Babies are born with brains 25 percent of adult size, because the mechanics of walking upright impose a constraint on the size of the mother’s pelvis; the channel through which the baby is born can’t get any bigger. The baby’s brain quickly makes up for that initial constraint: by age 1, the brain is 75 percent of adult size.

Infants have accurate hearing up to 40,000 cycles per second and may wince at a dog whistle that adults, who can’t register sounds above 20,000 cycles per second, don’t even notice. Your ears contain sensory hair cells, which turn mechanical fluid energy inside the cochlea into electrical signals that can be picked up by nerve cells; these electrical signals are delivered to the brain and allow you to hear. Beginning at puberty, these hair cells begin to disappear, decreasing your ability to hear specific frequencies; higher tones are the first to go.

A newborn’s hands tend to be held closed, but if the area between the thumb and forefinger is stroked, the hand clenches it and holds on with sufficient strength to support the baby’s weight if both hands are grasping. This innate “grasp reflex” serves no purpose in the human infant but was crucial in the last prehuman phase of evolution when the infant had to cling to its mother’s hair.

My father reminds me that according to Midrash—the ever-evolving commentary upon the Hebrew scriptures—when you arrive in the world as a baby, your hands are clenched, as though to say, “Everything is mine. I will inherit it all.” When you depart from the world, your hands are open, as though to say, “I have acquired nothing from the world.”

If a baby is dropped, an immediate change from the usual curled posture occurs, as all four extremities are flung out in extension. The “startle reflex,” or “embrace reflex,” probably once served to help a simian mother catch a falling infant by causing it to spread out as fully as possible.

When Natalie was born, I cried, and my wife, Laurie, didn’t—too busy. One minute, we were in the hospital room, holding hands and reading magazines, and the next, Laurie looked at me, with a commanding seriousness I’d never seen in her before, and said, “Put down the magazine.” Natalie emerged, smacking her lips, and I asked the nurse to reassure me that this didn’t indicate diabetes (I’d been reading too many parent-to-be manuals). I vowed I would never again think a trivial or stupid or selfish thought; this exalted state didn’t last, but still…

The Kogi Indians believe that when an infant begins life, it knows only three things: mother, night, and water.

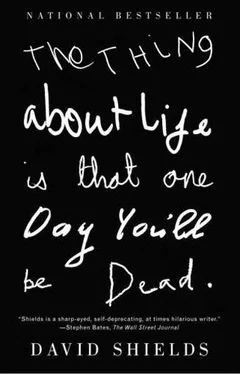

Francis Thompson wrote, “For we are born in other’s pain, / And perish in our own.” Edward Young wrote, “Our birth is nothing but our death begun.” Francis Bacon: “What then remains, but that we still should cry / Not to be born, or being born, to die?” The first sentence of Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory is: “The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.”

Much mentioned but rarely discussed: the tissue-thin separation between existence and non-. In 1919, at age 9, my father and his friends were crossing train tracks in Brooklyn when my father, last in line, stepped directly on the third rail, which transformed him from a happy vertical child into a horizontal conductor of electric current. The train came rattling down the tracks toward Milton Shildcrout, who, lying flat on his back, was powerless to prevent his own self-induced electrocution. (When I asked my father why he changed his name, he said that his WWII sergeant “had trouble reading words of more than two syllables printed in the daily camp bulletin; he also had trouble correctly pronouncing what he described as ‘those god-awful New Yawk names.’ He said, in his thick-as-molasses Southern accent, ‘That name of yours, Corporal, is so danged long it wouldn’t fit on a tombstone just in case ya step on one of Tojo’s bullets when we go overseas. You should shorten it to something a grown man like me can pronounce. From now on, I’m going to call you Shieldsy.’ A few weeks later, Sergeant Hill shortened it to Shields. And Shields it was for the 36 months I was assigned to the 164th Quartermaster Company. I got used to Shields and, when I returned from the war, had it changed.”)

I wouldn’t be here today, typing this sentence, if someone named Big Abe, a 17-year-old wrestler who wore black shirts and a purple hat, hadn’t slid a long piece of dry wood between galvanized little Milt and the third rail, flipping him high into the air only seconds before the train passed. My father was bruised about the elbows and knees and, later in summer, was a near-corpse as flesh turned red, turned pink, turned black, and peeled away to lean white bone. Toenails and fingernails crumbled, and what few hairs he had on his body were shed until Miltie himself had nearly vanished. His father sued Long Island Rail Road for $100, which supposedly paid—no more, no less—for the doctor’s visits once a week to check for infection.

All mammals age; the only animals that don’t age are some of the more primitive ones: sharks, alligators, Galapagos tortoises. There are different theories as to why humans age at the rate they do: aging is genetically controlled (maladapted individuals die out and well-adapted ones persevere); the rate of aging within each species has developed for the good of each species; an entropy-producing agent disrupts cells; smaller mammals tend to have high metabolic rates and die at an earlier age than larger mammals do; specific endocrine or immune systems are particularly vulnerable and accelerate dysfunction for the whole organism; errors in DNA transcription lead to genetic errors that accelerate death. All of these theories are disputed: no one knows why we age.

Schopenhauer said, “Just as we know our walking to be only a constantly prevented falling, so is the life of our body only a constantly prevented dying, an ever-deferred death.” (Dad: “Why would a supposedly wise man want to think this way?”)

“As we get older,” the British poet Henry Reed helpfully observed, “we do not get any younger.”

On average, infants sleep 20 hours a day, 1-year-olds sleep 13 hours a day, teenagers sleep 9 hours, 40-year-olds sleep 7 hours, 50-year-olds sleep 6 hours, and people 65 and older sleep 5 hours. As you get older, you spend more time lying awake at night and, once asleep, you’re much more easily aroused. The production of melatonin, which regulates the sleep cycle, is reduced with age, which is one of the reasons why older people experience more insomnia. By age 65, an unbroken night of sleep is rare; 20 percent of the night consists of lying awake. As I constantly have to remind my now light-sleeping father, people ages 73 to 92 awake, on average, 21 times a night owing to disordered breathing.

An infant breathes 40 to 60 times a minute; a 5-year-old, 24 to 26 times; an adolescent, 20 to 22 times; an adult (beginning at age 25), 16 times. Over the course of your life, you’re likely to take about 850 million breaths.

As a mammal, you get “milk teeth” by the end of your first year, then a second set that emerges as you leave infancy. When children start school, most of them have all of their baby teeth, which they’ll lose before they’re 12. By 13, most children have acquired all of their permanent teeth except their wisdom teeth. The third molars, or “wisdom teeth,” usually emerge between ages 20 and 21; their roots mature between ages 18 and 25. As you age, your plaque builds up, your gums retreat, your teeth wear down, and you have more cavities and periodontal disease. The last few years, as my father’s gums have shrunk, bone has rubbed up against his dentures, causing pain whenever he chews.

Читать дальше