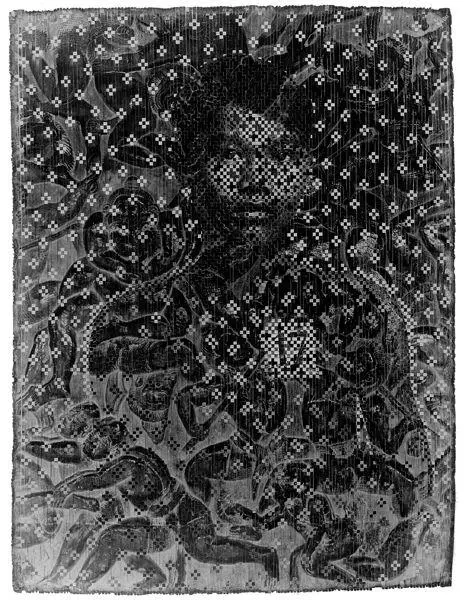

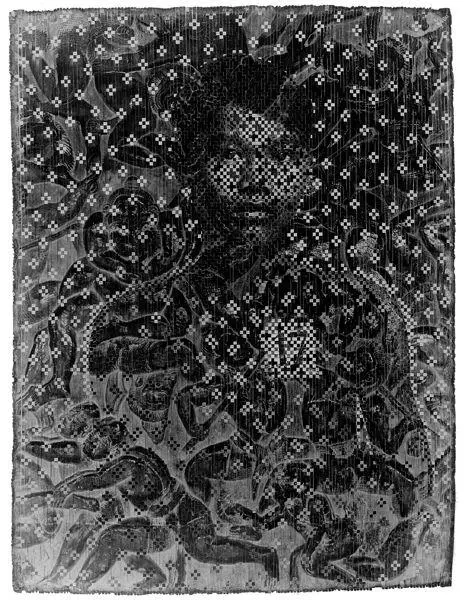

By turning the dead into a work of art, perhaps Lê runs the risk of being an accomplice, grave-robbing the dead and stealing their images. As Sontag points out, “the more remote or exotic the place, the more likely we are to have full frontal views of the dead and dying.” 20The living can take the images of the dead because they are strong and the dead are weak. In so doing, the living also may allow themselves to forget the ugliness of the dead’s passing, which is the danger of powerful memory done from the high ground. The benefit with such risk comes from the sense that the splendor of these lost lives cannot be terminated because of the way they died. Lê urges us to look at the dead again, past their victimization. 21Resurrected through art, the dead touch us, warning us against our latent inhumanity and telling us that the past can repeat if, paradoxically, we do not remember. This art also shows us, in the words of Toni Morrison, that “nothing ever dies,” an insight both terrifying and hopeful. 22

This is one of the ways that art resists the war machine. But the war machine finds ways to counter art, most seductively through rewarding it, particularly art of the cosmopolitan kind. Dinh Q. Lê and An-My Lê can both be characterized as cosmopolitan artists whose globally appealing work stands above and in stark contrast to the straightforward, even brutal art of the dead found in the Tuol Sleng museum. Cosmopolitan artists are valued by the people and the institutions in power, such as galleries, museums, festivals, foundations, and trade publishers with prestigious literary traditions. At the same time, cosmopolitan art, as well as cosmopolitan literature, may not do much to help the poor or exotic populations whom it speaks of and for. Given this vulnerability, can cosmopolitanism resist the war machine? Even if cosmopolitanism can cultivate within us a greater compassion for others and strangers, can it compel us to action in meaningful ways beyond the individual? Will cosmopolitanism and compassion lead us toward what Immanuel Kant calls “perpetual peace,” the antidote to perpetual war?

