Edward Lucas

DECEPTION

The Untold Story of East-West Espionage Today

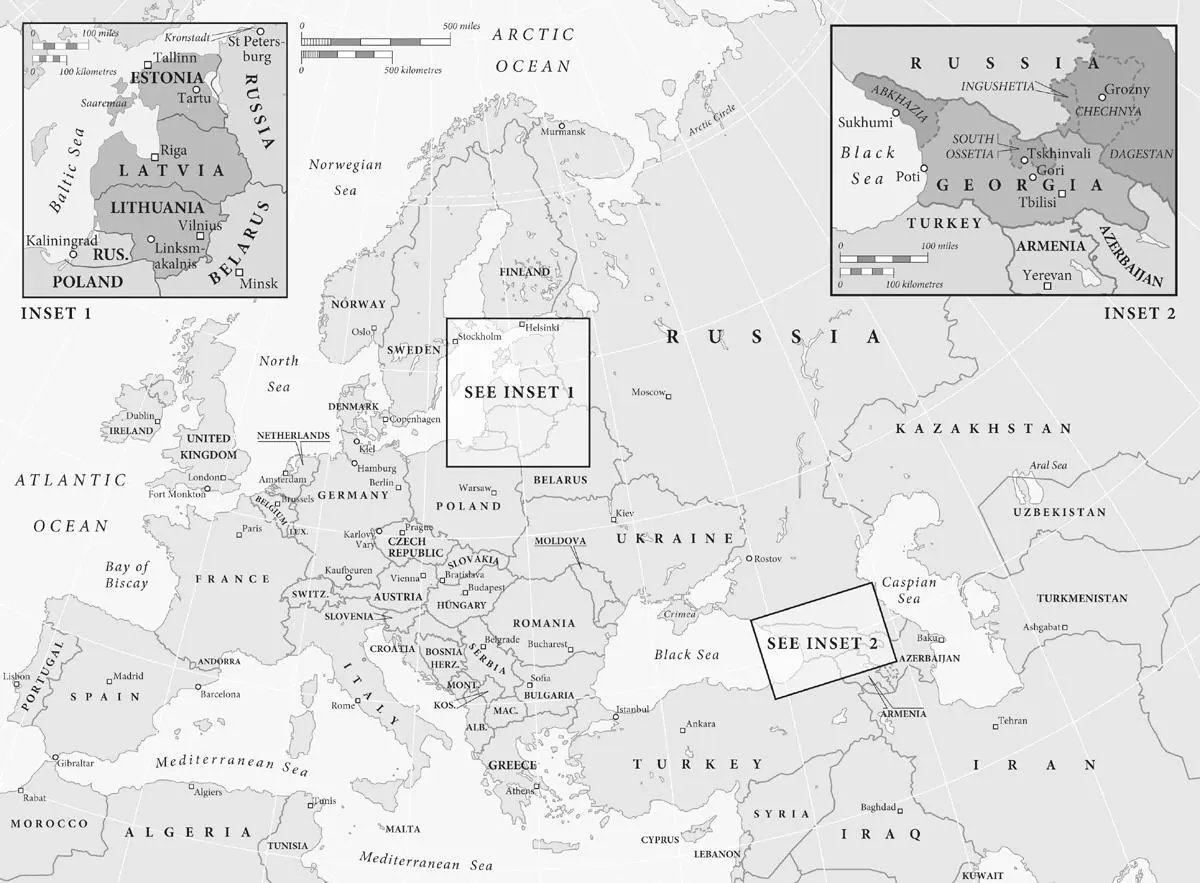

The cold breath of the communist secret police state blighted countless lives behind the Iron Curtain. But it also touched my own childhood in 1970s Oxford. Olgica, our Yugoslav lodger, had an exciting secret: Uncle Dušan. The poet Matthew Arnold described Oxford as ‘home of lost causes, and forsaken beliefs, and unpopular names, and impossible loyalties’. In Dušan’s case, this was partly right: his surname (like those of most East European émigrés) if not exactly unpopular, was certainly baffling to British eyes and ears. I recall him as a glum, shadowy figure, with plenty to be glum about. His cause seemed irretrievably lost. He was a hero in his own twilight world, but in post-war Yugoslavia the authorities denounced anti-communists like him as criminals and traitors. [1] a An official of the pre-war royalist government, his side had lost out to the communists in the internecine strife in wartime Yugoslavia. There (as in much of Eastern Europe) the Second World War had been a fight between not two sides, but three. The Nazis had battled with communist partisans and the royalist Chetniks, who loathed each other as much as they hated the invaders. When the Germans lost, the communists (who had enjoyed strong backing from Britain and America as well as from the Soviet Union) won their civil war against the much weaker royalists, and labelled them as fascist collaborators.

Many perished in mass graves or in the torture cells of the secret police. Dušan was one of the lucky ones. He had escaped to Britain, to a humble job as a mechanic and life in Crotch Crescent, a drab street in Oxford’s outskirts – a sad comedown for someone who in pre-war Yugoslavia had been a high-flying young civil servant.

