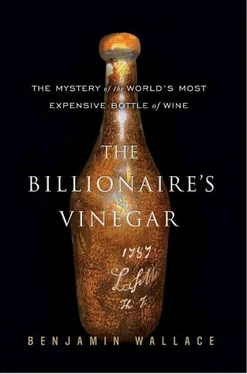

Trying to anticipate some of the objections that might be raised, Goodwin dealt with the possibility that Jefferson had received some bottles as a gift or as part of a trade. In order for a verbal, undocumented transaction of this sort to have taken place, it would need to have been before his departure from Paris in September 1789, which was, in those days of three or four years between harvest and shipping, early for the 1787 vintage.

Goodwin also allowed that there was a slim possibility that evidence of further orders would turn up (in 1985, Jefferson’s letters had only been published through 1791, and access to the unpublished letters was limited), but given the redundancy of Jefferson’s recordkeeping, and her access to both his letter log and his Memorandum Books, she thought it highly unlikely. She also acknowledged that a lack of documentary evidence did not definitively prove that the bottles weren’t Jefferson’s. Monticello had numerous relics it had deemed authentic without having a paper trail to back them up; in those cases, however, provenance had been supported by the objects’ uninterrupted passage through several generations of Jefferson’s descendants.

How the particular combination of châteaux and vintages announced by Rodenstock—some of which Jefferson had ordered and received in Paris, some of which he had ordered and expressly not received in Paris, some of which he had ordered and received in America, and some of which he seemed never to have ordered, but which, if he had ordered, would in any case have been after his return to America—had all ended up in Paris, and been engraved by the same hand, was beyond Goodwin, but in her report she hazarded a guess.

“Were there not Thomases, Theodores, or Theophiles, and Jacksons, Joneses, and Juliens who also had a taste for fine Bordeaux wine, and who would have been resident in Paris in 1790 or after, when the 1787 vintage would have been in bottles? I think it is a question of someone other than Jefferson, and perhaps there is an equally fascinating story there.” After making another perfunctory reference to the “honorable characters of Mr. Rodenstock and Mr. Broadbent,” she concluded that she could not “make the same leap of faith they have.”

WHEN GOODWIN’S REPORT came out, Broadbent and Rodenstock reacted not with gratitude that this servant of accuracy and historical truth had demolished their case for a Jefferson link, but with rage. Even the most detail-oriented person couldn’t be expected to “note every vintage and source of every bottle he ever purchased or received,” as one Broadbent/Rodenstock partisan wrote, especially someone as busy as Jefferson after his return to the United States.

Goodwin had made a convincing case, but Broadbent seized on three weaknesses in it. First, there was, as it turned out, a record of Jefferson having requested engraving of bottles. Shortly before leaving Paris in September of 1789, he had written to John Jay, America’s foreign secretary in New York, describing a shipment of wine to him and George Washington with diamond-engraved initials on each bottle. Second, Goodwin’s insistence about the form of the initials was a flimsy argument; there was no reason to assume that someone engraving the bottles for Jefferson would follow his exact and idiosyncratic mode of punctuation. Third, Goodwin had said that the only wine in the cache that Jefferson had recorded ordering was 1784 Yquem; she failed to connect Jefferson’s order of 1784 Margaux with the Rodenstock find. (She hadn’t caught this only because the early U.S. media reports about the cache hadn’t indicated that it included 1784 Margaux.)

These points made only glancing dents in Cinder Goodwin’s case, but they sufficed to give Rodenstock and Broadbent a basis to attack the entire report. “Cindy Goodwin,” as Broadbent called her, had been “led astray and raised doubts almost solely because of the initials on the bottle,” as had the New York Times ’s Howard Goldberg, whose probing questions Broadbent found distasteful. Goldberg was guilty, Broadbent wrote, of “the sort of investigative journalism we are all only too used to: like a terrier shaking a rabbit.” Rodenstock also supplied the VWGA Journal with a copy of what appeared to be a facsimile of an eighteenth-century page of Château d’Yquem’s ledger showing an explicit order by Jefferson for the 1787 vintage.

In a December 28 letter to Dan Jordan, Monticello’s new director, Rodenstock complained angrily that his integrity had been impugned by Goodwin. “[O]ne should courteously keep back one’s dubious and unfounded remarks,” Rodenstock wrote, “and one shouldn’t make oneself important in front of the press.” The controversy played out on the letters pages of Decanter . An elderly, impish Sussex winemaker named Arthur Woods, who frequently wrote letters to the editor dogging Broadbent, posed the rhetorical question, “Is it possible that Mr. Christopher Forbes, who bought the bottle, has not so much purchased a wine almost certainly undrinkable, or a genuine bottle of the period, worth perhaps £100, as a set of initials whose authenticity is likely to be vigorously challenged by those of a heretical bent?” He concluded by asking, “Did I hear somebody murmur ‘Piltdown Man’? Perish the thought.”

In Bordeaux, owners of the first-growth châteaux rallied behind Broadbent. Baron Eric de Rothschild, from Lafite, told Wine Spectator, “I don’t question its authenticity.” Comte Alexandre de Lur Saluces came next, attesting in Decanter to the authenticity of the Yquems that Rodenstock had found. Lur Saluces mentioned the letter in which Jefferson asked for bottles to be “labelled,” the original of which was in Yquem’s voluminous archives, and mentioned the 1784 order and “an order corresponding to 1787 as well” (Jefferson’s 1790 order in which he didn’t specify a vintage). It was the same evidence already weighed by Goodwin, but Lur Saluces put a different spin on it.

“I see no reason to doubt the authenticity of these bottles,” Lur Saluces continued. “Indeed, as far as the 1787 is concerned, we have been astonished at Yquem to discover an aroma that is familiar. After the tasting, the cellar master himself confirmed to me, that simply on the nose he had been able to recognize Yquem.” Lur Saluces called Rodenstock “my friend.” Broadbent himself wrote a letter to the editor that appeared in the July 1986 issue, in which he made the point: “I cannot imagine anyone in the late eighteenth century going to the trouble of engraving ‘Th.J,’ the name of the wine and the vintage, in the extraordinarily faint hope that in two hundred years’ time some susceptible collector would acquire it and some muggins of an American would pay an exorbitant price for it…. All I can repeatis that the bottle and its contents are amazingly right.”

Since neither side could prove anything, the dispute boiled down to where the burden of persuasion lay. Goodwin, a historian, made the case that it was very unlikely that the bottles were Jefferson’s. Surely it was statistically implausible that the only Jefferson bottles ever found intact would be the exact ones excluded from his extraordinarily thorough records (even if those records weren’t perfect, as evidenced by the unaccounted-for glass Lafite seal found in the dirt at Monticello). She contended that it was up to Broadbent and Rodenstock to convince the world otherwise. Meanwhile, Broadbent insisted that too many coincidences were involved for the bottles not to be Jefferson’s. His argument rested on several assumptions, not least of which was that no one had deliberately set out to fake the bottles.

FORTUNATELY FOR BROADBENT—and for Christie’s—Monticello didn’t come out with its report until a week after the auction had taken place. By then, the record price had vaulted the bottle high into the mediasphere, chronicled from Stockholm to Omaha to Melbourne. CBS News called it “the most famous bottle of wine in the world.” Most reports—whether in Newsweek , the AP, or the Times of London—stated unequivocally that it was Jefferson’s wine.

Читать дальше