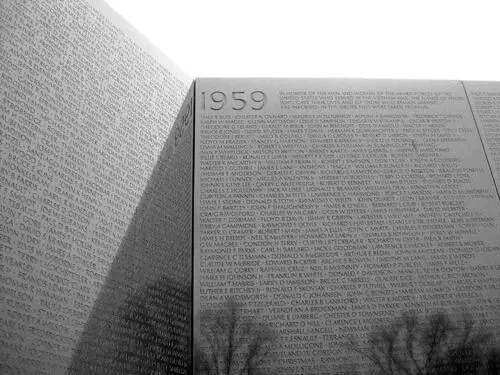

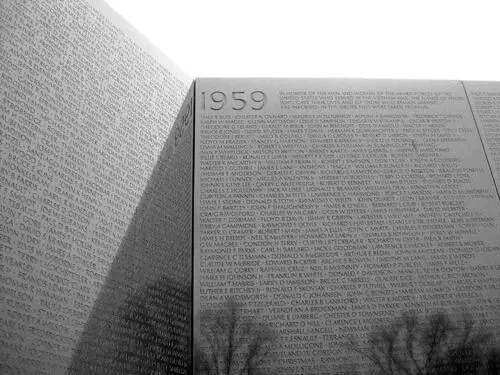

Through its design and its effect, the black wall reveals the porousness between the two ethical models of remembering one’s own and remembering others. In the crudest version of the ethics of remembering one’s own, we draw a clear line between us and them, the good and the bad, the here and the there, the living and the dead (for we will smite our enemies if they are not already dead). Such an ethics motivates people to fight wars against their enemies and draws from those “thick” relations of family, friends, and countrymen described by philosopher Avishai Margalit. Thick relations are apparently natural to Margalit, but in actuality these bonds must be made by us with people who are originally other to us. We solidify these bonds over time with the stories we tell ourselves about our love for our family, friends, and countrymen. The idea of family obscures this process of thickening because many people think of family bonds as natural, even though much evidence of alienation within family exists, from murder, abuse, violence and pedophilia to apathy, rivalry, and hatred. The biblical story of Cain and Abel tells us that it is as natural to kill those close to us as it is to love them, while Freud’s psychoanalytic story tells us that the gap between self and other begins within oneself soon after birth, at the mirror stage which Maya Lin’s reflective wall invokes. But despite this alienation from others and ourselves, the lucky among us discover that our family loves us, and we learn to love them in return. Gradually we extend the circle of the near and dear to those strangers who become our friends and neighbors, then our countrymen, until some of us learn the ultimate lesson, as Bao Ninh writes of Kien: “He would understand true sacrifice: friends who would die to save others.” 13But under the sway of patriotism and nationalism, we forget that we have learned how to remember these others, that our love is acquired rather than spontaneous.

The black wall and the controversies around it both illuminate and obscure how remembering one’s own and remembering others are always at play together. For many Americans, the black wall tells the story of how some among us were cast out, how they eventually came back, and how we welcomed them, at last restoring friendship, familial bonds, patriotic feelings, and good relations between citizen and soldier. Some of the controversies around the black wall arise, however, because some visitors feel that the black wall is not inclusive or reflective enough. This is the paradox of the ethics of remembering one’s own, that to be successful, it must convince the right others that they are recognized or should want to be recognized. This is also the problem of the mirror and the sight of memory: does the mirror reflect us, or the image of us that we would like to see? Does the mirror make us feel whole or does it make us feel like an other? Some veterans and their supporters did not see themselves reflected in the black wall’s memory; feeling themselves to be excluded, to be other, they demanded better representation. The visitor to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial thus encounters not only the black wall but also two sculptures nearby, one featuring black, white, and Latino GIs, weary and contemplative as they gaze at the wall, the other with three nurses tending to a wounded soldier. These sculpted soldiers and nurses are heroic, human, and embodied, commissioned by the memorial’s authorities to address the concern that the wall, without bodies and faces, could neither represent nor recognize the veterans. These sculptures also exist, then, to remember the nation’s own.

In order to do so, these sculptures require the nation to remember some of its historical others — minorities and women. Only a decade or two before the creation of the black wall, memorials, movies, or stories of American soldiers would not have featured minorities or women as the equals of white men, in the unlikely chance they were included at all. It would not be natural to include these others in a world where characters such as John Wayne or George Washington embodied the American soldier. In a society oriented around white men in power, women and minorities are what Margalit calls “strangers” 14and Paul Ricoeur calls “distant others.” 15And yet, thirty years after the black wall’s creation, what the sculptures show is that an American military without minorities is unthinkable. This narrative of an America made powerful through its diversity is embodied in America’s first black president, Barack Obama, who had this to say about the war:

The Vietnam War is a story of service members of different backgrounds, colors, and creeds who came together to complete a daunting mission. It is a story of Americans from every corner of our Nation who left the warmth of family to serve the country they loved. It is a story of patriots who braved the line of fire, who cast themselves into harm’s way to save a friend, who fought hour after hour, day after day to preserve the liberties we hold dear. 16

The recasting of this war as a heroic and patriotic endeavor is thus intertwined with optimism about reconciling the differences within American society and its military. In another thirty years, it is possible that an American military without women, or gays and lesbians, will be unthinkable, even if, for Margalit, these populations would today be strangers and distant others to many of “us.” For him, ethics covers the thick relations between the near and the dear, while morality governs the “thin” relations between “us” and our strangers and distant others. 17If Margalit indeed accepts this distinction between thick and thin as natural, the example of the memorial shows us that this distinction is not inevitable, but acquired. As people able to learn both love and hate, we expand our circle of the near and dear to include others, and formerly thin relations become thicker.

Rather than think of “our” relationship to others as a thin one existing in a moral realm, influenced by religious codes, I think of this relationship as existing in an ethical realm where people can struggle to remember others through secular acts of inclusion, conversation, recognition, and hope. The remoteness of these strangers and distant others is not only a function of geography, as Margalit implies. Sometimes we detest our neighbors and feel more affinity for those far away, as is the case with some Americans’ attitudes toward Mexico and, say, England. Those who feel such affinity believe it to be natural, even though it is actually learned. The naturalness arises from our having forgotten how we came by this affinity whereby some Americans think that they share more culturally with the English than the Mexicans. In contrast to psychic intimacy, physical proximity is not a guarantee of creating feelings of nearness and dearness. Americans did not enslave those who lived far from them, but instead enslaved those who lived with them or next door to them, including their lovers and illegitimate offspring. Men denied the vote to their wives and daughters and constricted their lives. Today, of course, slavery and the denial of political franchise to vast populations no longer seem to exist as realistic options. But there is nothing “natural” about this current state of fragile, partial reconciliation around race and gender relations. Bitter political struggle led Americans to this point. This struggle included a multitude of intimate gestures and relationships between people who chose to learn about and live with others, even to love them. The moral demand to treat our fellow human beings as we wish to be treated becomes, through political effort, the ethics of seeing them as part of our “natural” community, sharers of our national identity.

Читать дальше