Douglas Hofstadter - I Am a Strange Loop

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Douglas Hofstadter - I Am a Strange Loop» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:I Am a Strange Loop

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

I Am a Strange Loop: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «I Am a Strange Loop»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

I Am a Strange Loop — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «I Am a Strange Loop», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

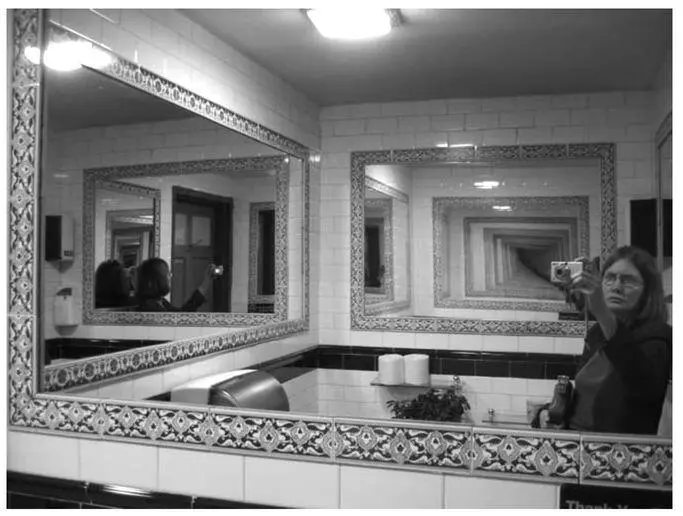

Also, I had always loved standing between two mirrors and seeing the implied infinitude of images as they faded off into the distance. (The photo was taken by Kellie Gutman.) A mirror mirroring a mirror — what idea could be more provocative? And I loved the picture of the Morton Salt girl holding a box of Morton Salt, with herself drawn on it, holding the box, and on and on, by implication, in ever-tinier copies, without any end, ever.

Years later, when I took my children to Holland and we visited the park called “Madurodam” (those quote marks, by the way, are a testimony to the lifelong effect on me of Nagel and Newman’s insistence on the importance of distinguishing between use and mention), which contains dozens of beautifully constructed miniature replicas of famous buildings from all over Holland, I was most disappointed to see that there was no miniature replica of Madurodam itself, containing, of course, a yet tinier replica, and so on… I was particularly surprised that this lacuna existed in Holland, of all places — not only the native land of M. C. Escher, but also the home of Droste’s famous hot chocolate, whose box, much like the Morton’s Salt box, implicated itself in an infinite regress, something that all Dutch people grow up knowing very well.

The roots of my fascination with such loops go very far back. When I was but a tyke, around four or five years old, I figured out, or was told, that two twos made four. This catchy phrase — “two twos” — sent thrills up and down my spine, because I realized that it involved applying the notion of “two” to itself. It was a kind of self-referential operation, the twisting-back of a concept on itself. Just like a daredevil pilot or rock-climber, I craved more such experiences and riskier ones as well, so I quite naturally asked myself what three threes made. Being too small to figure this mystery out for myself (by making a square with three rows of three dots each, for instance), I asked my mother, that Font of Wisdom, for the answer, and she calmly informed me that it was nine.

At first I was delighted, but it didn’t take long before vague worries started setting in that I hadn’t asked her the right question. I was troubled that both my new phrase and the old phrase contained only two copies of the number in question, whereas my goal had been to transcend twoness. So I pushed my luck and invented the more threeful phrase “three three threes” — but unfortunately, I didn’t know what I meant by it. And so I naturally turned once again to the All-Wise One for help. I remember we had a conversation about this matter (which, at that tender age, I was convinced was surely beyond the grasp of anyone on earth), and I remember she assured me that she fully understood my idea, and she even told me the answer, but I’ve forgotten what it was — surely 9 or 27.

But the answer is not the point. The point is that among my earliest memories is a relishing of loopy structures, of self-applied operations, of circularity, of paradoxical acts, of implied infinities. This, for me, was the cat’s meow and the bee’s knees rolled into one.

The Timid Theory of Types

The foregoing vignette reveals a personality trait that I share with many people, but by no means with everyone. I first encountered this split in people’s instincts when I read about Bertrand Russell’s invention of the so-called “theory of types” in Principia Mathematica, his famous magnum opus written jointly with his former professor Alfred North Whitehead, which was published in the years 1910–1913.

Some years earlier, Russell had been struggling to ground mathematics in the theory of sets, which he was convinced constituted the deepest bedrock of human thought, but just when he thought he was within sight of his goal, he unexpectedly discovered a terrible loophole in set theory. This loophole (the word fits perfectly here) was based on the notion of “the set of all sets that don’t contain themselves”, a notion that was legitimate in set theory, but that turned out to be deeply self-contradictory. In order to convey the fatal nature of his discovery to a wide audience, Russell made it more vivid by translating it into the analogous notion of the hypothetical village barber “who shaves all those in the village who don’t shave themselves”. The stipulation of such a barber’s existence is paradoxical, and for exactly the same reason.

When set theory turned out to allow self-contradictory entities like this, Russell’s dream of solidly grounding mathematics came crashing down on him. This trauma instilled in him a terror of theories that permitted loops of self-containment or of self-reference, since he attributed the intellectual devastation he had experienced to loopiness and to loopiness alone.

In trying to recover, then, Russell, working with his old mentor and new colleague Whitehead, invented a novel kind of set theory in which a definition of a set could never invoke that set, and moreover, in which a strict linguistic hierarchy was set up, rigidly preventing any sentence from referring to itself. In Principia Mathematica, there was to be no twisting-back of sets on themselves, no turning-back of language upon itself. If some formal language had a word like “word”, that word could not refer to or apply to itself, but only to entities on the levels below itself.

When I read about this “theory of types”, it struck me as a pathological retreat from common sense, as well as from the fascination of loops. What on earth could be wrong with the word “word” being a member of the category “word”? What could be wrong with such innocent sentences as “I started writing this book in a picturesque village in the Italian Dolomites”, “The main typeface in this chapter is Baskerville”, or “This carton is made of recyclable cardboard”? Do such declarations put anyone or anything in danger? I can’t see how.

What about “This sentence contains eleven syllables” or “The last word in this sentence is a four-letter noun”? They are both very easy to understand, they are clearly true, and certainly they are not paradoxical. Even silly sentences such as “The ninth word in this sentence contains ten letters” or “The tenth word in this sentence contains nine letters” are no more problematical than the sentence “Two plus two equals five”. All three are false or at worst meaningless assertions (the second one refers to something that doesn’t exist), but there is nothing paradoxical about any of them. Categorically banishing all loops of reference struck me as such a paranoid maneuver that I was disappointed for a lifetime with the oncebitten twice-shy mind of Bertrand Russell.

Intellectuals Who Dread Feedback Loops

Many years thereafter, when I was writing a monthly column called “Metamagical Themas” for Scientific American magazine, I devoted a couple of my pieces to the topic of self-reference in language, and in them I featured a cornucopia of sentences invented by myself, a few friends, and quite a few readers, including some remarkable and provocative flights of fancy, such as these:

If the meanings of “true” and “false” were switched, this sentence wouldn’t be false.

I am going two-level with you.

The following sentence is totally identical with this one, except that the words “following” and “preceding” have been exchanged, as have the words “except” and “in”, and the phrases “identical with” and “different from”.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «I Am a Strange Loop»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «I Am a Strange Loop» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «I Am a Strange Loop» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.