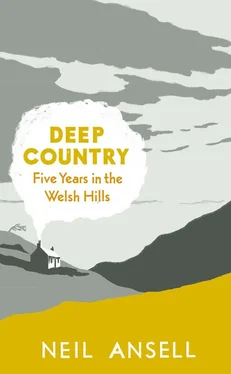

Neil Ansell - Deep Country

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Neil Ansell - Deep Country» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Hamish Hamilton, Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Deep Country

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hamish Hamilton

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-0-141-96133-0

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Deep Country: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Deep Country»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

His dilapidated cottage, rented for £100 per year, is so exposed to the elements that it appears to rain uphill, and so remote that you can walk for twenty miles west without seeing a single other dwelling. As the years pass he feels himself dissolving into, and becoming, just another part of the landscape.

Deep Country — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Deep Country», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Just past the bridge was a fine beach with a swimming hole, and I would often pause here for a while if the weather was good. In spite of its proximity to the village there was almost never anyone else here. As I stepped into the water thousands of tiny fish would dart away from the shallows, and before long there would be a loud chikeee and a lightning bolt in neon blue would flash past. The kingfishers nested in the bank here every year without fail, even though the village boys would sometimes stopper their holes with stones as a game. It was a good place to bring guests; even people with no real interest in birds like to see a kingfisher — they are just so glamorous and unexpectedly tiny, and the sighting was almost guaranteed.

After loading up with supplies, I would need to make a decision; whether to retrace my steps along the riverbank or walk back along the lanes. Almost anyone who lived along these lanes and who passed by would stop and give me a lift, but there were not many of them, and I could easily find myself walking the whole way back without a car passing. And it was a lot further. About a quarter of the way home from the village was my local telephone box, but I wouldn’t stop. This would be a separate trip, on a Sunday when people would not be at work, but of course then the shop would not be open either.

I remember once walking to the village shop, collecting up my few basic requirements and taking them up to the counter, and as I spoke to the shopkeeper my voice cracked. It was only then that I realized I hadn’t spoken a word in at least two weeks. It also made me aware that I never talked to myself, never sang to myself, not ever.

Going down to cross the river one day after I had already been at the cottage a year or two, I came upon a team of men renovating the old footbridge. It was probably not before time; I was used to it, but my visitors would sometimes be alarmed by how it swayed and rocked. If you walked fast, it would roll like a wave under your feet, and the suspension would creak and groan. And it was a long way down to the rocky waters below. I got chatting to the foreman of the gang, and found that his family was the last to live at Penlan. He had lived there until he was seven, when the family had decanted to town. He asked me if I snared many rabbits up there, and I said none at all, as I was vegetarian. Then he asked the route I followed into the village, and was delighted to discover that my chosen path was almost identical to his daily walk to the village school. The railway bridge was still standing then, which would have cut out that final dog-leg, and reduced the journey time a little, but even so it was an astonishing distance for a five-year-old to cover twice a day. And he had to be there at seven o’clock sharp, or face the consequences. I asked him if he could conceive of living that life now, and he said absolutely, he loved it, except … except for one thing. He could not imagine life without a television.

Less often I travelled into town, which had a health-food shop where I could stock up on dried pulses for my one-pot stews and fine-ground flour for the unleavened bread I made on a griddle over the fire. There was a hardware store for paraffin for my lamps and seeds for the garden, and a library. Occasionally I would take the daily postbus, but usually I hitchhiked. These were not busy roads, but I got lifts from regulars. The Travellers from a nearby site would stop for me without fail, as did a retired man who lived up-valley opposite the quarry. He would always tell me when the peregrines had returned to their eyrie. He’d spent his entire working life researching foxes for the Ministry of Agriculture, and was now spending his entire retirement travelling to and from the nearest golf course. In view of his wealth of experience, I asked him his opinion on whether or not foxes are pests. After some consideration he said: No, foxes are not pests, the foxes were here first. People are pests.

