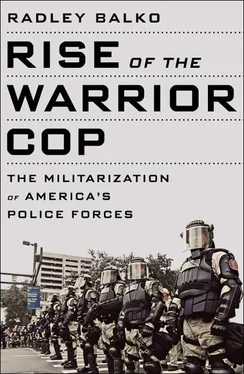

“I’ve investigated some tough people. A lot of drug dealers, a lot of gangsters. I never had a case where knocking, announcing, and waiting for someone to come to the door created a problem,” Jones says. Now retired, Jones’s two decades of experience as a drug cop have since turned him into a vocal critic of police militarization and the drug war in general.

“I was already concerned with this militarizing of cops in San Jose. I don’t recall ever using a ‘no-knock’ warrant in my career,” Jones says. “But when I got to DEA, I noticed a slow progression in that direction. Guys would say, ‘Oh, I heard a toilet flush,’ or, ‘I heard someone running in the house,’ which they’d use as an excuse to break in after knocking instead of waiting for someone to answer. Eventually, the pause between the time they’d knock and the time they’d break down the door was so short that they weren’t giving anyone time to get to the door to let them in—even if the suspect wanted to. And most of them did. I guess after I left the task force, they got to the point where they’d sometimes just not bother knocking at all.”

The MERGE lieutenant eventually backed down and told his team to change into regular police uniforms. They served the Hell’s Angels warrants by knocking, announcing themselves, and then waiting to be let in. They didn’t break down a single door. The suspects went peacefully. And the search turned up plenty more evidence of a methamphetamine operation.

Later, Jones’s supervisor tracked him down back at the office. The MERGE lieutenant had complained. Jones explained his position. His boss seemed to agree, but added, “You won the argument this morning, but you’re going to lose the battle. These guys got new toys. They want to use them.” 88

BY THE SECOND HALF OF THE 1970S, THE LAW-AND-ORDER hard-liners had temporarily been stalled. President Jimmy Carter took a much less aggressive approach to the drug war than Nixon had. The country took a break from seven years of continual drug war and police power escalation, at least at the federal level.

But Sam Ervin’s defeat of the no-knock raid was in many ways merely symbolic. It was never clear that federal agents actually needed the law to conduct such raids in the first place. Indeed, by the early 1980s they were using the tactic again, without any new federal law to officially reauthorize the practice. But Ervin’s moral leadership on the issue was important in halting the spread of a dangerous tactic, even if only temporarily. In his autobiography, Ervin writes, “I was convinced that we must not sacrifice the proud boast of our law that every man’s home is his castle on the altar of fear.” 89

The lull in the fighting didn’t last long. Before Carter left the White House, he’d face allegations that pot-smoking was common among his staff and that two senior-level aides were cocaine users—and that one of them was his drug czar. The Reagan administration would soon come in to staff the drug policy positions with hardened culture warriors.

Ervin’s wins were important, but ultimately ephemeral. The drug war and police militarization trends were about to merge. By the time Sam Ervin died in April 1985, the California National Guard was sending helicopters to drop camouflage-clad troops into the backyards of suspected pot growers in Humboldt County; the Justice Department was wiretapping defense attorneys; and Daryl Gates was using a battering ram affixed to a military-issue armored personnel carrier to smash his way into the living rooms of suspected drug offenders.

The Numbers

Value of the property that Nixon claimed in 1972 was stolen each year by heroin addicts: $2 billion

Value of the property that Nixon claimed in 1972 was stolen each year by heroin addicts: $2 billion

… claimed by Minnesota senator George McGovern: $4.4 billion

… claimed by Nixon administration drug treatment expert Robert DuPont: $6.3 billion

… claimed by Illinois senator Charles Percy: $10 billion–$15 billion

… claimed by a White House briefing book on drug abuse distributed to the press: $18 billion

Total value of all reported stolen property in the United States in 1972: $1.2 billion

Total value of all reported stolen property in the United States in 1972: $1.2 billion

Number of burglaries committed by heroin addicts each year, per Nixon administration claims: 365 million

Number of burglaries committed by heroin addicts each year, per Nixon administration claims: 365 million

Total number of burglaries committed in the United States in 1971: 1.8 million

Total number of burglaries committed in the United States in 1971: 1.8 million

Number of SWAT teams in the United States in 1970: 1

Number of SWAT teams in the United States in 1970: 1

Number of SWAT teams in the United States in 1975: approximately 500

Number of SWAT teams in the United States in 1975: approximately 500

Total number of federal narcotics agents in 1969: 400

Total number of federal narcotics agents in 1969: 400

Total number of federal narcotics agents in 1979: 1,941

Total number of federal narcotics agents in 1979: 1,941

Peak year for illicit drug use in America: 1979

Peak year for illicit drug use in America: 1979

Total number of no-knock search warrants carried out by the federal government from 1967 to 1971: 4

Total number of no-knock search warrants carried out by the federal government from 1967 to 1971: 4

Number of no-knock search warrants carried out by ODALE during its first seven months of existence in 1972: more than 100 90

Number of no-knock search warrants carried out by ODALE during its first seven months of existence in 1972: more than 100 90

CHAPTER 6

THE 1980S—US AND THEM

It now appears that… victory over the Fourth Amendment is complete.

—WILLIAM BRENNAN

William French set the tone for the Reagan administration early on. In one of the first cabinet meetings, the new attorney general declared, “The Justice Department is not a domestic agency. It is the internal arm of the national defense.”

This would be a rough decade for the Symbolic Third Amendment. Reagan’s drug warriors were about to take aim at posse comitatus , utterly dehumanize drug users, cast the drug fight as a biblical struggle between good and evil, and in the process turn the country’s drug cops into holy soldiers.

French surrounded himself with a crew of prosecutors who called themselves the “hard chargers.” One was Rudy Giuliani, a rising star brought to Washington by French after he had racked up some impressive federal drug prosecutions in New York. In an interview with the journalist Dan Baum, Lowell Jensen, another of French’s advisers, said that the first task French assigned Giuliani was to survey US attorneys, cops, and prosecutors across the country about how the federal government could get more involved in fighting local crime. The overwhelming answer French got back was the same answer John Mitchell got when he posed the same question to his aides in the early days of the Nixon administration: launch a war on drugs.

So they did, with some sweeping new policies. One of the most significant new policies came thanks to a fortuitous bit of timing. Shortly after Reagan took office, the General Accounting Office (GAO) released a report, commissioned by Democratic senator Joe Biden of Delaware a year earlier, on the use of civil asset forfeiture. Civil forfeiture was a concept that had a long tradition in English common law. Under the law of deodands —Latin for “given to God”—anytime a piece of property caused a death, the property itself could be deemed guilty of the crime, at which point it or its value had to be forfeited over to the Crown. In colonial times, the concept was extended to allow the state to seize and confiscate ships that had been used to smuggle contraband. The Crown’s abuse of the practice is often credited with inspiring the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition on the taking of property without due process. 1

Читать дальше

Value of the property that Nixon claimed in 1972 was stolen each year by heroin addicts: $2 billion

Value of the property that Nixon claimed in 1972 was stolen each year by heroin addicts: $2 billion