Florida v. Riley was one of the last cases that William Brennan would hear. His dissent reads like a man with outrage fatigue. “The plurality undertakes no inquiry into whether low-level helicopter surveillance by the police activities in an enclosed backyard is consistent with the ‘aims of a free and open society,’” Brennan wrote. He then returned to a running theme in his dissents in such cases—that the Court was creating a drug war exception to the Fourth Amendment. He noted that the plurality opinion suggested that the Court might have viewed the case differently if the officer had seen “intimate details” from the helicopter. “Where in the Fourth Amendment… [is there] a requirement that the activity observed must be ‘intimate’ in order to be protected by the Constitution?” Brennan wrote. “If the Constitution does not protect Riley’s marijuana garden against such surveillance, it is hard to see how it will prohibit the government from aerial spying on the activities of a law-abiding citizen on her fully-enclosed outdoor patio.” Brennan then quoted from a law review article by Fourth Amendment scholar Anthony Amsterdam: “The question is not whether you or I must draw the blinds before we commit a crime. It is whether you and I must discipline ourselves to draw the blinds every time we enter a room, under pain of surveillance if we do not.” Fittingly, Brennan closed with a passage from George Orwell’s 1984: “In the far distance, a helicopter skimmed down between the roofs, hovered for an instant like a bluebottle, and darted away again with a curving flight. It was the Police Patrol, snooping into people’s windows.” 54

The Court’s last real civil libertarian retired a month later.

The Numbers

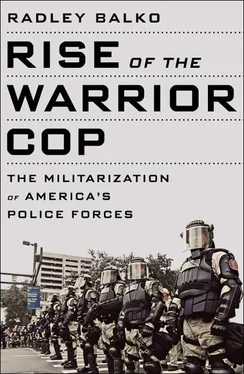

Number of drug raids conducted in 1987 by the San Diego Police Department: 457

Number of drug raids conducted in 1987 by the San Diego Police Department: 457

Number of drug raids conducted by the Seattle Police Department in 1987: approximately 500

Number of drug raids conducted by the Seattle Police Department in 1987: approximately 500

Value of the assets in the Justice Department’s forfeiture fund in 1985: $27 million

Value of the assets in the Justice Department’s forfeiture fund in 1985: $27 million

Value of the assets in the Justice Department’s forfeiture fund by 1991: $644 million

Value of the assets in the Justice Department’s forfeiture fund by 1991: $644 million

Percentage of US cities with populations over 50,000 that had a SWAT team in 1982: 59 percent

Percentage of US cities with populations over 50,000 that had a SWAT team in 1982: 59 percent

… in 1989: 78 percent

… in 1995: 89 percent

Percentage of those SWAT teams that trained with active-duty military personnel: 46 percent

Percentage of those SWAT teams that trained with active-duty military personnel: 46 percent

Average annual number of times each of those SWAT teams was deployed in 1983: 13

Average annual number of times each of those SWAT teams was deployed in 1983: 13

… in 1986: 27

… in 1995: 55

Percentage of those deployments in 1995 that were only to serve drug warrants: 75.9 percent

Percentage of those deployments in 1995 that were only to serve drug warrants: 75.9 percent

Percentage of cities with populations between 25,000 and 50,000 that had a SWAT team in 1980: 13.3 percent

Percentage of cities with populations between 25,000 and 50,000 that had a SWAT team in 1980: 13.3 percent

… in 1984: 25.6 percent

… in 1990: 52.1 percent

Average annual number of times each SWAT team in a city with a population between 25,000 and 50,000 was deployed in 1980: 3.7

Average annual number of times each SWAT team in a city with a population between 25,000 and 50,000 was deployed in 1980: 3.7

… in 1985: 4.5

… in 1990: 10.3

… in 1995: 12.5 55

CHAPTER 7

THE 1990S—IT’S ALL ABOUT THE NUMBERS

Why serve an arrest warrant to some crack dealer with a .38? With full armor, the right shit, and training, you can kick ass and have fun.

—US MILITARY OFFICER WHO CONDUCTED TRAINING SEMINARS FOR CIVILIAN SWAT TEAMS IN THE 1990S

The 1990s kicked off with a familiar debate: Congress wanted the military to be more involved with the drug war. At the urging of drug czar William Bennett, the Bush administration was waging aggressive antidrug campaigns in Latin America, the most notable of which was the 1989 invasion of Panama to capture military governor Manuel Noriega, who was wanted in the United States for drug trafficking. That action was made possible by an opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel; issued a month before the invasion, the opinion concluded that the Posse Comitatus Act didn’t apply outside of US borders. Members of Congress followed by calling for more policelike actions by US troops to arrest suspected drug dealers in other countries.

Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney had led the Republican push for the 1988 drug bill that included the death penalty for drug dealers and widespread use of the military for drug interdiction. One Cheney lieutenant, Assistant Secretary of Defense Stephen Duncan, said at a 1991 conference, “We look forward to the day when our Congress… allows the Army to lend its full strength toward making America drug free.” 1Even some career military officials were starting to come around, mostly out of fear that after the fall of communism in Europe, the military could suffer a loss of stature if it didn’t find a new enemy to engage. “The Soviet threat is being taken away from us,” one DC military scholar explained to the Chicago Tribune . “The Department of Defense had better develop some social-utility arguments that match the requirements of the American people.” 2

Even Cheney drew the line at using active-duty troops for civilian policing inside of US borders—but that didn’t seem to stop it from happening. The Christian Science Monitor reported in August 1990 that 58 active-duty Army troops had assisted in Operation Clean Sweep, the latest marijuana eradication program in northern California, and another 225 infantry soldiers and aviators and nine UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters from Fort Lewis, Washington, helped find pot plants in Operation Ghost Dancer in Oregon. 3

The early 1990s also saw a new push to find a greater drug war role for the National Guard. “When you have the equipment and trained personnel, you might as well put them to work,” said Rep. Nick Mavroules, a Massachusetts Democrat serving on the House Armed Services Committee. When asked about the traditional line separating the military from domestic policing, Republican representative Duncan Hunter of California snapped, “It depends on which is more sacred, that line or your children’s lives.” One influential Capitol Hill staffer gave an especially confused justification. “We have to take some kind of action, not because it’s going to solve the problem… but because of the fact that the druggies have gotten their fingers into an awful lot of pies.”

Part of the reason why so many politicians were enthusiastic was that National Guard involvement brought increased funding to their states. In 1989, the first year of the program, Congress appropriated $40 million for the National Guard’s drug interdiction efforts. The next year funding jumped to $70 million. Two years later it was up to $237 million. 4Any congressman or senator who opposed Guard troops fighting the drug war out of principle risked leaving his state out of the bounty. In Washington State, for example, the state’s National Guard received just under $1 million for antidrug operations. The next year the state’s congressional delegation signed a letter requesting seven times that amount.

Читать дальше

Number of drug raids conducted in 1987 by the San Diego Police Department: 457

Number of drug raids conducted in 1987 by the San Diego Police Department: 457