It was not an uncommon sentiment in the military at the time. When the US Army made its Basic Field Manual available to the public for the first time in 1935, it included a section on strategies for handling domestic disturbances. 14The recommendations were unsettling. The guide suggested firing into crowds instead of firing warning shots over their heads, and it included instructions on the use of chemical warfare, artillery, machine guns, mortars, grenades, tanks, and planes against American citizens. 15Another military manual defined democracy as “a government of the masses…. Results in mobocracy… demagogism, license, agitation, discontent, anarchy.” Newspaper editorials and political advocacy groups lashed out, arguing that the US Army had essentially published a how-to guide for waging war on its own people. The military responded, with some justification, that the manuals made no mention of when or under what circumstances these tactics—which were tactics of last resort—should be used in domestic disturbances. 16

The backlash showed that there was still an ample reserve of public support for the broader principles behind the Third Amendment. The outrage grew loud enough that in early 1936, Army chief of staff general Malin Craig retracted the manual and ordered it removed from circulation. By 1941 much of the offending language had been either removed or replaced with instructions emphasizing the use of nonlethal force. 17The military had overstepped, and when it was held to account, it retreated: the instructions were revised to strike a more appropriate tone, one more in line with its proper relationship with the American citizenry.

World War II put an end to concerns about Communists and anarchists. Protests died down, and with them the need to send troops to dispel those that got out of hand. But the period wasn’t entirely calm. Racial tension mounted in some cities as black servicemen returned from the war to the same segregation, poverty, and limited opportunity they had experienced before they left. In Los Angeles, clashes between stationed Navy and Marine servicemen and the city’s Latinos boiled over into the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943. Riots also broke out in Detroit, Chicago, and Harlem, but only the Detroit riots required federal intervention.

The first decade after the war was even quieter, as the economy boomed and veterans settled down with good jobs to start families. But things were about to change. Civil rights victories would inspire revolt in the South, and the counterculture and antiwar protesters were coming.

THE NEW ERA BEGAN IN LITTLE ROCK IN 1957. THE SUPREME Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education animated civil rights groups and angered segregationists. When nine black students attempted to attend classes at Central High School on September 4, Gov. Orval Faubus sent Arkansas National Guard troops to prevent them from entering the building.

There had been a number of incidents leading up to Little Rock in which efforts to integrate public facilities had also been met with violence. Until Little Rock, President Dwight Eisenhower had opposed sending federal troops to force integration, and he initially resisted sending soldiers to Arkansas as well. 18Instead, he first held a face-to-face meeting with Faubus, thinking he could convince the governor to stand down. Faubus responded by pulling the tr

oops entirely, allowing an angry mob to force the black students to withdraw from class on September 23. 19Two days later, Eisenhower ordered troops from the 101st Airborne Division to escort the students to school. The soldiers were soon replaced by troops from the Arkansas National Guard, which Eisenhower had federalized. Those units stayed until the end of the school year. Beginning the following year, federal courts supervised the Little Rock school system’s compliance with Brown v. Board of Education until 2007. 20

Eisenhower’s initial reluctance to send troops to Little Rock is often seen as a stain on his record, perhaps justifiably so. But Eisenhower had ridden alongside MacArthur at the Bonus March. In fact, he had advised MacArthur that there was something unseemly about the military’s highest-ranking officer leading a charge against a citizen protest. It’s possible that Eisenhower was reluctant to send troops south in 1957 because of what he saw in 1932 and the resulting public backlash. Eisenhower eventually did send troops into Little Rock because, he said, federal law was being “flouted with impunity” and he feared that the South could slip into anarchy if something wasn’t done. He waited until he felt that sending in troops was his only option. Though an argument could be made that he waited too long, his actions also kept with the protections built into the Insurrection Act. 21

By the 1960s, the civil rights, counterculture, and antiwar movements would be in full swing, leading the government to call repeatedly on the National Guard and occasionally on US troops to keep order in urban areas. Still, the principle of keeping the US military out of law enforcement remained largely intact. Despite the best efforts of too many politicians, the public still tended to recoil at the idea of putting soldiers on city streets, even for a brief time, much less for day-to-day law enforcement.

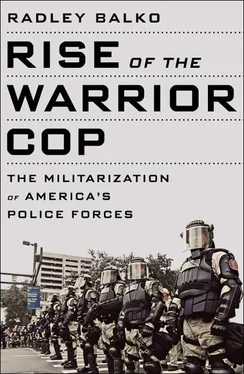

That’s the good news. The bad news fills most of the rest of this book. While as a nation we have mostly done a good job of keeping the military out of law enforcement, we’ve done a poor job, to borrow a bit of martial rhetoric, of guarding our flanks. The biggest threat to the Symbolic Third Amendment today comes from indirect militarization. Instead of allowing our soldiers to serve as cops, we’re turning our cops into soldiers. It’s a threat that the Founders didn’t anticipate, that nearly all politicians support, and that much of the public either seems to support or just hasn’t given much attention.

No one made a decision to militarize the police in America. The change has come slowly, the result of a generation of politicians and public officials fanning and exploiting public fears by declaring war on abstractions like crime, drug use, and terrorism. The resulting policies have made those war metaphors increasingly real.

CHAPTER 4

THE 1960S—FROM ROOT CAUSES TO BRUTE FORCE

Democracy means that if the doorbell rings in the early hours, it is likely to be the milkman.

—ATTRIBUTED TO WINSTON CHURCHILL

Early in the morning of March 25, 1955, narcotics agents in Washington, DC, arrested Clifford Reed on suspicion of distributing narcotics. Reed told a federal agent that he had purchased one hundred capsules of heroin from Arthur Shepherd, who was working for a drug dealer named William Miller. The agents recognized that they might be able to parlay a low-level arrest into a much larger bust.

Reed agreed to cooperate in a controlled drug buy, and at around 3:00 AM he and a federal agent posing as a buyer gave Shepherd $100 in marked bills to buy another one hundred heroin capsules. Shepherd then took a cab to the home of Miller, with the agents following. But the agent tracking Shepherd lost him when he exited the cab and entered Miller’s building. Afterward, DC city police stopped the cab that Shepherd was in and found the heroin he had just purchased—but the federal agents had failed to observe the actual drug buy.

In an attempt to salvage the bust, the federal agents returned to Miller’s apartment and knocked on the door.

Miller said, “Who’s there?”

Читать дальше