It was not a large garden. I say garden, but perhaps I should say the area around the cottage enclosed by a fence, for it had few attributes to distinguish it from the fields across that fence, although in February there would be a drift of snowdrops under my fruit tree, soon to be followed first by crocuses and then by huge numbers of daffodils. Long ago, someone had planted a scattering of bulbs, and over the years they had divided and divided so that each bulb became a cluster, and now in March the cottage would be surrounded by hundreds of nodding golden heads. Without the sheep coming in to trim it, the grass grew in rank tussocks that I had to hack back with a sickle. Besides the fruit tree, the jackdaw ash and the cotoneaster next to the porch, there was one small rhododendron and a clump of blackthorn by the gate. Once, before my time, a solitary pine had stood guard over the house from above the quarry wall, but it had been unlucky. The landlords, fearing that the ash balanced on the rocks would come crashing down on the cottage roof, had sent up a man to fell it, and he had mistakenly taken out the pine instead. The ash lived on to teeter another day, and teeters still, twenty years later. All that remains of the pine is its stump, a favoured perch for the green woodpeckers when they visit. I planted out a larch to stand in for the lonesome pine, and in the south-west corner of the garden a beech, which will one day afford the cottage a little shelter from the prevailing wind. Then a couple of rowans, for berries for the birds, and a buddleia for the butterflies. Apart from a row of poppies and wild flowers along the fence, I didn’t trouble with flowers. I needed the land for food.

Although I planted a patch of herbs — coriander, dill and parsley, which were unavailable locally — my priority was the heavy vegetables. I didn’t want to be hauling sackfuls of potatoes up the mountainside when I could be growing them myself. Preparing the land was hard work; the roots of the grass grew deep and tangled. Then I had to pick out all the rocks, carefully lift any daffodil bulbs for transplant-ation elsewhere, and lime the soil. Each year I would dig an extra patch, and prepare another for the next year by pegging down a sheet of tarpaulin with bricks to kill off the grass. I didn’t want to use any pesticides, and besides the lime I bought no fertilizer. Each winter, when the bats were long gone to their hibernation roost, I would clamber up into the loft and shovel up bagfuls of guano. It was dry and powdery and odourless, and it seemed somehow appropriate that the bats who shared my home with me should help me grow my food.

I had never grown anything before, I had never stayed in one place long enough to even think about it, and had no idea what would grow well at this altitude, and in a location so exposed to the elements, so it was a process of trial and error. Each year I would try a few new things; if they grew well they would become a fixture; if they failed I would abandon them and try something else. I had a small patch of early potatoes, and a larger patch of main crops. I got a metal dustbin which I kept in the pantry and would fill it to the top with these, enough to last the whole year. Onions and garlic I hung on strings on the woodshed wall, as the mice didn’t ever bother them. Garlic was the only thing I planted in autumn; growing garlic seems magical in its simplicity. Take a head of garlic, break it into cloves and plant them in a row. By the next year each clove will have turned into a new head.

Carrots and parsnips I stored in the ground and lifted when I needed them. The carrots in particular were a revelation; they are hard to grow in most places because of the depredations of the carrot fly, but the altitude here kept my crop pest-free. They grew to over a pound in weight without becoming woody, were such a deep orange they were almost red, and tasted better than any others I have had before or since. My first year I grew a fine crop of broad beans, but the next year and the one after they were infested by blackfly just as the pods were beginning to swell. The blackfly brought a fungal infection that wiped out the entire crop, so reluctantly I had to give up on them. My biggest problem was finding the right green vegetable. I could pick wild greens in season — sorrel and nettle tops, occasionally watercress from the mountain streams — but I needed something that I could rely on. Cabbages were destroyed by flea beetles, and though I managed a small crop of kale it was riddled with holes. Spinach was too inclined to bolt and had a short season. Then I found spinach beet, untroubled by pests and hardy enough to survive the worst of the winter’s frosts. I could dust away the snow and pluck the fresh leaves below, so I had a supply of greens year-round. But if there is a satisfaction to be had from selecting and picking food you have grown yourself as and when it is time to eat, I found far more pleasure in foraging for wild food. Perhaps I am more in touch with my inner hunter-gatherer than my inner pastoralist.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Deep Country»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Deep Country» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Deep Country» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.