white raven; half the country are alcoholics. Our alcoholics outnumber the populations of France and Spain combined. And that’s only the men. If you count women too you have to add on all Scandinavia and throw in Monaco for good measure.

Читать дальше

![Геннадий Марченко - Перезагрузка или Back in the Ussr. Книга 1. [СИ]](/books/53319/gennadij-marchenko-perezagruzka-ili-back-in-the-uss-thumb.webp)