But in one respect, Dušan did not fit Arnold’s dictum. Despite his disappointments, he had not forsaken his beliefs: communism was evil and the people who ruled his homeland were usurpers. In fact, Yugoslavia’s independent-minded communists had become mild by comparison with the much tougher regimes of the Soviet bloc. But they were still ruthless in their treatment of dissenters, particularly those in contact with anti-communists abroad. Olgica’s family maintained, at great risk, secret links with émigré relatives, flatly denying all knowledge of them under interrogation from the secret police. In Oxford, she visited her uncle each weekend. Had the authorities at home known that she was hobnobbing with a dangerous anti-communist émigré, her father’s glittering medical career (which had even brought him, briefly, to Oxford) would end; her own future (she had stayed on to finish her schooling) would be jeopardised too. It could even be dangerous for her to return home, leaving her stranded in Britain as a teenage refugee.

My own childish preoccupations blundered into this grown-up world. Even before Olgica’s arrival, my boyhood obsession had been Eastern Europe. I would spend hours looking at dusty atlases and reading about the vanished kingdoms and republics of the pre-communist era, with their long-forgotten politicians, quaint postage stamps and exotic languages. Now behind the Iron Curtain, they seemed as distant and unreal as Atlantis. In my early teens I needed an example of communist propaganda for a school history project and decided to write to the Yugoslav embassy in London, asking for an official statement of how their government saw their defeated royalist rivals. That would, I thought, sit nicely alongside the other exhibits I had already assembled, including a passage from Winston Churchill’s history of the war, a poignant account of life in Cambridge by the exiled Yugoslav boy-king Peter, and a sizzling history of a British military mission to his doomed soldiers, the Chetniks. 1

I proudly announced my plan. To my consternation, Olgica turned white. My mother took me aside: didn’t I understand that the Yugoslav embassy in London would at once hand over this letter to the secret police? (With its sinister-sounding acronym UDBA, the Uprava državne bezbednosti or Department of State Security was the bane of the regime’s critics at home and abroad). It would be obvious that my childish enquiry came from the very Oxford address at which the daughter of a top Yugoslav paediatrician was living while completing her A-levels. It was bad enough that the UDBA would instantly suspect her of propagandising about the royalist past – a crime in Yugoslavia. Worse, it would start checking up on her family history and might then discover her carefully concealed ties to the notorious inhabitant of Crotch Crescent. Her life could unravel in an instant.

This trivial episode taught me important lessons – albeit in politics not history. First, that the power of the communist state was based on the relentless, intrusive, bureaucratic reach of the security and intelligence services, and their capacity to ruin the lives of those who displeased them. Second that these agencies’ reach extended far beyond their own grim dominions – even to the seemingly safe and secure world of an English university town. The extraordinary idea that my actions could put me under scrutiny by hostile foreign officials sparked an interest that has gripped me for decades. In the years that followed I devoured spy literature, from defectors’ memoirs to John le Carré’s novels. I tracked down retired spies and quizzed them. I also kept a beady eye on contemporaries who were offered jobs by MI6, as Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, SIS, is colloquially known. [2] b Based since 1995 in a green-glazed ziggurat on the southern bank of the Thames, the Secret Intelligence Service is informally called MI6; semi-official names include ‘the Friends’ or more formally ‘Other Whitehall Agencies’. Its employees usually refer to ‘the Office’; outside contacts may coyly call it ‘the Firm’.

Even without knowing much about the intelligence world I was struck by the clumsiness of those approaches: on the same day a crop of identical government-issue buff envelopes would arrive in student pigeonholes. Some recipients ignored the strictures to keep silent. A friend even framed the letter and put it in his lavatory, so his friends could appreciate the unconvincing letterhead and the strangulated wording of the offer: ‘From time to time opportunities arise in government service overseas of a specialised and confidential nature.’ For those who did apply, the clumsy efforts of the vetting officers (also accompanied by dire warnings about secrecy) were similarly corrosive of confidence in the spooks’ world-view. Did it really matter in the struggle against the Soviet empire, I wondered, if Tom had gay flings, if Dick smoked dope or if Harriet had a boyfriend in the Socialist Workers’ Party?

I reckoned I could do more good on the outside, and searched for any East European cause that would accept my help. Inspired by my father, who smuggled books to fellow-philosophers persecuted in Czechoslovakia, I helped organise a student campaign to support Poland’s Solidarity movement, crushed by martial law in December 1981. I waved placards outside embassies and wrote letters of protest on behalf of political prisoners. I studied unfashionable languages such as Polish, and practised them by befriending bitter old émigrés in the dusty clubs and offices of west London – the world of le Carré’s Estonian ‘General’ in Smiley’s People . 2Like the spy author’s fictional émigrés, these real-life ones had been sponsored by Britain’s spooks, then betrayed and dumped. I did not know then the full extent of the fiasco of Operation Jungle, which I detail in chapter 9.

Читать дальше