Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: University of California Press, Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

- Автор:

- Издательство:University of California Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:9780585335100

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Page 5

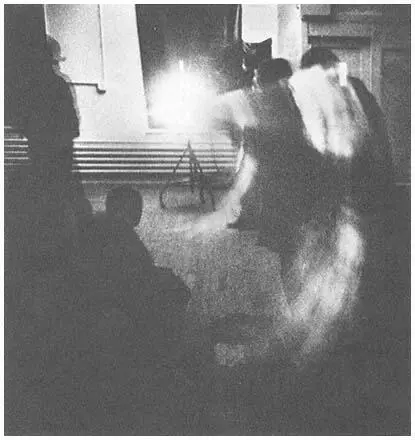

The audience investigates the projector beam during McCall's

Line Describing a Cone

(1973).

In general, the interviews collected here provide a chronological overview of independent filmmaking since 1950, especially in North America. The first three intervieweesRobert Breer, Michael Snow, Jonas Mekasmdiscuss developments from the early fifties and conclude in the late seventies (Mekas), the early eighties (Breer), and 1990 (Snow). The next two intervieweesBruce Baillie, Yoko Onoreview developments beginning in the late fifties (Baillie) and early sixties (Ono). Anthony McCall and Andrew Noren discuss their emergence as filmmakers in the early seventies and the mid sixties, respectively. The Anne Robertson and James Benning interviews begin in the mid seventies and end very recently. And so on.

Page 6

Another historical trajectory implicit in the order of the eighteen interviews has to do with the types of critique developed from one decade to the next. Of course, the complexity of the history of North American independent cinema makes any simple chronology of ap- proaches impossible. Indeed, each decade of independent film production has been characterized by the simultaneous development of widely varying forms of critique. And yet, having said this, I would also argue that certain general changes in focus are discernible. One of these is the increasingly explicit political engagement of filmmakers. The films of Breer and Snow emphasize fundamental issues of perception, especially film perception. From time to time, one of their,' films reveals evidence of the filmmaker's awareness of the larger social/political developments of which their work is inevitably a part, but 'in general they focus on the cinematic worlds 'created by their films. The focus of the films of Mekas, Baillie, Ono, and McCall is broader: the worlds

in

'their films are some, What more directly engaged with social/political developments outside their work. In several of Mekas's major films, for example, the filmmaker's real homeland (Lithuania) is ultimately "replaced" by the creation of an "aesthetic homeland" that, exists within themselves and Within the social and institutional world documented by the films. Mekas may ''really lave only in my editing room" but his life there is, as his films make clear contextualized by the personal/ethnic/political history out of which this current "real life" developed.

With few exceptions, the remaining interviews in Volume 2 reveal a growing interest in national and global concerns. Some interviewees-Benning, for example, and Ross McElwee and Su Friedrich-makes films that reveal in some detail how their personal lives are affected by larger social and political developments; Friedrich, in particular, uses the process of filmmaking as a means of responding to these developments. Severson, Mulvey, Yvonne Rainer, and Trinh T. Minh-ha have used filmmaking to explore the gender politics that underlie contemporary life and thus inform much of the popular cinema, and Trinh and Rainer in particular relate the disenfranchisement implicit in these gender politics to other forms of disenfranchisement: to the undervaluing of ethnic heritages within the United States and of the cultural practices of "Third World" peoples. Godfrey Reggio and Peter Watkins explore the possibility of a global cinematic perspective, in films that attempt to demonstrate the interconnectedness of all cultures and their parallel problems and aspirations.

The other general organizational principle that informs

A Critical Cinema 2

is my arrangement of the interviews so that each successive pair of interviews (the mini-interviews with Severson, Mulvey, and Rainer are treated as a single piece) reveals a general type of response to

Page 7

the conventional cinema

and

articulates a set of similarities and differences between the work of the paired filmmakers. My hope is that the implicit double-leveled interplay will make clear that the contributions of the filmmakers interviewed are not a series of isolated critiques of the conventional film experience but are parts of an explicit and/or implicit discourse about the nature of cinema. For those interested in teaching or programming a broader range of film practice, a brief review of the implications of a few of my pairings might make the complex and simulating nature of this discourse more apparent.

Breer and Snow came to filmmaking from the fine arts, having already established themselves as painters and sculptors (Snow was also a musician). Neither uses filmmaking as a means of developing narratives peopled by characters with whom viewers do and don't identify. There are, at most, references to conventional narrative and character development in their filmsin some instances, just reference enough to make clear that the conventions are being defied. The focus of Breer's and Snow's films is the nature of human perception. Breer's animations continually toy with our way of making sense of moving lines and shapes. At one moment, we see a two-dimensional abstraction, and a moment later a shift of a line or a shape will suddenly transform this abstraction into a portion of a representational scene that disappears almost as soon as we grasp it. In

Wavelength

(1967) and

Back and Forth

[

«

] (1969), Snow sets up systematic procedures that allow him to reveal that certain types of events, or filmstocks, or camera speeds cause the same filmed spaces to flatten or deepen, to be seen as abstract or representational. Both filmmakers confront the conventional viewer's expectations with considerable wit and frequent good humor.

But while Breer and Snow critique some of the same viewer assumptions in some of the same general ways, their films are also very different. Nearly all of Breer's films are brief animations of drawings and still photographs. Indeed, Breer is a central figure in the tradition of experimental animation, which has functioned as an alternative to the commercial cartoon and its replication of the live-action commercial cinema. With the exception of his first film, Snow has made live-action films, some of them very long. While Breer's films move so quickly as to continually befuddle us, Snow's films often move so slowly as to challenge our patience. Both filmmakers confront our expectations about what can happen in a certain amount of film time, but they do so in nearly opposite ways.

The second pair of interviewees mount a very different kind of critique of conventional cinema. Mekas was a poet before coming to the United States after World War II, and once he arrived here, he trans-

Page 8

posed his free-form approach to written verse into a visually poetic film style (a style that often includes written text). Baillie, too, came to see himself as a visual poet, translating traditional literary stories and rituals (the legend of the Holy Grail, the Catholic Mass,

Don Quixote

) into new, cinematic forms. Both filmmakers were, and remain, appalled by the conformist tendencies of American society, by what they see as the denigration of the spiritual in popular culture, and by the more militaristic dimensions of modern technologytendencies so often reflected in the popular cinema. Both have produced a body of films that sing the nobility of the individual, of the simple beauties of the natural world, and of peaceful forms of human interaction. And both have embodied their personal ideologies in institutions (Mekas: the New York Cinematheque, the New York Film-makers' Cooperative,

Film Culture,

Anthology Film Archives; Baillie: Canyon Cinema) that have attempted to maintain the presence of alternative cinema in a nation dominated by the commercial movie and television industries.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.