The skeptics say that cosmopolitanism imagines a world citizen who is impossible without a world state. If such a world state existed, it would be a totalitarian order, as no competing power will exist to check it. Cosmopolitanism also underestimates how many of us remain viscerally attached to our nations or cultures, which compel real love and passion in a way that cosmopolitanism does not. To some, cosmopolitans seem to be rootless people without loyalty, more inclined to love humanity in the abstract than people in the concrete. Dependent on a vision of the individual as a citizen of the world, particularly of the jet-setting, capitalist kind, cosmopolitanism may not be good at mobilizing masses of people, particularly the noncitizens such as refugees. At the same time, cosmopolitanism’s Western origins, arising from the Greeks, may mean it is unattractive to non-Western societies opposed to cosmopolitanism’s global ambitions and belief in individual rights and liberties. 23Cosmopolitanism may also be just as useful for war as for peace, as the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah implies. Echoing the claim of Levinas that justice requires a face-to-face dialogue, he endorses the cosmopolitan urge to converse with strangers, where conversation is “a metaphor for engagement with the experience and the ideas of others.” 24But “there are limits to cosmopolitan tolerance … we will not stop with conversation. Toleration requires a concept of the intolerable.” 25Appiah does not mention how tolerant cosmopolitans will deal with the intolerable, although scholar Paul Gilroy provides a name for this: “armored cosmopolitanism.” 26

As Levinas said, the face of the Other can elicit both justice and violence. The terrorist who does not want to talk with us tempts us to take up arms ourselves, even preemptively. Armored cosmopolitanism is the new spin on the white man’s burden, where the quaint idea of civilizing the world becomes retailored for culturally sensitive capitalists in the service of the United States, the World Trade Organization, and the International Monetary Fund. The idea and the imagination of being a citizen of the world, driven by compassion, may seem fairly anemic in a world dominated by such entities, to whom we could add the G8, the World Bank, Google, the Hollywood film industry, and so on, most of them staffed by fairly cosmopolitan people. This is why Elaine Scarry argues that we should not simply accept a “pleasurable feeling of cosmopolitan largesse” as the best measure for “imaginative consciousness.” Instead, such a consciousness must result in a “concrete willingness to change constitutions and laws.” 27

Still, because “the human capacity to injure other people is very great precisely because our capacity to imagine other people is very small,” Scarry says that imaginative works are important in expanding human consciousness. 28Without cosmopolitanism’s call for an unbounded empathy that extends to all, including others, we are left with a dangerously small circle of the near and the dear. Literature and art play an important role not only in expanding our compassion, but in circumscribing and compelling it, too. Our community exerts implicit and explicit pressure to empathize with our own, first by offering only stories about people like us. The absence of stories featuring others, or the presence of stories that render them as demons, stunts our moral imagination. We may not even think of others at all, or when we do we might wish them harm. And when we think of others generously, our community may penalize and threaten us, as happened to the novelist Barbara Kingsolver for what she wrote only days after 9/11. She mourned the victims but reminded her fellow Americans that bombings of that scale were hardly unusual and that Americans often carried them out. “Yes, it was the worst thing that’s happened, but only this week,” she wrote. “Surely, the whole world grieves for us right now. And surely it also hopes we might have learned, from the taste of our own blood … that no kind of bomb ever built will extinguish hatred.” 29

Kingsolver’s refusal to feel only for America’s own recalls Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech opposing the war in Vietnam:

here is the true meaning and value of compassion and nonviolence, when it helps us to see the enemy’s point of view, to hear his questions, to know his assessment of ourselves. For from his view we may indeed see the basic weaknesses of our own condition, and if we are mature, we may learn and grow and profit from the wisdom of the brothers who are called the opposition. 30

King labels the other not as a stranger or a foreigner but as the enemy, countering the sentimental inclination to say that we are all human. Acknowledging the other as the enemy, as the face of terror, as the inhuman, reminds us that the other is also not likely to see us from a generously compassionate point of view. Indeed, the other is also subject to low feelings, to the compulsory empathy demanded for and limited to the other’s own side. The other is as inhuman, and human, as we ourselves are. Appiah’s gesture at the intolerable shows how difficult it can be to achieve a conversation when two mutual enemies feel equally aggrieved, equally mired on the low ground, equally hateful of each other. While women, the colonized, and the minority can speak, their speech is often not heard by more powerful others unless it is on terms dictated by those others. Shut out from these conversations, or muted in them, these populations may resort to violence as a form of speech. Appiah calls this violence intolerant, and in some cases it is. But in other cases some may feel that violence is the only alternative when confronted by an unjust power that refuses to listen, to converse, and to change.

Читать дальше