I step forward.

“You will help in the library.”

I am lucky to get such a cushy job. In the morning I hand out letters and in the evening prisoners come for books and newspapers. ‘Soviet Woman’ is especially popular. Pictures of pretty women adorn walls and lockers. The prisoners replace them as soon as the guards tear them down. Convinced that the KGB checks which books they borrow, some zeks take out all 40 volumes of Lenin’s collected works.

My days pass easily enough; the only problem is the camp storekeeper, a former colonel, who keeps dropping into the library. This man destroys any lingering respect I might have for epaulettes: only in Russia could such an utterly stupid man have risen to such a high rank. His self-regard is so absolute it shocks me. He shows me the book he is writing. Life is not a Bed of Roses describes his life from birth to prison camp. In his childhood he was the top student, he ran the fastest and jumped the highest. In his youth he was more handsome and intelligent than his peers, in the army braver than his comrades-in-arms. His wife was the regimental beauty; he killed her from jealousy.

Our literary journals have already rejected the first volume of the colonel’s work; he assumes this is because it contains grammatical errors. Now he wants my help with corrections. I try to excuse myself, saying I’m not very literate, but he persists. In the end I give in. The task oppresses me but I haven’t got the courage to tell the colonel the truth.

A fellow prisoner named Oleg comes to my rescue. He is an intelligent lad who dropped out of university. We become friends and spend all our free time together. He helps me proofread the colonel’s book and we laugh over it together.

The library is stocked with classics and Dostoevsky’s works are constantly borrowed, especially Crime and Punishment . But the zeks are only attracted by the title. and return the book disillusioned, having failed to understand its archaic language. I try to warn them in advance: I don’t believe that someone of forty can suddenly become converted to Dostoevsky.

I can’t work out why the correspondence of our greatest authors should be in such constant demand. I’ve read Blok’s letters and was disappointed — and I’m more educated than most. One prisoner after another borrows Turgenev’s letters to Pauline Viardot. Old editions of local papers are also in heavy demand. Finally Oleg explains the mystery.

“Until last year petitioners for divorce had to make an announcement in their local papers. For example: Citizeness Ivanovna, Anna Semyonova, born 1942, living at 5, Sadovaya Street, has initiated divorce proceedings…

“Prisoners note down the names and addresses of divorced women and then they copy out Turgenev’s letters. Imagine how citizeness Ivanovna feels. She is alone after kicking out the husband who sold all her furniture for drink. Suddenly she receives a letter from an unknown admirer! And written in such effusive language that it makes her head spin. She replies and thus she becomes what we call an external student. Yura and Fedka each have three external students. They sometimes get parcels. There’s a woman in our street at home who married a prisoner after she became his external student.”

“But can’t they see from our address that this is a camp?”

“The zeks say they are working in a secret military plant, which is why the address is just a number. I am sure many women guess the truth but all the same they continue to write. It’s better to receive a letter than nothing at all. Remember the joke about two women friends who meet each other in the street? One says:

‘How’s the old man, drinking?’

‘Yes, the parasite.’

‘Knocking you around?’

‘Yes, the bastard.’

‘Well, you can’t complain, at least he’s in good health.’”

I laugh. Being a married woman in the happiest country in the world is better than being divorced, widowed or single. “Don’t you have an external student?” I ask Oleg.

“I don’t need one. My own wife’s enough. She had me arrested for beating her up. At my trial she pleaded with the judge to let me off but that only annoyed him.

“Lily was the most beautiful girl in town, but everyone despised her because she was born in prison. Her mother came from the Moscow intelligentsia and her father was an army officer, Polish I think. He was shot after the war as a cosmopolitan. After her release from jail Lily’s mother got a minus 20 [20] This meant she was prohibited from living in the 20 largest cities in the USSR.

so she ended up in Astrakhan.

“Lily’s mother was a proud and defiant woman. The locals called her a prostitute. You know what it’s like — a single mother coming out of prison, and to make it worse she was a member of the intelligentsia. Lily was a tough kid, always hanging around with the boys and baiting the teachers. She would start a fight for the slightest reason. She often won too, despite her size.

“Soon after they locked me up Lily had our daughter, Sveta. When she wants to see me she comes to the camp, sets Sveta down outside the Godfather’s office and runs away. Then she phones up and demands my release. Sveta screeches like a stuck pig, the guards can do nothing with her and in the end they give us a special visit. Then Lily takes Sveta away until the next time she decides she wants a visit. If he had the powers the Godfather would probably have released me by now.”

The library is separated from the camp schoolroom by a thin partition. School is compulsory for all those under sixty who have not completed the seventh class. Those who refuse have parcels and visits withheld. Teachers are civilian volunteers. The sound of these lessons keeps Oleg and me entertained as we work.

“Masha goes to the shop,” the teacher’s voice reads out.

Some wit remarks: “It’d be better if she came to see us.”

Ignoring him, the teacher’s voice continues: “Who can tell me which is the subject of the sentence?”

Silence.

