It wasn’t just drinking wine that interested Jefferson. True independence, he was sure, meant agricultural self-sufficiency. Americans would have to make their own wine if they didn’t want to rely on imports. Jefferson had first planted vines at Monticello in 1771, and a few years before his trip to Europe, he had encouraged an Italian immigrant named Filippo Mazzei to grow European wine-grape varieties by giving him 193 acres in Monticello’s backyard. Both efforts failed, but Jefferson remained hopeful for American wine.

Now, as his horse-drawn carriage clattered along the post roads of France, he at last had a chance to see the most fabled vineyards in the world. He traveled light, bringing only a single trunk with him. Wanting to experience the real France, unfiltered by preferential treatment and unburdened by diplomatic obligations, he traveled incognito, the plan being to hire a different valet in each town, so that no one would find out who he was.

Jefferson drank France in with guzzling intemperance. Aesthete and classicist, he basked in the scattered ruins of the Roman Empire. Social observer, he talked his way into people’s homes to see how they lived, ate their bread, and lay on their beds as if to rest but really to feel their softness. Farmer and wine aficionado, he moved from Burgundy to the Rhône Valley to Bordeaux; in each of these wine-growing areas, he closely studied the grapes grown, the composition of the soil, and the techniques of winemaking. He scrutinized the training of vines and the disparate blending methods. He obsessed over the production capacities of each château and the prices charged for each wine.

Jefferson was compulsively inquisitive, and he spoke French well enough to grill laborers and cellarmasters alike. How many years before a vine started to yield good fruit? Twenty-five. Did the winemakers dung their soil? A little. Did the vineyard overseer’s pay include board? No, just room and drink. Jefferson’s interest was more than pedantic; he was devouring all information that might help his young country to make its own wine.

At Aix-en-Provence, he luxuriated in the southern sun and soaked his aching wrist ten times a day in the spa town’s mineral-rich waters. At Agen, he ate the tiny thrushes called ortolans. For nine days, Jefferson left the road altogether, barging two hundred miles from the Mediterranean coast up the canal of Languedoc to Toulouse, serenaded by trees full of nightingales. He loved traveling this way, and divided his time between walking on the bank alongside the slow-moving boat and sitting in his coach, which rested wheelless atop the barge. Away from the crush of duty and unknown to those around him, he was able to relax and reflect—and perhaps get Maria Cosway out of his mind. During the entire 3,000-mile trip, he wouldn’t write a single letter to her.

Back on the road, he made the remaining journey to Bordeaux in three days. Along the way, he passed through rich farmland planted with corn, rye, and beans. As soon as he ferried west across the Garonne, just south of Bordeaux proper, the picture changed. On May 24, as he rolled through the district of Sauternes and entered Bordeaux, he looked out through the glass windows of his carriage and saw nothing but grapevines. An ocean away, the next day, the Constitutional Convention opened in Philadelphia.

In Bordeaux, Jefferson lingered. Though Burgundy’s reputation as a wine region was older, a combination of circumstances had led to Bordeaux’s greater fame abroad. Burgundy, being farther inland, had less access to export channels, and the complex ownership structure of the vineyards made the region hard to understand. The wine itself was unreliable; the region’s northern position meant more underripe vintages, and the fickleness of the thin-skinned pinot noir, the grape used to make Burgundy’s reds, only aggravated the problem.

Jefferson had told a colleague that he wanted to visit Bordeaux because it was one “of those seaports with which we trade.” The most important port in France, it served as the main staging area for trade with its West Indian colonies, a funnel for the bounty of southern France. But its role as a commercial hub was probably the least of the city’s attractions for Jefferson. Wine accounted for a full third of the cargo leaving Bordeaux, and some two-thirds of the region’s inhabitants were involved in some way in the business. Although in the course of his life Jefferson was a serial monogamist when it came to his favorite wines, regularly announcing some new one as supreme in his affections, his high esteem for Bordeaux would remain constant.

The place was booming. White stone mansions for the ascendant class of lawyers and merchants were going up in the commercial core; along its fringe the city was sprouting fresh streets. Bordeaux was now among the loveliest and most prosperous of European cities—with none of the wretched hunger and social turmoil rampant in other parts of France. Seven years before Jefferson arrived, Europe’s grandest new theater had been erected here, a neoclassical edifice fronted by a majestic portico with twelve soaring Corinthian columns.

Jefferson checked into the Hôtel de Richelieu in the city center and, over the next four days, divided his time between attending to business and being a tourist. A packet of letters and books, forwarded from Paris, awaited him here. Keeping up with correspondence was not, for Jefferson, simply a matter of putting pen to paper. He carried with him a portable copying press, and made duplicates of every letter he sent. In a separate journal he kept a record of every letter written and received. Now, writing with the special ink required to make copies, Jefferson spent a morning replying to correspondence. He also came to the aid of Thomas Barclay, the former American consul, who had recently traveled to North Africa to negotiate a peace with the Barbary pirates. Barclay had been released from debtor’s prison in Bordeaux a few days before, and Jefferson lent him 1,000 livres, fudging the expense to the United States as being “on acct. of [Mr. Barclay’s] Marocco [ sic ] mission.” Barclay was about to return to Paris, and Jefferson bet him a bottle of Burgundy that he would beat him there.

Not one to let nation-building get in the way of a little sightseeing, Jefferson visited the ruins of a third-century Roman arena and, given as he was to making constant comparisons, measured the height, width, and thickness of the bricks. He made a day trip southwest to Château Haut-Brion, in Graves, where the vines were just beginning their annual flowering. Haut-Brion was likely the only leading Bordeaux château Jefferson had time to visit.

On his third night in the city, Jefferson saw a play at the Grand Théâtre, which was only a few minutes’ walk from his hotel. The girls who danced and sang there, according to the city’s “scandalous chronicle,” were kept, at lofty salaries, by Bordeaux merchants. Jefferson enjoyed meals featuring the season’s produce of peas, cherries, and strawberries, and he admired the procession of elms along the Quai des Chartrons, an arcing strand that followed the curve of the Garonne River as it cut through the middle of the city.

The quay—ugly, muddy, stone-pocked, and only sporadically paved—was alive with the stir of commerce. It was the center of Bordeaux’s wine trade. Wagons drawn by cream-colored oxen wheeled past, and ocean-bound schooners heaped with barrels plied the broad waterway. The merchants had their offices here, and at the shore, barges took on and put off their quietly sloshing freight. Increasingly the wine was going to England, which had recently concluded a low-tariff trade pact with France, and where the upper and middle classes were developing a taste for better wines.

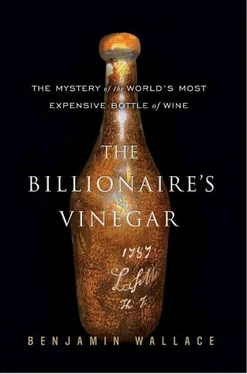

The first modern wine brands, with special status accorded to particular estates and vintages, were just then coming to prominence. The recent reinvention of the cork and the glass bottle, pioneered by the ancient Romans but long forgotten, had renewed the idea of deliberately aging wine. And the idea was now made practicable by the development of cylindrical bottles, which could be laid down horizontally, efficiently stacked en masse, and left to mature in the damp and darkness of a personal wine cellar. It was the finest wines, those with the greatest capacity to improve with age, that were set aside rather than consumed immediately. And the French wines that turned out to be best suited for aging were the reds of Bordeaux.

Читать дальше