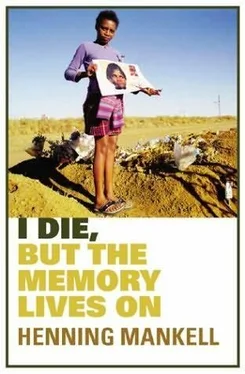

Henning Mankell - I Die, but the Memory Lives on

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Henning Mankell - I Die, but the Memory Lives on» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:I Die, but the Memory Lives on

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

I Die, but the Memory Lives on: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «I Die, but the Memory Lives on»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A powerful, moving and tragic account of the families shattered and children orphaned as a result of the spread of HIV and, through the Memory Books project, a hope for the future.

Henning Mankell is best known for his highly successful crime novels, but few people are aware of his work with Aids charities in Africa and how he actively promotes and encourages the writing of memory books throughout the country. Memory Books is a project through which the HIV-infected parents of today are encouraged to write portraits of their lives and testaments of their love for their orphans of tomorrow. Through a combination of words and drawings they can leave a legacy, a hope that future generations may not suffer the same heartbreaking fate.

In I Die, but the Memory Lives on, this master storyteller has written a fable to illustrate the importance of books as a means of education, of preserving memories and of sharing life. In a very personal account he tells of his own fears and anxieties for the sufferers of HIV and Aids and, drawing on his experiences in many parts of Africa, proposes a way to help. This fable, The Mango Plant, comprises most of the book and is followed by factual afterwords from Dr Rachel Baggaley (Head of the Christian Aid HIV Unit) and Anders Wijkman (Member of the European Parliament, formerly Assistant Secretary General of the UN, and board member of Plan Sweden), and ends with a template for a memory book as an appendix.

The problem of Aids has been kept largely under control in Europe and is not therefore an issue at the forefront of our minds, but in the Third World it is a very different story. Lack of education about the disease and lack of money to buy life-prolonging drugs for existing sufferers have turned the problem into a plague of biblical proportions. 30 million people are HIV positive in Africa, almost 39 percent of the adult population in countries such as Botswana. In Zimbabwe life expectancy has now sunk to below 40 years of age, by 2010 it is predicted to fall to 30 years. As thousands die in their prime, there begins a shortage of teachers, labourers, and essential personnel that enable a country to run efficiently, not to mention the 14 million children that have been orphaned by HIV/Aids since the 1980s. These children are taken out of school in order to care for the sick and elderly. A lack of education and continued poverty perpetuates the problem.

Because levels of literacy are so low, the memory books also contain photographs (Mankell campaigns for cheap disposable cameras) and anything else that will evoke a memory, whether it be a drawing, a crushed flower or a lock of hair, anything that the orphan will relate to and inspire them to try the best they can to create a future.

Henning Mankell was first introduced to the Memory Book Project by Plan, a child-focused international development organisation, who had established the scheme in Uganda. UNAIDS estimate 1 million people in Uganda are infected with the disease and 200,000 have died from Aids-related illnesses. Since the outbreak in 1978, it is estimated 1.2 million children have been orphaned in Uganda alone. Plan Uganda encourages parents with the disease to create a memory book about their family history, matters of death, separation and sexuality for the child or children they will leave behind.

There are numerous worldwide charities and organisations working to fight the spread of HIV/Aids – further information and contact details can be found at the end of I Die, but the Memory Lives on.

Henning Mankell has kindly agreed to donate the royalties from I Die, but the Memory Lives on to an Aids charity of his choice.

The publication of I Die, but the Memory Lives on will raise awareness of this international problem, which, though it may not always be on the front pages of our newspapers, must always be on our minds until something has truly changed for the better.