For these few, the normal quality scale didn’t apply. Was a 100-point wine some barrel-tasted, right-bank upstart anointed by a self-styled arbiter in Monkton, Maryland? No, for these people it was an 1865 Lafite, a 1900 Margaux, a 1945 Mouton, a 1947 Cheval Blanc. “People who haven’t tasted these wines should refrain from judging on a 100-point scale,” Scheuermann said. “They should judge up to 90 or 95. One hundred points means the greatest wines ever produced for us to taste. Boys and girls who haven’t tasted these should refrain from judging.” He paused, as it dawned on him how this sounded. “On the other hand, that’s arrogant.”

Others simply appreciated their experience for what it was and moved on to more commonplace wines. Talking about the rarities wasn’t just arcane, it was obnoxious and boring. People who had shared an intense experience they could discuss only with each other, they kept quiet. “The 1871 Yquem, my favorite, I drank four times,” Otto Jung recalled. “Only about fifteen people in the world have done that. You can’t talk to your normal friends about it.”

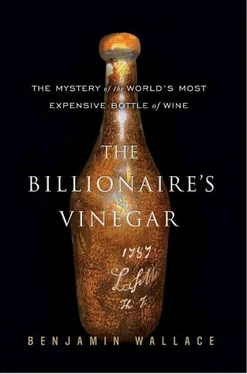

It appeared that the full truth about the Jefferson bottles would never be revealed. Thirteen years had passed since they first made news. Circumstantial arguments aside, there was no definitive proof that they had belonged to Jefferson, and none that they hadn’t. When it came to sensory evaluation, the authority on old wines, Michael Broadbent, had deemed the six he tasted to be authentic, while other tasters had expressed skepticism. A scientific test had established that at least one bottle contained young wine, but another test a year later had seemed, at least in the eyes of the wine media, to rebut the idea that all the bottles might be affected. The second test had also thrown into question who had tampered with the bottle from the first test. Every answer had given way to new questions. It seemed unlikely that another scientific test could break the tie. The most famous of the bottles had, after all, been compromised before the eighties were up, the Forbes bottle through its cork slippage, the Sokolin bottle by being broken at the Four Seasons. And the Jefferson bottles were so expensive as to create a strong disincentive for the owner of one, even if skeptical, to destroy it for the sake of… what? Barring an uncharacteristic revelation by Rodenstock, or the unexpected emergence of a previous owner of the bottles, the secret looked as if it would die with Rodenstock.

CHAPTER 17

KOCH BOTTLES

ON A WEDNESDAY IN SEPTEMBER OF 2005, NEARLY twenty years after the Forbes family made wine-auction history, their bottle reposed on lower Fifth Avenue, in a suite on the second floor of the Forbes Building. There, amid the hushed sounds of clicking keyboards and chirruping phones, the galleries’ staff was busy with its curatorial mission, which increasingly meant getting rid of things.

Fifteen years after Malcolm’s death, the Forbes children had deaccessioned many of their father’s collections in order to raise funds. In 1993 they auctioned off the Orientalist art that had adorned his palace in Tangiers. Over the next several years they sold his collection of toy soldiers, an Edward Hopper painting (to Steve Martin, the actor, for $10 million), and, through Christie’s, sixty-two American paintings and sculptures. At the time, the New York Times reported that, “given the Forbes provenance,” prices could greatly exceed estimates and quoted the chairman of Christie’s in America as saying, “We’re hopeful, but who knows? It’s a great name.” In 2002 the Forbeses sold a number of their historical manuscripts. Economic pressures that year also led to job and benefit cuts at the magazine, and in 2003, over the objections of Kip, his siblings sold off the Victorian painting collection he had lovingly assembled over many years. At the sale at Christie’s London, which Kip reportedly stayed away from because it would be “too sad,” a fan illustrated with a drawing by Charles Keene was snatched up by none other than Michael Broadbent, who had been collecting the nineteenth-century artist’s work since the 1950s. In 2004 the Forbeses sold off their most famous possession, a 180-piece collection of jeweled eggs and other objets from the House of Fabergé.

The Forbes brand continued to stand for expert collecting and connoisseurship. Forbes magazine published an annual collectors’ issue, and for the preceding three years the company had published a collecting newsletter. The articles didn’t shy away from the issue of counterfeit collectibles in general (“Spotting Fakes”), or fake wine in particular (“In Vino Falsitas,” “Château Faux”), but they did omit the Forbeses’ own susceptibility to being duped. The articles failed to note that a painting by the American artist William Aiken Walkers, Levee at New Orleans, which Kip Forbes had purchased for more than $50,000, had turned out to be a forgery.

Even now, their Jefferson bottle continued to pop up in the news and on Internet boards, both because twenty years on it still held its world record, and because it remained a compelling example for those who saw it as the ultimate in human folly. Just a month earlier, the London Times had recalled the bottle’s ignominious end in a squib headlined “Blunders of the World.”

On this day in September, Bonnie Kirschstein, who presided over the galleries, wore a black pantsuit. She reached into a box of pristine white cotton gloves, removed two, and put them carefully on her hands, pulling them snug. Then she moved toward a closed door. Standing squarely in front of a security keypad, making it invisible to anyone behind her, she punched in a code and turned the handle. The door opened.

Stepping inside, she flicked a switch, and fluorescents clicked on above her. It was a small, windowless room with a linoleum floor. The temperature and humidity were carefully controlled, and the air was cool and dry. To the right, reaching almost to the ceiling, stood four beige metal bookcases, the kind that have giant dials on the end and slide along tracks to make the most efficient use of limited space. Kirschstein went to the second-to-last case, turned the dial, and wheeled the unit toward the door, exposing the last case.

The room was a way station for objects not yet cataloged, in between exhibits, or waiting to be moved to a deep-storage warehouse. On one shelf of the now-exposed case was a scuffed leather milliner’s box containing Abraham Lincoln’s black stovepipe hat. On the shelf above it was a white plastic auction paddle, printed with the word CHRISTIE’S and the number 231. Beside it was a New York Post article mounted on a plaque, headlined “What a Corker!” and a yellowing piece of paper, mounted on a board, with a faded indigo scrawl. It was a letter from Thomas Jefferson to Joseph de Rayneval, a diplomat. Behind that, toward the wall, was a black Lucite cradle for displaying the bottle. Next to it, on a three-by-three-foot chocolate-colored piece of silver cloth, was the greenish-brown thing designated in the Forbes curatorial system as Object 85054: the Jefferson bottle. It rested on its side, stored as wine should be.

Since its purchase in 1985, the bottle had emerged from storage only occasionally—to be displayed in the Forbes Galleries, or to be photographed by Christie’s as a prop for wine accessories, or for Jefferson-related promotions. When the Jefferson Hotel in Washington, D.C., opened a new restaurant in 1990, the Forbeses lent the bottle to be displayed for two months.

Now Kirschstein gently retrieved it and brought it out of the room. On a round table, she spread out the cloth, and set the bottle upright on it. The front was clean, the back veiled with a clinging gauze of dust and grit. The black liquid within came only up to the shoulder, a dramatic difference from 1985, when the wine came within an inch and a half of the base of the cork. A black wax seal remained, but the cork, which eighteen years before had been bobbing in the liquid, was nowhere to be seen. If it was an eighteenth-century relic, it seemed out of place in the artificially bright, dun-carpeted offices.

Читать дальше