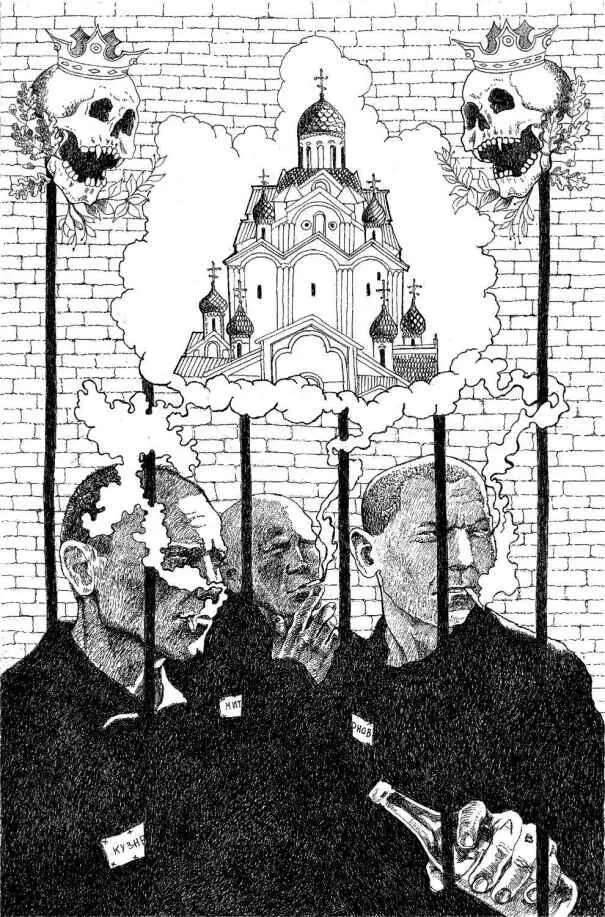

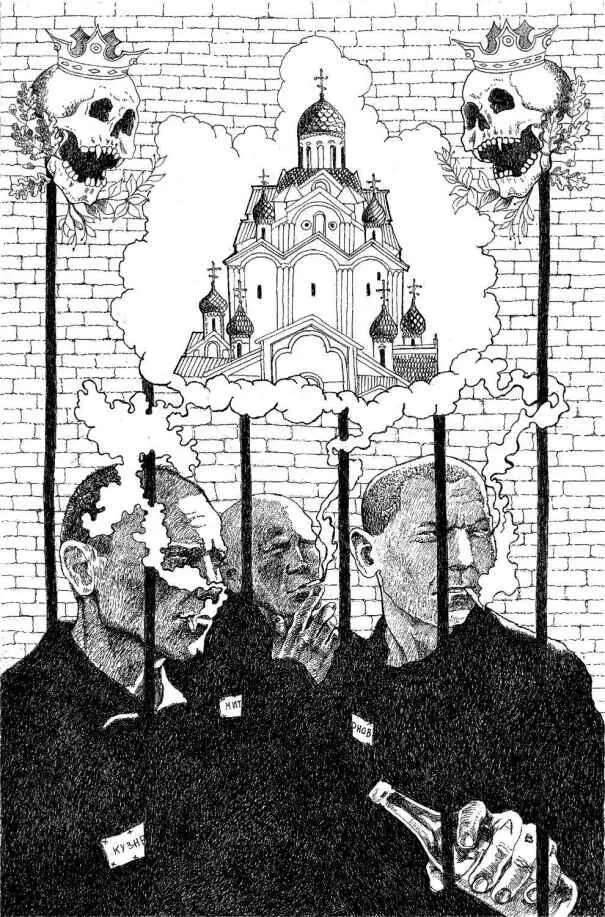

“You, Kuznetsov, come up to the board, please.”

“What’s the point if I don’t know the fucking answer?” grumbles Kuznetsov, but we hear the scrape of his bench.

“Which word is the subject of the sentence?”

After some thought Kuznetsov answers: “Er, Masha?”

“Correct! and which is the verb?”

“Um, ‘shop’?”

“No. Anyone else?”

“Of course it is ‘goes’ but we would say: ‘staggers’” another voice pipes up.

“How do you mean ‘staggers’?” asks the teacher.

“Well, Masha’s obviously got a hangover and is going for a bottle.”

“No not, ‘staggers’ but ‘waddles,’ because of the huge arse on her.”

At that point everyone throws themselves into an impassioned discussion about Masha’s qualities and failings, her physique and her temperament.

When exams take place candidates spill out of the classroom into the library looking for us. Together we help them solve problems and correct their written mistakes. The teacher does not try to stop us. The more who pass the better it looks for him.

Our camp has a technical school which is supposed to give inmates skills that will deter them from the path of crime. The yard outside the school is full of farm machinery waiting to be repaired. It is protected from the weather by tarpaulin and guarded by an old man who was sentenced for killing his wife. In her death struggle she hit him so hard with an iron that he has a dent in his cranium the size of a fist. The blow altered his mind.

Читать дальше

![Геннадий Марченко - Перезагрузка или Back in the Ussr. Книга 1. [СИ]](/books/53319/gennadij-marchenko-perezagruzka-ili-back-in-the-uss-thumb.webp)